Alice Palmer was an activist, author, educator and politician whose state Senate seat, after some controversy, served as the launching pad for the political career of Barack Obama.

In 1995, Mrs. Palmer announced she would give up her seat in Springfield and run in a special election to succeed convicted U.S. Rep. Mel Reynolds in Congress. She endorsed Obama as her chosen successor in the state Senate, but after she lost the congressional race to Jesse Jackson Jr., Mrs. Palmer decided to seek reelection to the state Senate.

Obama refused to halt his campaign, saying that he only entered the race because Mrs. Palmer had promised him she would not seek re-election. His supporters challenged Mrs. Palmer’s nominating petitions, causing her to withdraw and essentially end her political career. Obama won the seat.

“The elder Black community, people like civil rights activist Timuel Black, asked Obama to hold off because ‘Alice is senior, wait your turn,’ and they said, ‘No,’” Mrs. Palmer’s son, David Robinson, recalled. “It’s how fate turned things, and she never felt bitter about it.”

She may not have been bitter, but Cook County Circuit Court Judge Timothy Wright, a former attorney who counted Mrs. Palmer as a mentor, said she was bothered by how things panned out with her state Senate seat.

“I think she was upset. She felt that Barack had reneged on an agreement that they had,” he said.

Mrs. Palmer supported Hillary Clinton over Obama in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary, but did so because she was a feminist, and she saw Clinton as the practical choice, her son said.

The Clinton camp invited Mrs. Palmer, who served as a Clinton delegate from Illinois, to sit in the audience at a debate in Iowa, a move many interpreted as intended to rattle Obama.

“When reporters would call to ask her about this perceived feud, she would hand the phone to me, she never gave it a second thought, frankly. She was an intellect and never interested in any of that,” her son said.

Mrs. Palmer died May 25 from heart failure. She was 83.

Her political career may have drawn outsized attention, but it was just a chapter in a lifetime spent lifting up the lives of Black people in Chicago and around the globe.

Mrs. Palmer helped organize the anti-apartheid movement in Chicago in the 1980s and was arrested and charged with trespassing along with 16 others while marching in front of the city’s South African consulate. All 16 went to trial and were found not guilty by a jury.

“Not only that, the jury sent the judge a note to read aloud in court expressing their wishes to also join the Free South Africa Movement,” said Wright, who defended Mrs. Palmer.

During the protest that led to her arrest, Mrs. Palmer and others in the movement held an anti-apartheid poster aloft that she later presented to the South African President Nelson Mandela when he visited Chicago in 1993.

Mrs. Palmer grew up in Indiana. She attended Indiana University and moved to Chicago for higher education. She received a master’s from Roosevelt University and a doctorate from Northwestern University, where she co-authored two books on adult literacy and tutored at the university’s “Black House” — a longtime hub for African American student life.

“It was a place of refuge and mentoring and care, and she helped move students along and become successful,” her son said. She referred to a number of Black students who went on to make waves in various professional careers as her “Black House babies,” her son said.

Her husband, Buzz Palmer, who passed away in 2021, was her partner in activism. He had served in the Air Force, where he learned to speak German and his duties included monitoring radio communications in East Germany and behind the Iron Curtain. He went on to become a Chicago police officer who co-founded Chicago’s Afro-American Patrolmen’s League in 1968.

The pair met when Mrs. Palmer worked briefly as a teacher at Malcom X College, where Buzz Palmer worked as head of security and interceded on her behalf with an unwanted suitor.

They held the first fundraiser for Harold Washington’s historic 1983 campaign at the kitchen table of their South Shore home, Robinson said.

Mrs. Palmer’s husband went on to head Chicago’s Sister Cities program during Washington’s administration, allowing the couple to connect with people around the world who saw the Black struggle in the U.S. as an impetus for change.

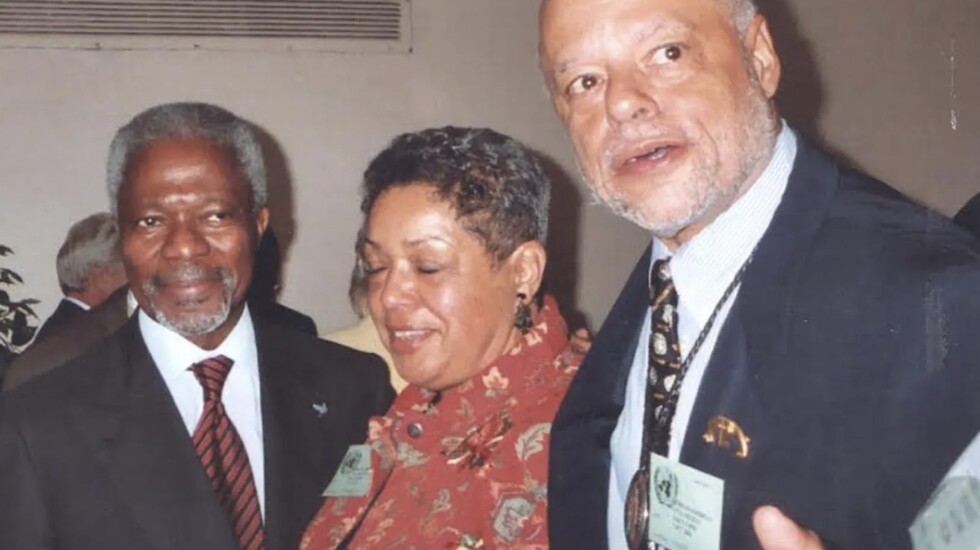

The couple also co-founded the Black Press Institute and helped start an international news digest, the Black Press Review. They helped organize gatherings for Black journalists to meet newsmakers, including United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

“Mom was beloved by family, comrades, her hundreds of friends and the community,” her son said.

Mrs. Palmer loved classic movies, BBC mysteries and collected antique teddy bears.

In addition to her son, she is survived by her daughter, Zella Palmer, and stepdaughter Lisa Palmer, as well as seven grandchildren and one great grandchild.

A memorial is being planned.