Dance is usually added to Broadway musicals during staging, and sometimes it can be almost an afterthought.

But in the case of “West Side Story,” the role of movement was considered from the earliest moments of the work’s genesis, and the art form is integral to the very essence of this celebrated 1957 musical.

Indeed, choreographer and stage director Jerome Robbins conceived the work and was a key part of a dream creative team that also included composer Leonard Bernstein, lyricist Stephen Sondheim and playwright Arthur Laurents.

Robbins’ now-legendary choreography will be front and center in June as the Lyric Opera of Chicago revives its 2019 staging — a co-production with the Houston Grand Opera and Glimmerglass Festival in Cooperstown, New York.

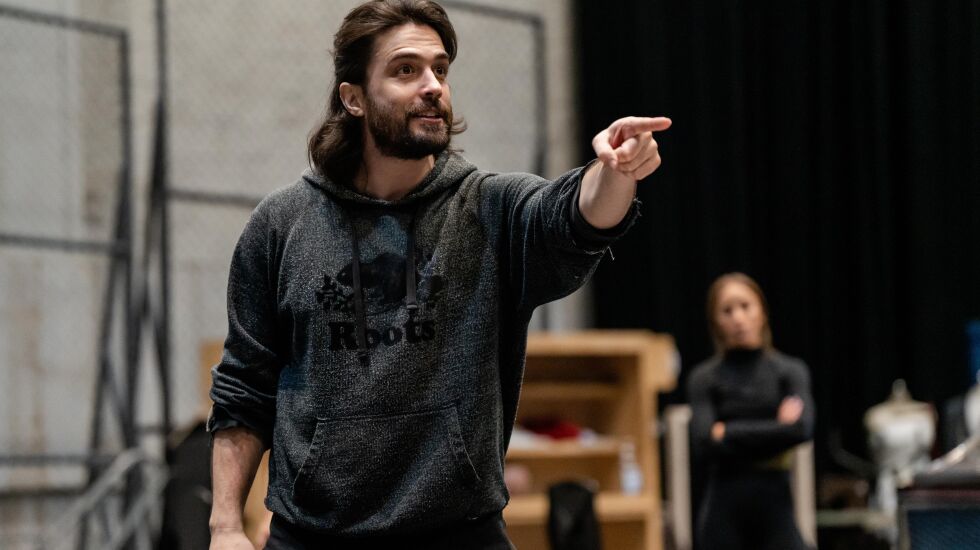

“I’ve done it dozens of times,” said Tony Award-nominated choreographer Joshua Bergasse, who is responsible for reproducing Robbins’ steps. “The piece, to me is so perfect and the craft of it is so genius that I feel that every time I do it, I peel back another layer of the onion and learn something else.”

The former dancer first performed in “West Side Story” in 1995 under the oversight of Alan Johnson, who appeared in the original Broadway production. Bergasse later assisted Johnson in re-staging Robbins’ choreography in subsequent productions and then struck out on his own.

“West Side Story” is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” with the Montague and Capulet families replaced by street gangs of different ethnic backgrounds — the Sharks and Jets — and the action taking place on New York’s Upper West Side in the 1950s.

Unlike some musicals, in which the story stops and the dancing starts, the narrative flows seamlessly through the choreography. And because movement plays such an integral role in this musical, virtually everyone in the 37-member cast has to be a first-rate dancer.

“When people are dancing,” said Bergasse, who is making his Lyric Opera debut, “not only does the story continue, but it’s almost continuing at a heightened level. It’s portraying emotions and feelings that transcend the dialogue and even the music.”

In rehearsals, he has constantly reminded the dancers of what he calls the “intention” of each movement. “Why are they doing this step?” he said. “What does it mean? What is their character trying to say?”

As an example, he cites a motif that Riff has at the beginning of the prologue that is called the “sailing step,” because of the character’s upraised arms as he circles the stage. “It needs to be done in a very specific way or it just looks like a dance step,” Bergasse said.

Brett Thiele, a veteran Broadway performer portraying Riff, the leader of the Sharks, agreed. He compared dancing the choreography in “West Side Story,” particularly the sailing step, to an actor interpreting text in a play.

“It’s a movement that is so deep yet so simple,” Thiele said. “It’s just the raising of an arm, but it represents so much of the beginning of the story, to show pride for what you are doing, pride of where you come from and ownership of where you are.”

Also important to dancers in “West Side Story” is conveying the jazzy thrust and rhythmic drive of Bernstein’s kinetic music. “For certain things, there’s a physical attack that the dancers have to have,” Bergasse said.

Many of the gang members have what he described as repressed rage because of the socio-economic challenges they face, and that rage comes through in the visceral physicality of the choreography.

Each production of “West Side Story” is inevitably different because the members of every cast bring their own perspectives and experiences to the story, and there is room within the choreography for personal expression.

“There are steps, there are legs, there are beautiful pointed feet and there are jumps that touch the ceiling,” said Amanda Castro, “and within that there is space for you to create the worlds of these teens who are struggling, who are just trying to survive.”

Castro, who performed for four years with Urban Bush Women, a well-respected contemporary dance company based in Brooklyn, portrays Anita. The character works in a bridal shop with her friend Maria, the show’s female lead. The role was originally portrayed by Broadway star Chita Rivera.

This production of “West Side Story” runs for 2½ hours including one intermission, and much of it is filled with what Castro called “ginormous dance numbers.” To get through it all, she does a warm-up before the cast warm-up at each show and a cool-down after the cast cool-down.

“It’s beyond physical demanding,” she said. “But it’s worth it, because it’s so much fun.”