Ordinarily, trekking into high alpine zones requires days or even weeks of altitude acclimatization to help you adjust to the fewer oxygen particles you'll be taking in each breath. Weird things happen to your body and without acclimatizing, hikers and mountaineers can easily fall foul to symptoms of debilitating altitude sickness – headache, nausea, dizziness and insomnia among them.

According to CDC recommendations, at least 11 nights of acclimatization is suggested before ascending to heights above 18,000 feet, officially considered “extreme high altitude.”

Even then, altitude sickness is unpredictable and the only cure is to descend, which can turn a cold adventure of a lifetime into a wet blanket.

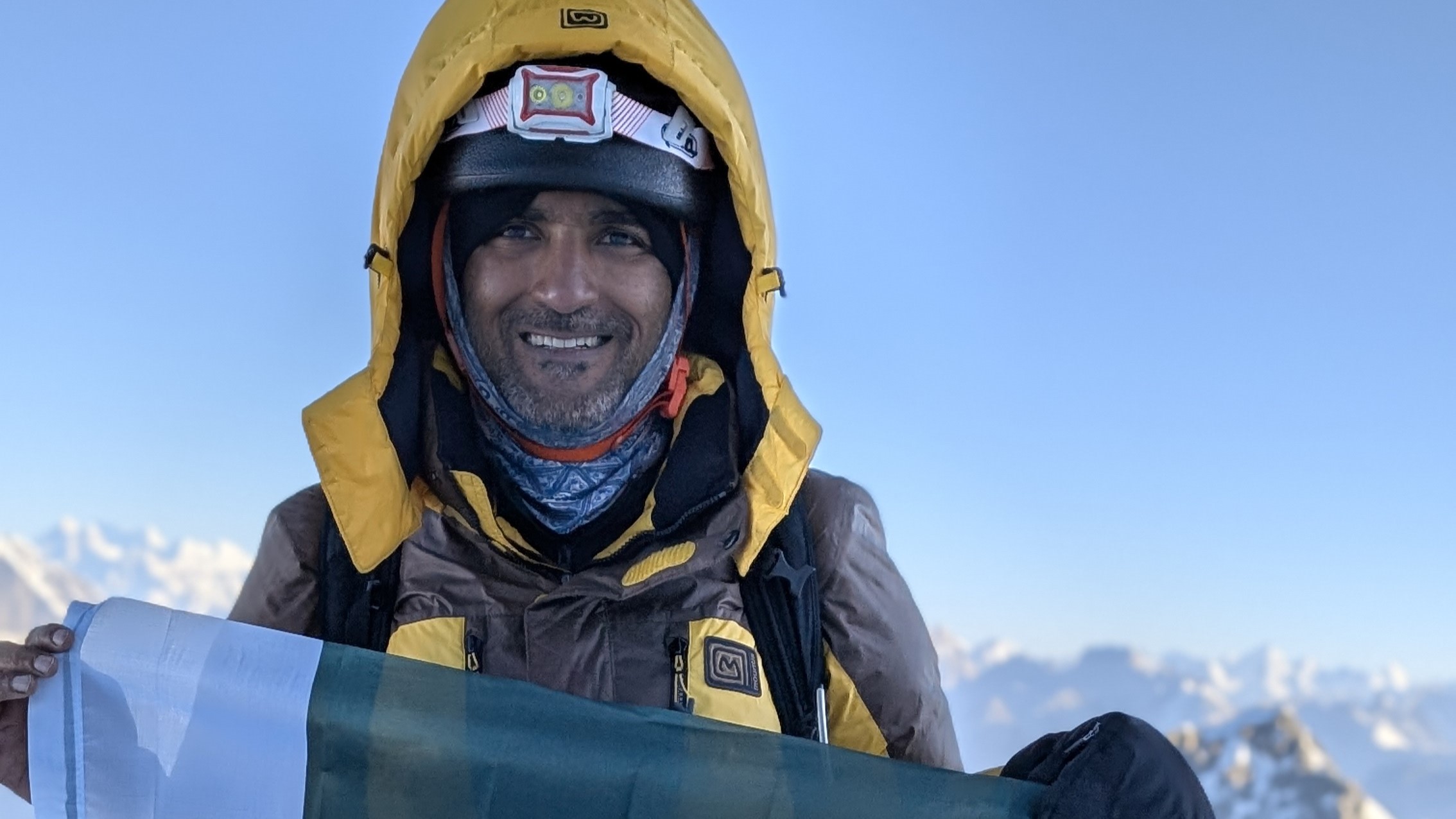

This summer, Pakistani mountaineer Umer Latif decided to try an experiment. Could he climb Khusar Gang, at nearly 20,000 feet above sea level, with only three days of acclimatization? After all, he was squeezing the trek in between expeditions to Iceland and Madagascar and wouldn’t have the recommended minimum time.

Latif lives in Lahore, just 650 feet above sea level, where runs an adventure trekking company. He’s well-accustomed to the physical conditioning required for high altitude treks like this one, which would require nearly 5,000 feet of elevation gain on an average slope angle of 29 degrees. He trains in his home gym, using step-up boxes, weights, an elliptical trainer and a weighted backpack (all while using his Scarpa mountaineering boots to break them in). Physical conditioning, he says, is the first and most important step of a journey like this.

“I think when someone does any adventure, they first have to make sure the physical endurance is there,” says Latif.

“If my legs are not up to it, if my muscles do not have the basic strength, and muscular endurance, I would fail quickly.”

This time, however, Latif tried adding a secondary component to his training: breathwork.

"You do it once and you know how to do it”

Following a five-week High Altitude Breathwork Training program developed by a US-based company Recal Travel, Latif performed short breathing exercises to try to improve his VO2 max – the maximum amount of oxygen his body is able to use when he is doing vigorous activity like climbing a mountain.

The program entails breathing exercises totaling between 20 and 30 minutes per day. The exercises focus on improving your respiratory efficiency, making biochemical adaptations required for altitude such as increasing your hemoglobin concentration and carbon dioxide tolerance, and strengthening your respiratory muscles like your diaphragm.

Latif says he saw a marked improvement in his carbon dioxide tolerance in his very first week of training. Once he got on the mountain, he was able to monitor his Blood Oxygen Saturation Level – the amount of oxygen in his red blood cells – using his Garmin Epix watch, and says it was higher than it’s ever been.

“Based on my objective measurement, it has a huge benefit, and the good thing about Recal training is that you do it once and you know how to do it.”

"It's kind of like hitting the cheat code on your nervous system"

The program was developed by Recal founder Anthony Lorubbio, a Boulder, Colorado resident with a business background. He tells me he came up with the idea after reading research on breathwork as high altitude simulation training, which traditionally has involved more complex practices such as wearing a high altitude training mask or spending time in a hypobaric chamber.

A 2010 study on 14 military personnel who were part of a climbing expedition to the Nepali Himalayas published in Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine showed a 15 percent increase in respiratory strength in just 4 - 6 weeks of training the respiratory muscles. The subjects who integrated Respiratory Muscle Training into their endurance protocols experienced a 12 percent improvement in their VO2 max. A 2012 study found that slow deep breathing improves oxygen efficiency and reduces systemic and pulmonary blood pressure at high altitudes.

Lorubbio’s research led him to the Wim Hof method and from there to The Oxygen Advantage, a popular breathwork training program devised by Patrick McKeown.

“I found that breath work was the type of mindfulness that really resonated the best,” says Lorubbio.

“I like to say it's kind of like hitting the cheat code on your nervous system to reach a deep level of presence.”

Working with UK-based breath coach David “Jacko” Jackson, Lorubbio created the program and tested it on himself with what he calls a sea level to 14er challenge. He showed up in Colorado without doing any sort of acclimatization and immediately climbed a 14er – that’s a peak over 14,000 feet.

“That was actually the first time I had ever been to that type of altitude.”

To help measure the potential effects of his breathwork training, Lorubbio hiked with a control group who had not done the training, but who lived at a higher elevation.

“The differences between how our bodies responded to the altitude, and how quickly we were able to move through the mountain at that type of elevation, and then how I felt versus the control group was quite significant.”

Next up, Lorubbio took the training to the 18,491-foot summit of Mexico’s Pico de Orizaba, the third-highest mountain in North America, where he brought along a medical doctor to observe the effects.

“He was really pleasantly surprised with how efficiently and quickly we were moving, how we were able to keep our hypoxic levels down,” says Lorubbio, who explains that the test group used pulse oximeters to track their blood saturation levels.

"You're going to be oxygenating your body more efficiently at altitude”

A key part of the training is improving your carbon dioxide tolerance. As Lorubbio explains, this helps prevent you from overbreathing (hyperventilating) on the mountain due to an urge to exhale constantly. Instead, the program teaches you to breathe more slowly and deeply.

“If you can tolerate more carbon dioxide on the mountain, not only will you feel less breathless, you'll actually be allowing your hemoglobin to be delivering oxygen more efficiently throughout your body.”

Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying blood cell, and it requires a certain level of carbon dioxide – or, more specifically, a lower blood pH – to do its job.

“So if you can tolerate more carbon dioxide, and these breath work training protocols are designed to do just that, then you're actually going to be oxygenating your body more efficiently at altitude.”

For Latif, the program seems to have been a success. Though his guide ended up succumbing to altitude sickness on day two of the trek despite having previously hiked five peaks over 8,000 meters including K2 and Nanga Parbat (altitude sickness can strike anyone, at any time), Latif set off for the summit at midnight on the 14th of August, after just three nights at high altitude and a couple of days of trekking.

“Even at 5,200 meters, my blood saturation was 80 percent or above. I think when you go straight from approximate sea level to 5,000 meters in four or five days, it's amazing.”

He submitted at 6 a.m. where he says he saw one of the most beautiful sunrises of his life, then hiked for four hours back down to camp where he had breakfast and took a nap.

“The plan was to come down in the next two days, but I woke up, I felt high in energy, and I said, okay, we go down the same day.”

And so, just hours after their summit, the team began their descent and by that evening Latif was back in Khaplu feasting on the hotel buffet.

To be clear, these aren’t randomized controlled trials, and both men are quick to stress that this training isn’t a replacement for acclimatization.

“This really homes in on making some key adaptations that are going to be worthwhile when they show up on the mountain, and they're forced to deal with the thinner air and the hypoxic levels that they'll face,” says Lorubbio.

Latif says he thinks the exercises are particularly helpful for people like him, who live at a very low altitude and want to go into high altitudes – and don’t necessarily have the time or means to spend weeks in a hypobaric chamber.

“I think they are convenient, and I immediately saw an improvement in the way I breathe,” says Latif, who also says the training has helped to breathe better in everyday life.

“I would still say, irrespective of whichever training someone does, they should go up slowly. But I did it fast. And definitely Recal had some help in it.”