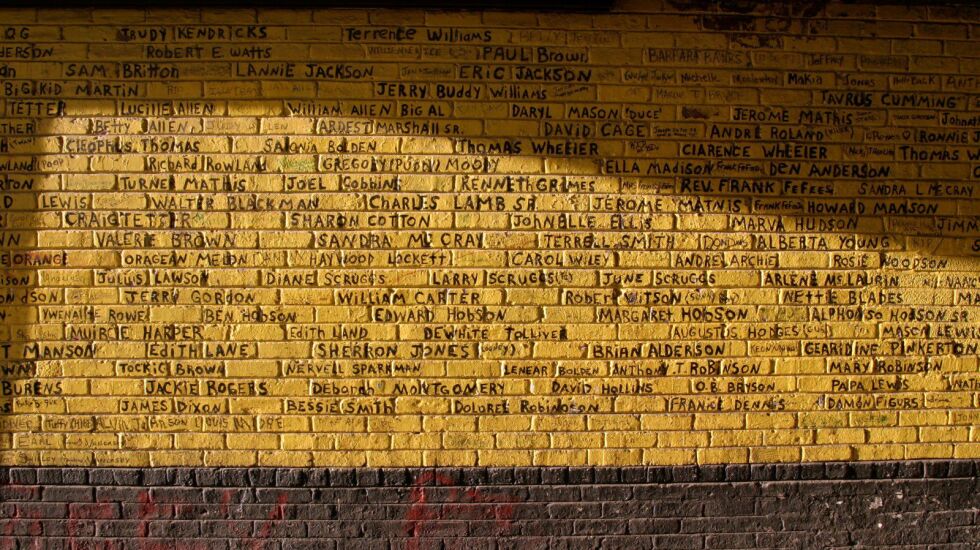

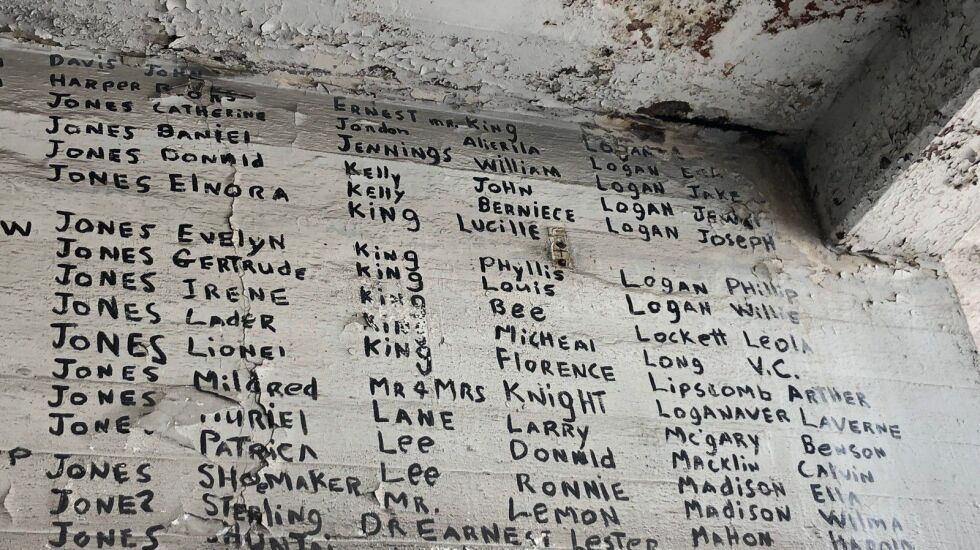

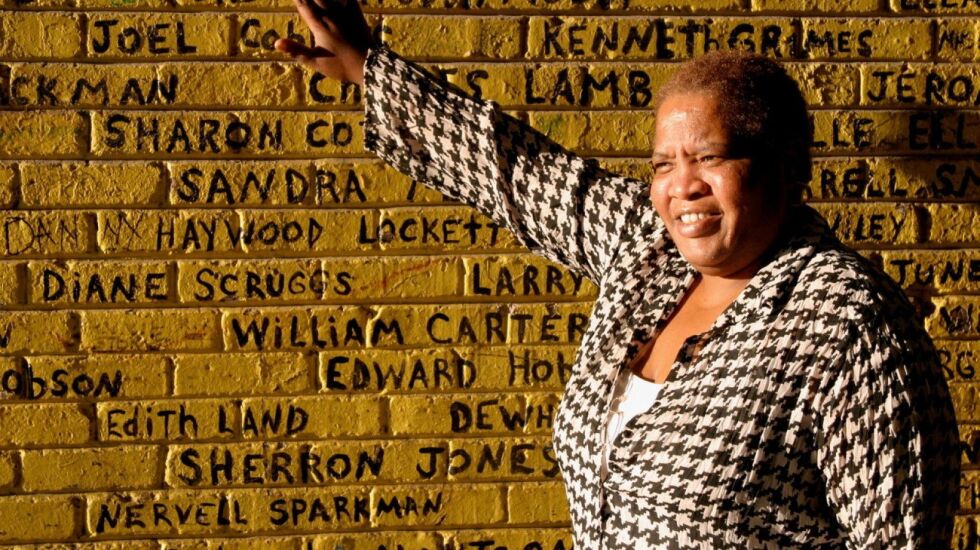

Some of the bricks are chipped. Some of the paint is faded. But to people who live — or once lived — in the Altgeld Gardens public housing community, this is their Memorial Wall, a place of family record for lost loved ones and a place of history.

A young man stops to scan the names.

“This is my grandmama name right here, Leola Lockett,” he says, declining to give his name. “She was a beautiful lady. These are all the people who’s raised up out here, who was part of the community. I miss ’em all.”

Baron Johnson grew up in Altgeld Gardens and comes back every year for an “old-timers” picnic. He gets sentimental recalling his time there: the baseball teams, late-night roller-skating in a school gymnasium, the annual flower festival, a village in which people looked out for each other’s kids.

“And everybody, when they come up to visit, they recognize the names and their memories,” Johnson says. “So the wall is kind of like a historic monument for everybody who used to live or still lives in Altgeld Gardens.”

Still, parts of the wall’s history is uncertain, and its future is even more unclear. The Memorial Wall sits in the breezeway of a dilapidated, privately owned commercial building at the center of the community. That building has been in demolition court for the last few years, and the wall’s future is tied up with it.

Public housing at city’s edge

Altgeld Gardens is the most isolated of Chicago’s public housing communities. Completed in the mid-1940s, the complex was a racially segregated development for African Americans — war workers in the nearby armaments industry and returning veterans.

In contrast to the high-rises that the Chicago Housing Authority later built, its original 1,500 units were two-story brick rowhouses laid out on curving streets, each with its own small front yard. The Gardens, as it’s often called, had a suburban feel.

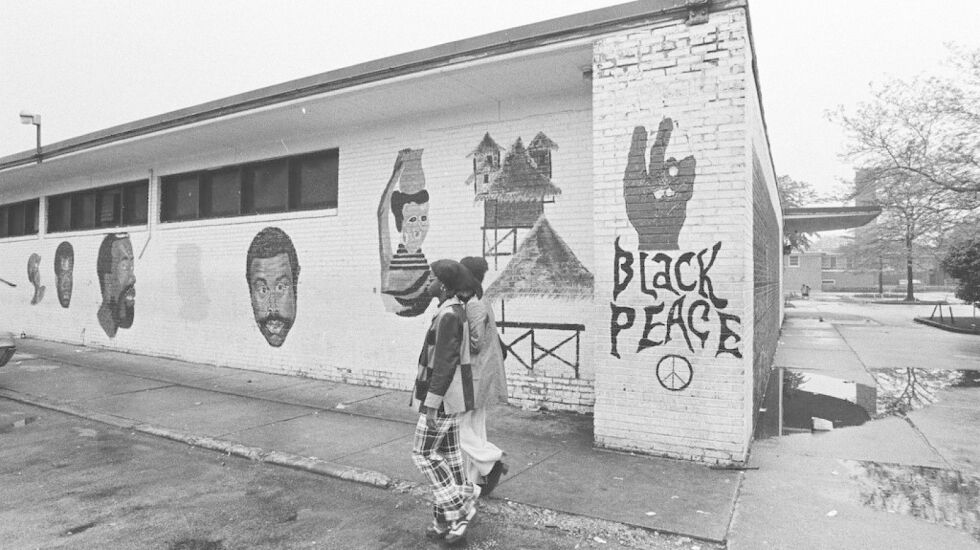

At the heart of the Altgeld development was a privately owned commercial building that for decades housed a collection of Black-owned businesses: a drugstore, a shoe-repair shop, the Funky London lounge, a barber shop, the Garden of Eden beauty shop and, most important, a grocery store.

This unusual building was designed by brothers George Keck and William Keck, the Keck & Keck architectural team who dreamed up the “House of Tomorrow” for Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair. Built in the modernist style, this blocklong building had a swooping, cantilevered canopy and curving, glassy front wall. It served as a kind of town center, where people shopped and socialized.

Residents called the building Up-Top, and the Memorial Wall took root there in a covered breezeway that runs through the building.

From grief to self-expression

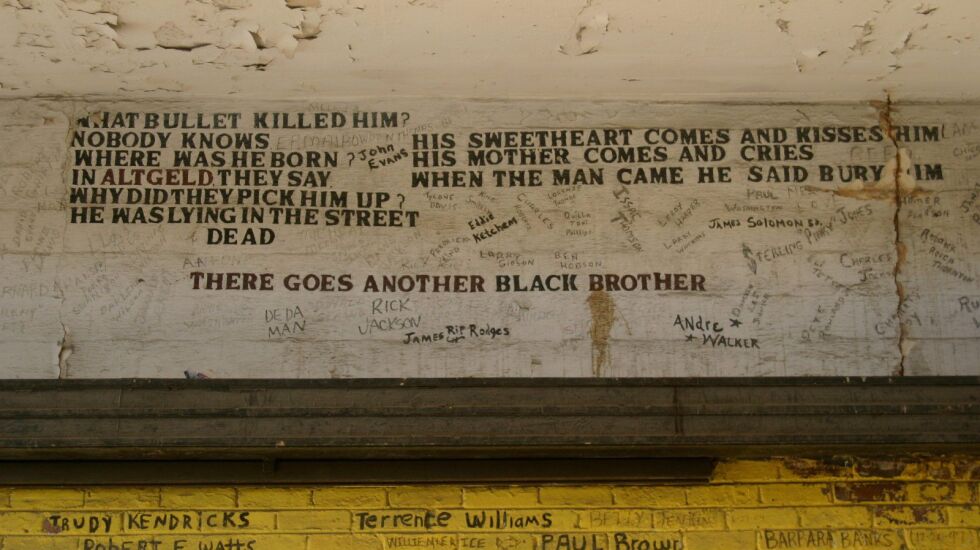

The exact origin of the yellow brick Memorial Wall is hard to know. In its early days, it had a different look — and function — tied to an important event in Altgeld Gardens’ history.

Seth Ibrahim was an imam at the Mosque of Umar on the South Side. In the late 1960s, though, was a young activist living in Altgeld Gardens.

Today’s wall, he says, started off as a “Wall of Pride” or “Wall of Hope” after 17-year-old Sterling “Pinky” Jones was shot and killed on Christmas Day in 1969. That was three weeks after Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, was gunned down by police.

The killing of Jones, a popular and active Black Panther Party member, was never solved.

In the days and months after he died, Altgeld Gardens was a tinderbox. Violence seemed ready to erupt, Ibrahim says, and young people needed somewhere to put their energy and grief. Ibrahim and his activist friends wanted to direct that energy — and that grief — to something positive. They came up with the idea of using Up-Top as a place where people could express their views on the Black Power Movement, post notes of encouragement to their neighbors, write poetry and paint murals.

Jones’ name went up in a prominent spot on the northeast side of Up-Top’s breezeway. And the CHA provided paint for the mural effort and sent over a talented employee who painted a large mural of Malcolm X.

That mural spurred others to action, Ibrahim says. Over time, the murals, political statements, poetry and words of encouragement spilled beyond the breezeway and onto the outside walls of Up-Top. The names memorializing people who’d lived and died at Altgeld became concentrated in the breezeway.

Those are the names that remain on Altgeld’s yellow brick Memorial Wall 50 years later.

Legacy of environmental racism

Altgeld Gardens has been home to some larger-than-life figures, among them the late Hazel Johnson, known as the “Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement.”

After her husband died of cancer at a young age, Johnson confronted government officials and industries about hazardous waste dumped near low-income and minority communities like hers. She started the environmental justice organization People for Community Recovery, now run by her daughter Cheryl Johnson.

“The majority of those people on that wall died from cancer,” Cheryl Johnson says. “And we still have a higher incidence of cancer in this area than any other. And now we have a lot of cardiovascular problems in the area, and that signifies something from breathing this polluted air in our community.”

Altgeld Gardens was built on the edge of a dump for what was then the town of Pullman. In 1892 alone, almost 700 million pounds of human waste and liquid sludge was dumped into the Pullman “sewage farm” just west of what today is Altgeld Gardens.

For Johnson, the wall is testament to the many whose lives were shortened because of exposure to hazardous waste and pollution — and a reminder of why her mother’s work was so important.

“That’s what that wall defines to me — that environmental racism was heavily practiced in Chicago,” Johnson says. “That’s what that wall is to me.”

Last April, the entire Altgeld Gardens complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. That led some to think the Memorial Wall would be preserved.

But City Hall is in demolition court with the owner of the Up-Top building at Altgeld Gardens, so that building is endangered — which means the Memorial Wall also is endangered.

But it’s possible, for instance, that the wall could be taken down and then reassembled elsewhere. Or it might be memorialized, say, through photographs.

If the Altgeld Gardens community wants to keep the Memorial Wall intact and where it is, that means saving the building it sits in.

“The only way to protect a building in the city of Chicago,” says Ward Miller, executive director of Preservation Chicago, “is by having it made a designated Chicago landmark, which is protecting the building by ordinance.”

That requires a Chicago City Council vote. The first step in that process, which anyone can take, is completing a “Suggestion for Chicago Landmark” form. It lists seven criteria to show a site is worthy — including history, cultural significance and unique architecture — though only any two of the seven need to be met.

The Chicago Landmark Designation Process site provides more information on what might happen with suggestions. And organizations like Preservation Chicago or Landmarks Illinois might be able to help with research for the suggestion form.

Typically, Miller says, city officials don’t like to landmark buildings that are in demolition court, so it could be a tough road for the Memorial Wall at Altgeld Gardens.

“At the end of the day,” Miller says, “we rely on the Altgeld community to tell us if this is important to them.”

To some, the wall is a link to their past, to history and to the fight for environmental justice.

To others, including Belinda McGrew, the priority needs to be bringing back essential businesses — even if that comes at the cost of tearing down the wall.

“Most of the people that’s on the wall are not here; the family is not here anymore,” McGrew says. “We need grocery stores out here. We don’t have that anymore.”

“If you give me a magic wand, what I’m going to do is create a new wall and put all the names of the people who passed away and then tear down the entire building and create a store for the community,” another Altgeld Gardens resident says.

For Marguerite Jacobs, the idea of losing the Memorial Wall is painful.

“I would hate it,” Jacobs says. “I would hate it. I mean this is the core of Altgeld. So why don’t we rebuild instead of tear it down?”