Hard-rockin’ anthems; tender piano ballads; impeccable vocal harmonies; snazzy outfits; a charismatic frontman. That’s a fair description of the formula that took Queen to the top of the charts and global superstardom. It also describes US 70s band The Raspberries. While Queen conquered the world, however, The Raspberries remain overlooked and virtually unknown, despite having had John Lennon and Keith Moon among their fans.

Few songs from the early 70s epitomised the ‘power pop’ style as splendidly as The Raspberries’ Go All the Way. Three-and-a-half minutes of pure pop bliss it blended the best bits of early Beatles and Who. While the title gave a not-so-subtle clue to its lyrical content, the song offered a unique spin – it was sung from the point of view of the girl.

“I always thought if it saw daylight, one of two things would happen,” says Raspberries singer/guitarist Eric Carmen (best-known for his solo big hit ballad All By Myself in ’76). “Either it’ll get banned because it’s dirty – then maybe people will buy the album to check it out; or if it ever gets on the radio, I think it’ll just be a hit based on the title alone.” It did get on the radio, and was almost a US chart topper. But for myriad reasons The Raspberries were unable to use that single to catapult their career skywards.

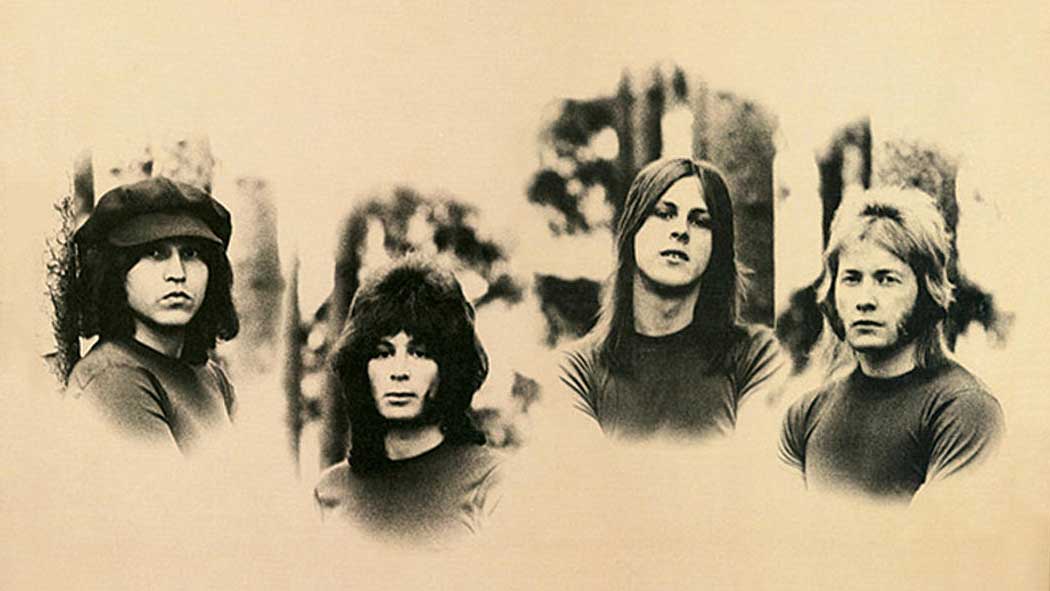

By the 70s, the US city of Cleveland, Ohio, had been hit hard when the once thriving steel mill and automobile manufacturing industries had come to a standstill. It was not the kind of place you’d you’d expect a sunny power pop group like The Raspberries to come from. But that’s where Carmen, guitarist Wally Bryson, bassist Dave Smalley, and drummer Jim Bonfanti called home.

Smitten by many British bands, during the late 60s Carmen had heard about a local band that was creating a stir: “I was going to high school, and there was talk that there was this really great band, The Choir. I ventured out to see them, and they were awesome – Wally, Dave and Jim were all members. They played all the chords right, they sang the harmony parts right. I looked up at that stage and said, boy, if I could get into that band we could really do some damage.” Meanwhile, Carmen bided his time fronting his own band, Cyrus Erie, who also became a local favourite.

With The Choir and Cyrus Erie unable to expand their respective followings outside Cleveland, both bands eventually split in 1970. Soon after, Carmen hatched a plan: “At that time, all the stuff that I grew up loving, which was three-and-a-halfminute singles – well-crafted pop songs with great melodies; The Beatles, The Hollies, The Who, The Byrds – was going away.

"Replacing it on radio was Cream and Traffic; it wasn’t the three-minute pop stuff that I loved. So Jim and I sat down and said what’s happening is not what we love, so let’s start a band and make it the antithesis of everything that’s going on now – three-and-a-half-minute pop songs; no extended guitar solos, no boring drum solos. None of this sort of self-indulgent stuff that all the bands were doing."

With their short hair, matching suits, and Beatlesque sound, The Raspberries ran in the opposite direction to the prevailing hard rock mentality of the Cleveland scene. Originally comprised of Carmen, Bryson, Bonfanti and bassist John Aleksic (their first choice, Smalley, was serving in Vietnam at the time), the group set out to see how their three-minute pop stuff would go down. It went down a storm, but the band hit a dead end while trying to expand their local following.

“You could hardly get out of Cleveland,” Bryson recalls. “Nobody wanted to talk to you – they didn’t think anybody had any real talent here. So for us and The James Gang, it was tough to ‘get out of Dodge’ and hit the rest of the world.”

After ousting Aleksic in 1971, The Raspberries continued as a trio, with Carmen taking over on bass. When Smalley returned home after his tour of duty in Vietnam he was brought into the band first as rhythm guitarist and later as bassist.

For the next part of the plan they bought tickets and went east to New York. There, with a demo in hand, the group ‘ambushed’ producer Jimmy Ienner in New York’s Grand Central Station, imploring him to listen to their tunes right then and there. Ienner was impressed with what he heard. So much so that he soon became their producer, and helped the band sign to industry giant Capitol Records.

The Raspberries went into York’s famed Record Plant studios (where the group would record all their albums) with Ienner and got to work. But they suffered the same problem that has dogged countless bands: how to recreate in the studio the energy generated at their live shows.

“[Engineers] wanted the guitar really clean, low volume,” Bryson explains. “You can’t really imitate what you’re doing live, and you can’t get any balls. It was a big struggle to record and have it come out the way I heard in my head.”

When Carmen heard the first version of Go All The Way he was appalled: “When I brought the song to the band, I explained it by saying: ‘It’s sort of a concept song. Picture this, guys: the song opens and it’s The Who playing Won’t Get Fooled Again. You hit the verse, and it’s suddenly The Beach Boys playing Don’t Worry Baby – with McCartney singing. Then when the chorus comes, the Left Banke come in and sing background. Then it goes back to The Who.’ They were all looking at me like: ‘What? Are you nuts?!’

“When we got into the studio, it just wasn’t flying. I remember going to Jimmy Ienner and begging him to leave it off the record.”

With the song that would later become a bona fide hit almost deleted from the album, engineer Shelly Yakus attempted to revive the track by sticking it through a studio gizmo called a limiter. Carmen: “I came in the studio, and they played this thing for me. It was like: ‘Oh my God. There’s my record!’”

The Raspberries had the song that would launch their career.

A few months after the release of their self-titled debut album (complete with raspberry-scented scratch-’n’-sniff cover) in 1972, Go All The Way raced up the US chart, peaking at No.5 But there was little else on the album – comprised mostly of mid-tempo material and ballads – that resembled the rockin’ nature of their hit.

Another career swerve occurred when the group planned the photo for the cover of their follow-up album, Fresh (1973). With all their favourite bands adopting an identifiable image, The Raspberries came up with an ill-advised fashion idea: matching white suits – looking like a bunch of Tony Maneros from Saturday Night Fever.

Musically, though, Fresh was an improvement on the debut (and would be their highest charting album, thanks in part to the hit single I Wanna Be With You, one of their best ballads in Let’s Pretend, and the Beach Boys tribute Drivin’ Around. It was around this time that Carmen became the group’s chief songwriter, leaving Bryson out in the cold creatively and pissed off.

“I was contemplating leaving at that time,” he says. “I went from writing or co-writing [several] songs on the first album to writing one on the second album. So there were some arguments over songwriting. But I ended up staying.”

A wise move. The group’s third album, 1973’s rawer and more aggressive Side 3 – with such gems as Tonight (later covered by Mötley Crüe), Ecstasy and Hard To Get Over A Heartbreak – was arguably their finest.

“I think Side 3 was the first time we began to sound on record the way we actually sound,” Carmen says. “But we began to have friction within the band about, ‘Is this direction working?’ Dave was moving off into a more country-ish direction, and I was not happy with that.”

Additionally, Carmen recalls that it didn’t help that the group were being handled by a succession of shady managers who didn’t look after their best interests properly. “The frustration of doing what we were doing – having hit records and having no money, touring and playing crummy places – was starting to overwhelm us. It was starting to get tense.”

Things worsened when their label Capitol continued to push an image of the group that they neither had nor wanted.

“We had always been musicians first and foremost,” Carmen explains. “We wrote our own songs, we played our own instruments, we sang all the parts. When Capitol said: ‘We’re going to organise interviews for you’, I remember us all sitting in a big conference room at the Capitol Tower in Los Angeles, waiting for Rolling Stone, Creem and Crawdaddy to come in. And in would walk Fave and 16 Magazine – ‘What’s your favourite colour?’, ‘What do you like to do on a date?’

"And the next thing you knew we were all over 16 Magazine. And no self-respecting 17 or 18-year-old guy was going to say: ‘Oh, those guys are cool, my little sister likes them’. Because of the marketing campaign of Capitol – who really didn’t know what we were – they just blew off the whole album-buying audience. And that was really the kiss of death for the band.”

Despite the mounting problems and frustrations, The Raspberries’ original lineup held it together a bit longer. And for a brief moment everything fell into place when they decided to gamble and headline New York’s famed Carnegie Hall.

Carmen: “I thought it was the best show that we ever played – by far. Everything came together for that show. We decided: wear whatever you want but it’s got to be black; the backdrop at Carnegie Hall was completely white, so when we walked on stage the effect of it all was like looking at a black-and-white movie. Which was cooler than I ever could have anticipated.

“I thought: ‘What would be the last thing that a New York audience would expect us to do?’ I eventually came up with the idea that with all the Beatles comparisons, the last thing they would ever expect us to do would be to open with a Beatles song. So I figured out a way to play the intro of Ticket To Ride and segue it right into I Wanna Be With You. It worked like a charm. The audience were just stunned. And then when we launched into I Wanna Be With You the place just roared, and we owned them from that minute on.”

Despite The Raspberries winning over New York, Smalley and Bonfanti realised they were moving in a different direction, and soon jumped ship. Carmen and Bryson opted to carry on with replacement members – bassist Scott McCarl and ex-Cyrus Erie drummer Michael McBride – although the decision was tough for Bryson: “They [Smalley and Bonfanti] were buddies of mine from The Choir. It was a real difficult situation. I felt real torn. In the end I decided to stay, and got to work with Scott McCarl, which was great, and my brother-in-law Michael.”

The new line-up came up with yet another pop masterpiece in 1974’s Starting Over, the highlights of which included the Queen-like epic Overnight Sensation (Hit Record) and Play On. But, as evidenced by such as the title track and the prophetic The Party’s Over, the group knew the writing was on the wall. Recording at New York’s Record Plant, they got to meet one of their heroes, John Lennon, who was producing Harry Nilsson’s Pussy Cats there.

“[Lennon and Nilsson] were recording Loop De Loop,” Carmen recalls, “and he had a bunch of school kids in there, clapping hands. He needed some people who could actually clap and keep time, so he came and got Michael and I. Of course, we were out of our minds – ‘He wants us to clap on his song!’

“Later on, Jimmy Ienner had told me that one night when he was working on the mix of Overnight Sensation…, John had come by and said: ‘Fabulous. Love it.’”

A few months later The Raspberries got to meet another of their heroes when Who drummer Keith Moon jumped on stage to jam during a performance at the Whisky A-Go-Go in LA.

“He came up, and I guess he had some drinks,” Bryson recalls. “But in about 20 seconds the ‘fog’ lifted, and he really played great. We played All Right Now. It was a good time. I just thought: ‘Wow, this means we made it – Keith Moon is jamming with us!’ I was blown away.”

With little money in their pockets, and Starting Over soon proving to be their lowest-charting album, tensions were high. Following an ugly physical confrontation between Bryson and Carmen in a Chicago parking lot, Bryson walked out of the door and slammed it shut behind him. After playing the rest of the scheduled dates of a tour as a three-piece, The Raspberries split in 1975.

In the years since then, Carmen launched a successful solo career (huge hits with All By Myself and Hungry Eyes), while Bryson, Smalley and Bonfanti played in other groups: Bryson in Tattoo and Fotomaker; Smalley and Bonfanti in Dynamite. But The Raspberries’ stature continued to grow, as they left an unmistakable imprint on bands like Kiss and Cheap Trick, and Go All The Way was introduced to a new generation via Cameron Crowe’s band-on-tour movie Almost Famous.

As a result, rumours of an original Raspberries line-up reunion appeared throughout the years, but didn’t come to fruition until 2004, when Carmen, Bryson, Smalley and Bonfanti played a handful of gigs together at House Of Blues venues in the US.

“Glad to be buddies again and making music,” Bryson said. “And, man, our fans are the best in the world. They just wouldn’t let us die. They waited all these years. It’s astounding. Our music lived on, and forced us to get back together.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 81, published in July 2005.