According to a legend, more than two centuries ago, a famous Paris astronomer used to stand on one of the Seine bridges on nights when the variable star Algol was in eclipse, to point out this remarkable phenomenon to passersby.

Today, more than 27,000 Algol eclipses later, the periodic brightness changes of this star remain a fascinating sight to the amateur who knows when to look and what to look for. Algol, in the constellation of Perseus, the Hero, was known since ancient times as "The Demon Star" and is one of the most famous variable stars in the sky.

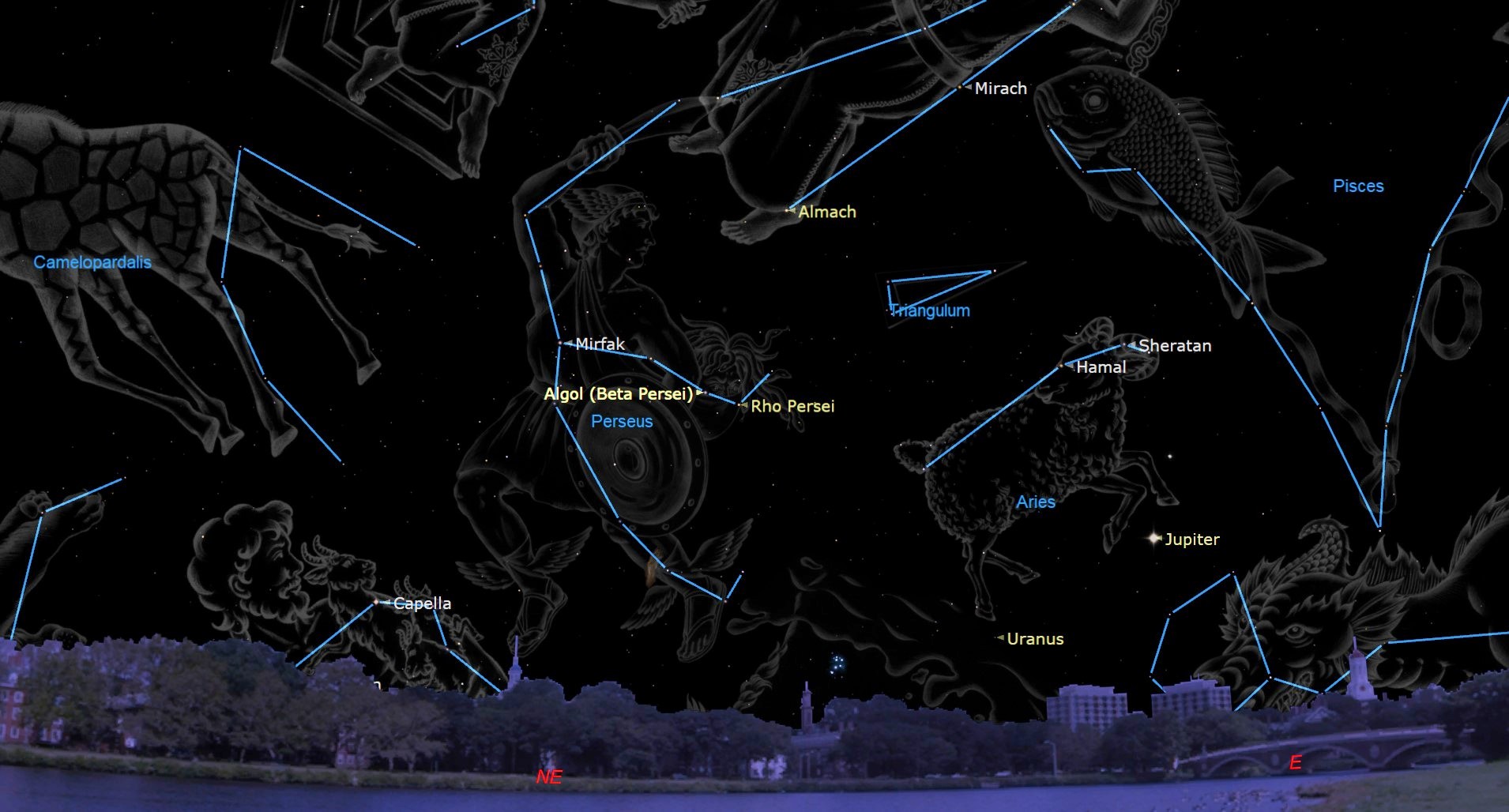

Normally, Algol appears 3.3 times brighter than during the peak of the eclipse; it usually shines at magnitude 2.1, about equal to the star Almach (Gamma Andromedae), but at intervals of 2.867 days, when it's at minimum light, it fades to about magnitude 3.4, or about equal to Alpha Trianguli, a binary star in the constellation of Triangulum. While its diminished light lasts nearly 10 hours, the eclipse begins and ends so gradually that most of the fading and subsequent brightening takes place within the two hours before and two hours after mid-eclipse.

Related: Night sky, November 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

This week, Algol can be found almost directly overhead at around 11 p.m. It spends the rest of the night, slowly descending down into the northwest sky, and will be quite low to the northwest horizon by around the break of dawn. To see it, find the Perseus constellation; Algol makes up one of the "eyes" of Medusa's head that Perseus carries. If you're unfamiliar with Perseus, a stargazing app can help you locate it.

The Demon

Want to see Algol up close? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

In the sky, Perseus is a pattern of stars that can be visualized in different ways. Some see it as a large starry arrowhead that points upward along the Milky Way toward the distinctive 'W' of Cassiopeia. Others might see him resembling a lopsided letter 'K' with the downward side of the K pointing to the Pleiades, while the upward arm ends with the star Algol, the Demon, a famous prototype variable star. Its name derives from Ra's al-Ghul, Arabic for "the demon's head," according to an expert in star nomenclature, the late George A. Davis, Jr.

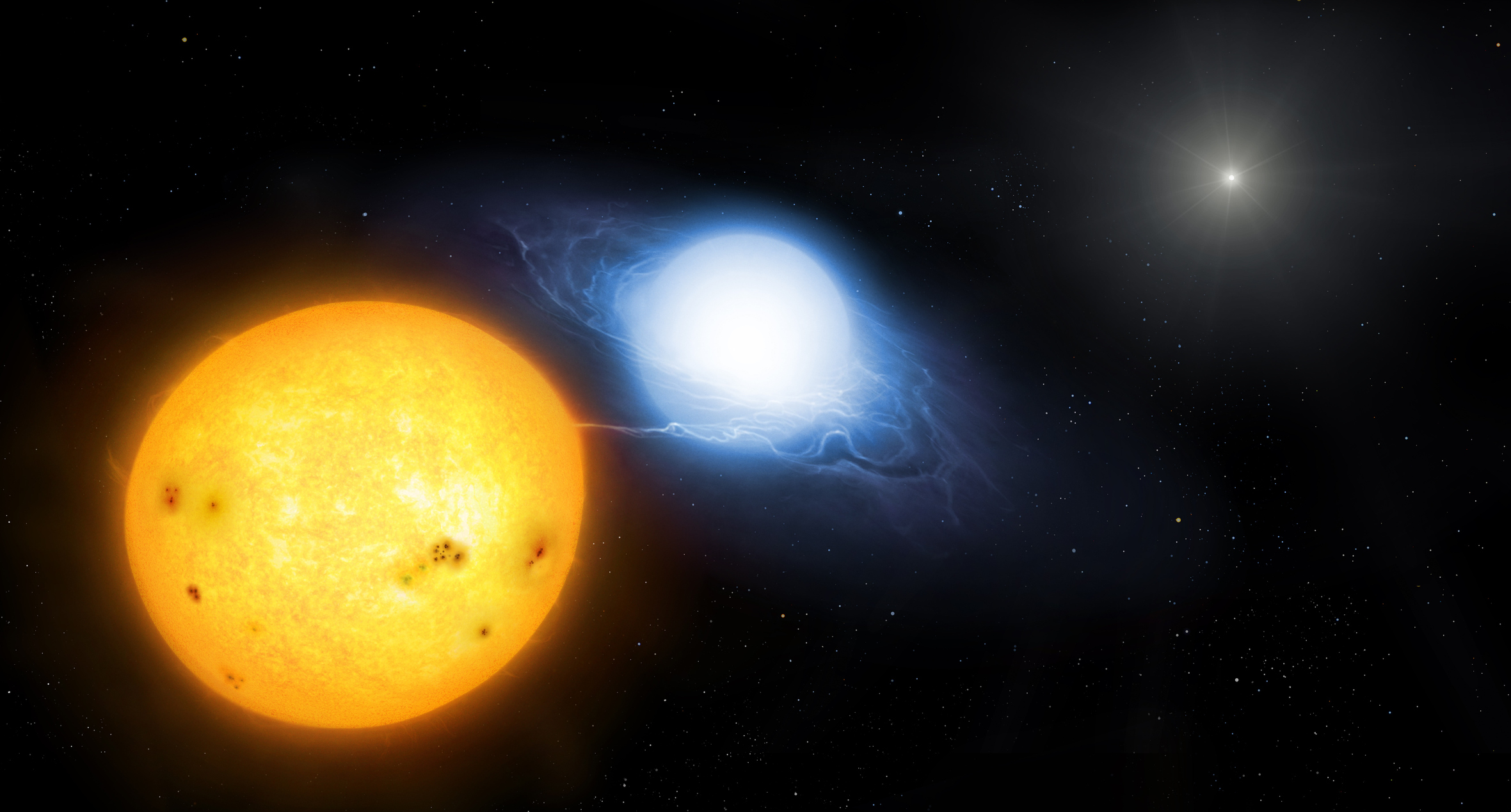

Although we call Algol a variable star, it does not intrinsically brighten and dim because it expands and contracts (like the star Mira). Rather, its light changes result from the eclipse of one binary-star component by another, because their orbital plane lies nearly in our line of sight.

Algol is about 90 light-years away. The two components are about the same size but unequal in luminosity. The slightly smaller, blue star is about 90 times as luminous as the sun and brighter than its orange companion, and when it passes behind the latter, the total light of the system fades greatly. The orange star is "dim" only in comparison to the bright star; it gives off about three times the sun's light.

Fluctuations first noted 3½ centuries ago

Algol has a long and venerable history. It's the most prominent eclipsing variable star in the sky and the first discovered. The first astronomer who first noticed Algol's fade-downs was Geminiano Montanari of Bologna, Italy around 1667. At that time the only other variable star known was Mira, whose light varies over months instead of hours.

Perhaps this is why few other astronomers paid much attention to Montanari's discovery. Algol's variability was rediscovered in 1782 by an 18-year old English amateur John Goodricke. He observed the star systematically and determined its period and correctly suggested the reason for the variations: A dim body orbits the star, periodically blocking some of its light from our view.

Eclipses this week

In the table below are predictions of when Algol will shine at minimum brightness (mid-eclipse) during this upcoming week. Naked-eye and binocular observers can watch Algol dim and recover. Though each primary eclipse lasts about 9 hours 40 minutes as the star fades from magnitude 2.1 to 3.4 and recovers, most of the light change takes place from about three hours before to three hours after minimum; it's at minimum for about 10 or 12 minutes.

(An asterisk (*) next to the time in the row designated for Nov. 19, indicates that because minimum occurs before local midnight, the calendar date for the Pacific Time Zone is Nov. 18.)

Did the ancients notice?

As I mentioned earlier, the first definitive observation that revealed that Algol varied in brightness was by Geminiano Montanari in 1667. Still, was Montanari really the first? For many centuries prior to Montanari Algol represented one of the eyes in the head of Medusa held by Perseus in the allegorical outline of the constellation. The literal translation of Algol means, "The Mischievous One." And ancient and medieval astrologers considered Algol the most dangerous and unfortunate star in the heavens.

So, was Algol's strange variability noticed in antiquity? Notes Robert Burnham Jr. in his Celestial Handbook: "This reasonable conjecture remains unsupported by any other real evidence." On the other hand, a paper published in 2013 in the Astrophysical Journal by a team of researchers, suggests that a calendar for lucky and unlucky days composed in Egypt 32 centuries ago, indicates a distinct periodicity of 2.85 days suggesting that this periodicity might indeed be connected to Algol.

If you want to get an up-close look at Algol or the many fascinating sights of the Perseus constellation, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you're looking to take photos of Algol or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to shoot the night sky, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.