Jane Stafford on the novel that won the 2023 Ockham fiction prize on Wednesday night

It is difficult for Pākehā writers to do the spiritual, although they have often felt the need to. Colonial poets, blind to the pre-existing mythic landscapes around them, lamented the absence of magic in the New Zealand setting. "Why have we in these isles no fairy dell?", warbled Alexander Bathgate. The importation of European Romanticism’s idea of God-in-Nature, Wordsworth’s "sense sublime … Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns/ And the round ocean and the living air,/ And the blue sky, and in the mind of man", is difficult to sustain when you are busy burning the bush, clearing the landscape, and substituting trim paddocks and the frozen meat trade.

A good proportion of 19th Century New Zealand may have been church-going, but the secular basis of settlement was officially established from the outset, and conventionally religious colonial authors are hard to find. Several literary toffs among the early settlers – for example, Alfred Domett, friend of Browning or Thomas Arnold, brother of Matthew – toyed with fashionable Darwinian doubt, the antithesis of the spiritual.

In the absence of the home-grown, there was a tendency for Pākehā authors to cut and paste spiritual systems ‘borrowed’ from others. The results, in aesthetic terms, have not been great. The late-colonial authors of Maoriland co-opted Māori spirituality, producing a literature of pseudo-Indigenous voices on "Pakeha harp strings tuned by a stranger", as the not unaware Thomas Bracken put it. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Blanche Baughan’s affiliation to Vedanta and the then fashionable teachings of Vivekananda produced perhaps one of the worst poems of the New Zealand canon where she compares her dog’s acute spiritual awareness to her own inability to feel her way into the status of a Great Soul. James K Baxter’s spiritual gropings likewise looked offshore, following a continuum from admiration to affiliation to appropriation, first of Indian religious belief and then, in Hiruhārama Jerusalem, of te ao Māori. Like his public image, these poems haven’t worn well – matey conversations with Christ sprinkled with te reo, self-flagellation, and lustful musings.

Aotearoa’s mid-20th Century divorce from Britain may have been bracingly decolonising in a Pākehā sort of way. But it is registered in literature as scary and devoid of reassurance, spiritual or otherwise, R.A.K. Mason’s "solitary hard-assaulted spot fixed at the friendless outer edge of space". Allen Curnow in his 1941 poem "House and Land" pictured a despiritualised landscape of "great gloom", "a land of settlers with never a soul at home". Janet Frame gave her unsteady narrators occasional glimpses of something somewhere else, faces in the water, but then briskly returned them to their psychiatric ward.

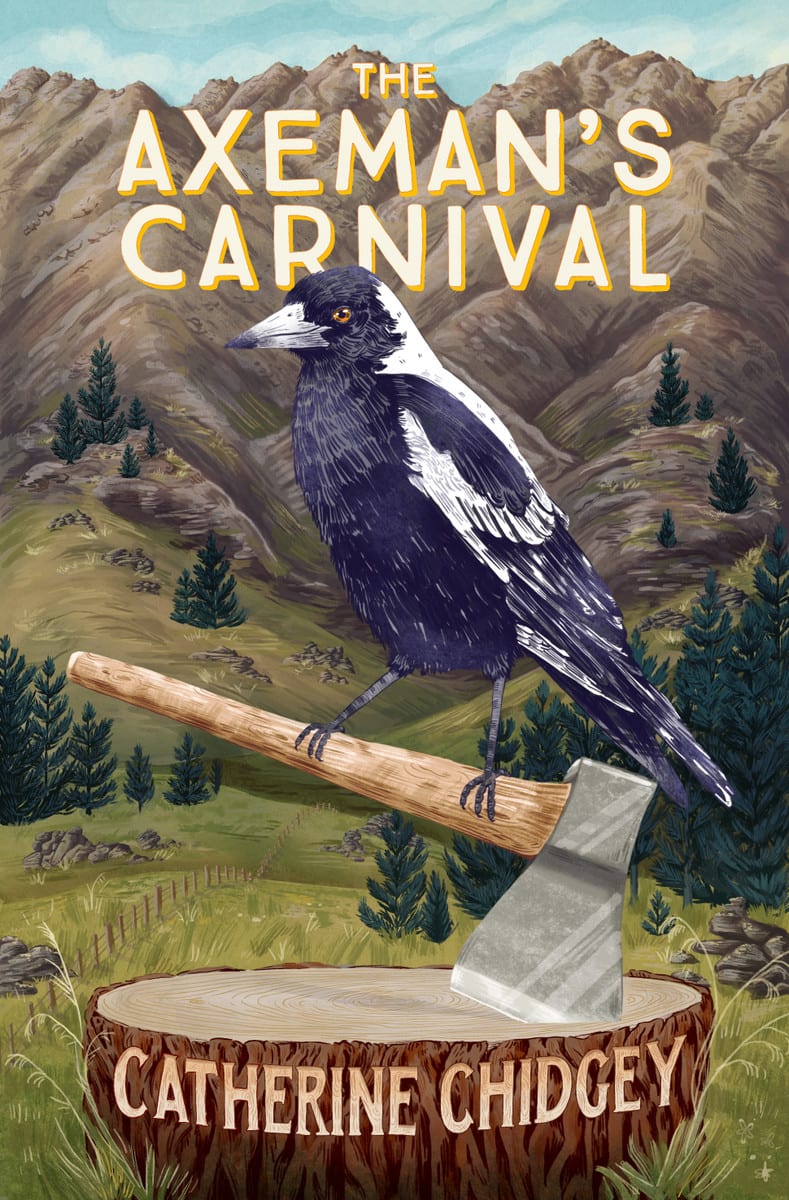

In her novel The Axeman's Carnival, winner of this year's fiction prize at the Ockham book awards, Catherine Chidgey is reminiscent of Frame, not least her keen ear for social satire and the narrative’s deftly orchestrated shifts in register. For her the farm is Curnowesque – joyless, puritanical, imbued with an everyday violence that is socially licensed and covertly murderous. But in the pines on its margins, the magpies are watching.

*

I really don’t care for talking animals. This has not been a problem in my day-to-day life, but I have had to take pains to avoid them in fiction. Too cute; too limited in what they could conceivably narrate; tending towards the sentimental, the sententious, or, even worse, fantasy.

So I approached The Axeman’s Carnival with apprehension. A magpie narrator and not of the naturalistic, incoherent, ‘quardle ordle ardle wardle doodle’ variety. A first sentence: "When I was a little chick, not even a chick but a pink and naked thing …" Hoo boy.

But I was wrong. I still do not resile from the talking animal aversion. But I make this novel the singular exception. Why is this? Partly it is because Chidgey is such a skillful writer, with a control of diction and tone, a crafty deployment of irony, an ability to catch the patterns and nuances of ordinary, often cliched speech, pinning down, in a manner that is forensic, cultural twitches and evasions. It’s almost pastiche and almost satire and at times very funny. But it is also flexible. We move from being amused by the magpie Tama’s misinterpretations of the human social world, to being horrified by his factual observations of the inhumane things humans routinely get up to, especially on the farm, to being drawn into the lyrical yet cold and alien universe of the non-human.

Tama (not Indigenous, he points out, an incomer from Australia) falls from his nest and is rescued and nurtured by soft-hearted Marnie. Her husband Rob disproves of their deepening relationship, which distracts from what he feels ought to be the object of Marnie’s full attention: himself. He is the past champion in the Golden Axe wood chopping competition but feeling his age. Up against younger contestants such as the formidable Ethan Bloody McKay and Chin Scar, will he prevail? What are the implications for Marnie if he doesn’t?

Tama is an observant narrator, even if some of the customs of the human world escape his comprehension. He distrusts Rob, "watching me with his riverstone eyes like he was planning something, like he wanted to drive me up to the killing house where he drove the dog tucker sheep". He observes the interplay between husband and wife. He watches Marnie getting ready for bed and sees "down her white back, black. Green-black. Purple-black. Blue-black. Black-black." Rob is dangerous to both. The novel’s epigraph is from James K. Baxter’s poem, "High Country Weather":

Surrender to the sky

Your heart of anger.

But few of its characters do so.

*

Tama collects – as magpies are conventionally said to – random objects which he hides under the bath: Rob’s headache pills, a gold coin, a sucked-clean bone. But he also collects and deploys fragments of language from the human world around him: "Get in behind", "See how much you’ll save" "Here are the headlines". He watches a lot of television and sits with axeman Rob watching detective dramas about beautiful, mutilated dead women – ‘"This was no suicide, Trent. See the splatter patterns?"; "We have a DNA match, Trent. Let’s nail the lowlife scum and release the remains". These rhetorical tags become useful to Tama as the stagey violence of the screen bleeds into real life.

As their relationship develops and is elaborated, Marnie begins to post online images of Tama – playing with a clothes peg, wearing a pirate hat, a top hat, a nurse’s hat, bunny ears, dressed as batman, dressed as a wizard. Marnie’s family, even disapproving Rob, are amazed at Tama’s following: "all the faces, the tiny pictures of faces, piling up underneath me". Marnie, at first reluctant, is encouraged to monetise his celebrity. Crowds begin to arrive at the farm on Wilderness Road. "We’re not fucking Hobbiton", Rob snarls at two apologetic visitors, who explain their presence: "We are Klaus and Volker from Hamburg. We would like now to meet the bird who thinks he’s a person … Tama is enormous with German homosexuals".

Life with Marnie where he is cosseted, loved and celebrated necessarily entails Tama’s expulsion from the magpie world. "Stay away from us, keep out, keep out, this is our land and you are not welcome here", call his bird family. This is a general message of control of territory, but the humanised Tama is now seen as a particularly dangerous threat. "Sick sick sick", his wild sister warns her flock. "Don’t touch him and don’t let him in".

As I said, Chidgey’s skill as a writer persuades me to accept her non-human narrator, despite my pre-existing prejudice. But the other reason why this works in The Axeman’s Carnival is that it is a magpie who is doing the narration. These birds already come with a reputation for chat, but also with the weight of fable and menace. As Tama observes, in popular belief "we killed new lambs, we held the souls of gossips, we carried the devil’s blood in our mouths, we brought bad luck and sorrow and death, we laughed at the drowned world, we stayed silent at the crucifixion". Marnie may fashion Tama into a figure of cuteness and online appeal, but the menacing reality of the birds is a continuous underlying current – one of the many competing discourses we are invited to engage with. Denis Glover’s seemingly gentle ‘quardle ordle ardle wardle doodle’ actually means, in Tama’s translation, "Get out of here, get out get out, I’ll pierce your eyes and drink your blood and clean your bones".

In Chidgey’s telling, the magpie cosmos is complex and spiritually charged. In the morning, domesticised Tama is still aware of ‘the red sky the Sun-Woman kindling her campfire and my flock singing to greet her’. At night, "the ghosts of my brothers came in the peace and bloody quiet, and the ghost of my mother too, and they sang to me through the glass, their voices the wind on the pine trees, their voices in the rain, their voices in the swish and gnaw of something underground. And the ghosts of my brothers were only feathers, and the ghost of my mother was only bones. Death by car, they sang. Death by cold."

The Axeman's Carnival by Catherine Chidgey (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $36) is available in bookstores nationwide. It won the Jann Medlicott Acorn prize for fiction at the 2023 Ockham New Zealand national book awards announced on Wednesday night, and also won the informal category of the Reader's Choice Award when it was named the favourite New Zealand book of the year by ReadingRoom readers, announced on Wednesday morning.

Catherine Chidgey's next work of fiction, "Babydoll", a short story about a meth-head, will appear in ReadingRoom on Saturday.