ACTOR, dancer, singer, writer, cabaret performer, raconteur, political activist (not least for LGBTQ+ rights and Scottish independence) – the list of Alan Cumming’s skills and accomplishments is as impressive as it is prodigious.

Now, at the age of 57, he is about to add “solo dance-theatre performer” to his shining CV. In collaboration with award-winning choreographer Steven Hoggett (who is, perhaps, best known to Scottish audiences for his work on Black Watch), Cumming is creating Burn, a choreographed work reflecting on the life of our national Bard, Robert Burns.

When I catch up with the star of The Good Wife he is working in Vancouver, Canada. Burn, he tells me, is a consequence of a serendipitous collision of two quite unrelated things.

On the one hand, he was contemplating the possibility – as a man in the later years of middle-age – of taking on another dance piece. Then an offer came in that brought that idea together with his fascination with Burns.

“It all started when I did Cabaret [the famous musical set in Weimar Germany] on Broadway the last time. It finished in 2015, I was 50, and I just sort of felt like this was it: I’d never be this fit again, I’d never be asked to do anything like this again.

“I was right, it would be normal for that to be the case. It was kind of freakish that I was even doing that level of dancing in that show at that age.”

This sense of his career reaching a significant moment of transition focused Cumming’s mind, he remembers. “I thought, ‘I still have one more thing in me.’ I kind of put that out to the universe that I wanted to do another dance thing.”

Which is not to say that the “thing” he had in mind was Burn. In fact, he explains, whatever he was thinking the prospective dance project might be, “I was not at all thinking it would be a solo dance-theatre piece.”

It just so happened, the actor tells me, that, soon after his post-Cabaret yearning to do another choreographed show, the Joyce Theater in New York asked him if he would like to make a dance-theatre work. This invitation planted a seed in his mind, leading to an all-important conversation with Hoggett.

“I was thinking about doing something about Burns,” says Cumming. “I wanted to find out more about the man behind the myth.”

To cut a long story short, Cumming’s original idea of doing some kind of show about Scotland’s Bard grew like Topsy, drawing in the National Theatre of Scotland (NTS) and the Edinburgh International Festival as co-producers with the Joyce. Before the actor knew it, his vague notion of making a piece about Burns had become, he says with a laugh, “this one-man dance-theatre piece”.

As co-creators, Cumming and Hoggett have been engaged, not only in intensive artistic development, but also a considerable amount of biographical and historical research. “We’ve worked on it a lot in workshops,” the actor says, “and talked with all these academics at Glasgow University.”

The project that emerged from all of this activity was set for a 2021 premiere. However, as Burns had it, “the best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft a-gley”.

The Covid pandemic conspired to push the show’s opening back. Now, as we finally stumble towards some sort of normality, Burn is finally making its debut performances in Scotland, beginning with preview performances at the Beacon Arts Centre in Greenock, before transferring to the King’s Theatre during the Edinburgh International Festival.

Cumming’s excitement about the project is palpable. “I’ve always wanted to dance more,” he says.

“I really admire dancers,” he adds. He dislikes the confines that often characterise professional dance. The notion “that you’ve got to do dance in a certain way”, is, he says, “restricting how people communicate through dance and movement”.

“So, I’m really excited when people like Steven come along and they make up choreography that comes out of your body. It’s not a form put upon you.

“That is really exciting to me. Also, as an older person, I feel like I’ve got more to say, and I’ve got a form that I can move in, that’s going to come from whatever I can do with my body.”

If Cumming is thrilled by the mutual artistic compatibility he shares with Hoggett, he’s equally enthusiastic about the idea of exploring Burns from such an unusual perspective. “If I’m going to look at Burns, and ask people to look at Burns, in a way that’s different to what they’ve been used to, maybe it’s best that I do it in a form that I’m not used to, and people aren’t used to seeing me in.”

Dance-theatre is, first-and-foremost, about expressing emotional and psychological states, rather than telling a straightforward narrative. So it is with Burn.

That has required Cumming and Hoggett to get to grips with the man Burns was, rather than simply the poetic voice we all know. To that end, the pair have focused primarily on the poet’s letters.

“The interesting thing when you go to the letters,” says the actor, “is that he doesn’t speak like you normally hear him, because he’s not writing in Scots. I realised that it was a choice for him to write his poems in Scots. It’s an artistic choice, of course, but also a socio-political choice.”

Indeed, Cumming continues, reading Burns’s letters is like reading “a completely different person” from the man who wrote the poems. Immersing himself in the Bard’s letters was “fascinating”, the actor continues. “You learn so much about him and what his life was like.

“He had a short life, and a very tragic life. He dealt with poverty throughout his life. He had to write all these begging letters to patrons. He had to become this obsequious sort of person, just trying to survive.”

The tribulations of Burns’s life combine with his famously radical politics in ways that speak to Scotland in the 21st century, Cumming believes. “He talks about independence a lot.

“Obviously, we talk about it a lot now. But, as soon as I bring up that word ‘independence’, it’s tightened sphincters all round, because it’s so politicised… “Burns talks about independence for Scotland a little bit, but, mostly, he talks about independence of mind, and that he wants independence of means for his children. The idea of independence and self-determination is very ingrained in him, and very ingrained in Scottish history.”

Cumming is wary of being considered a narrowly polemical artist. “It feels like you’re making a political statement [when you raise Burns’s pro-independence views],” he comments.

“Of course, I am [making a political statement],” he adds. “But I don’t feel that I’m doing that without cause, because it’s there to see in our history and in Burns’s life.

“The values he espouses are values that we think of as completely Scottish values, about justice, egalitarianism and self-esteem. There wasn’t really a word for it when he wrote A Man’s A Man For A’ That, but, basically, that’s a poem about self-esteem.”

Through his exploration of Burns’s letters, Cumming has been moved, not only by the “shadow of poverty” that is cast constantly over the poet’s life, but also by the tragedies he faced. “Such terrible things happened to him,” says the actor.

“The person we know of as ‘Highland Mary’ died just before [she and Burns] were probably going to go to the West Indies together”, he comments. Then, of course, there was the death in infancy of six of the nine children that Burns’s wife, Jean Armour, bore him.

“A lot of his children died,” says Cumming. Indeed, the actor adds, even if the infant mortality rate in Burns’s day was high, “that doesn’t make it any less awful”.

“He seems like a really tender father. He talks about his kids running around his desk when he’s writing.”

As if these sufferings were not enough, Burns was injured regularly throughout his life. “He kept falling off horses, or having carriages banging into him,” says Cumming.

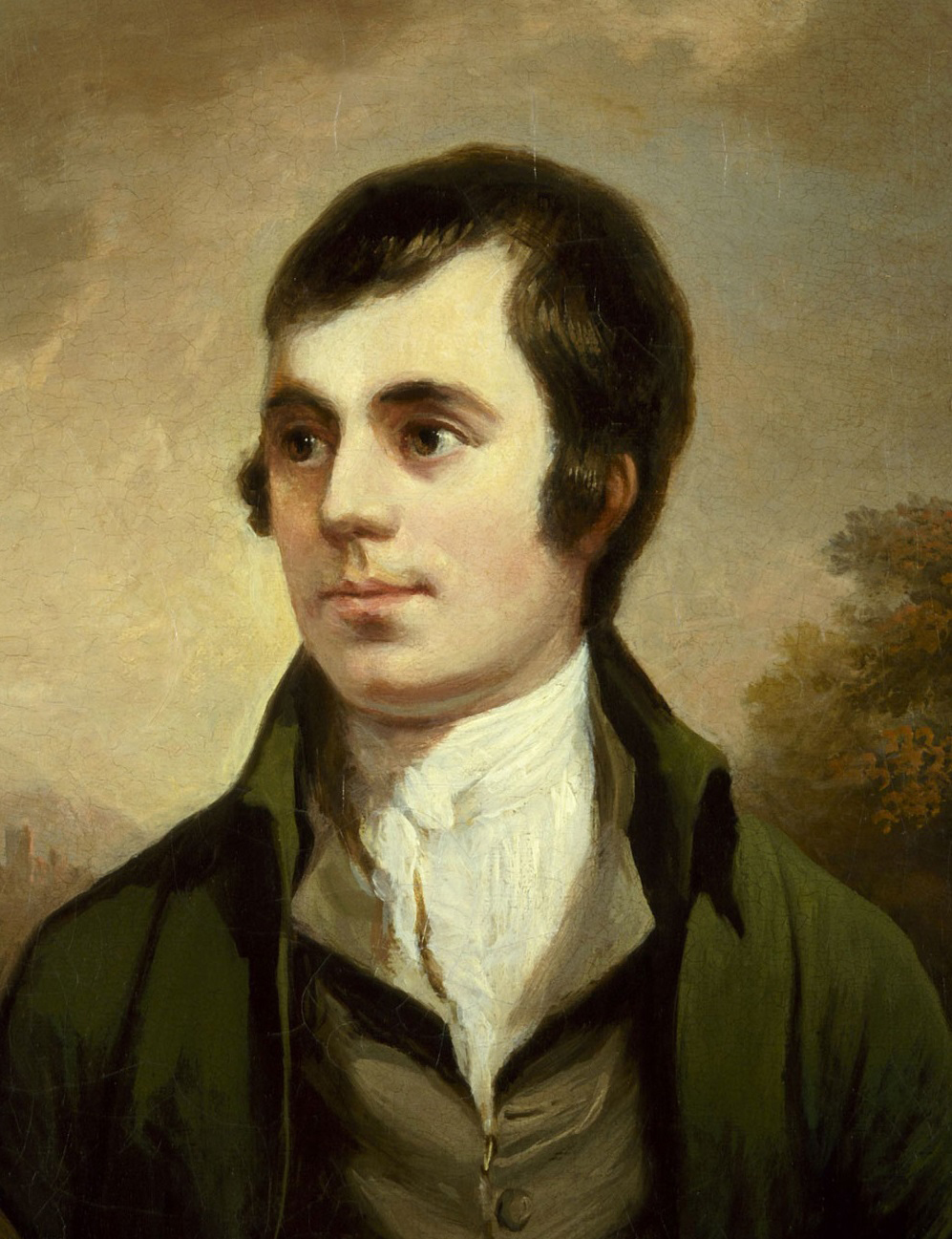

We can often think of Burns as a virile son of the soil. Indeed, he appears so in Alexander Nasmyth’s famous 1787 painting, in which the poet appears handsome and in rude health.

In reality, as Cumming points out, Burns suffered failing health and a dreadfully early death, at the age of just 37. “He was such a fragile thing,” the actor says. “He seems so robust to us, but he wasn’t.”

Even when Burns enjoyed success, as he did in his time in Edinburgh, he still suffered privations, Cumming observes. “The adulation was mixed with the fact that he was a bit of a minstrel. He was made to dress up in his ploughman’s gear and be the working-class hero. He was also injured there, and he got very depressed in Edinburgh.

“He loved meeting Lord and Lady Blah Blah initially, and then [the novelty] wore off.”

Ultimately, the actor comments, Burns cut a sad, lovelorn figure in Edinburgh. “Every good thing [in his life] was tinged with sadness.”

In fact, Cumming suggests that, in the language of modern mental health, our national poet would be considered to have suffered from bipolar disorder. “It’s not even controversial [among Burns experts] to think that. It’s well documented,” he says.

In the actor’s opinion, Burns’s “bipolarity is almost a metaphor for his life. Even his great success didn’t give him the financial security that he needed”.

Take the great collection of Scottish songs that Burns collated and edited, for example. “It was a great legacy that he left us,” Cumming comments, “but he didn’t receive anything in return for it [financially].”

As a dance-theatre piece reflecting on this life, Burn will not offer a linear narrative, says the actor. “It’s more impressionistic… It’s about his life and what happened to him, but I’m not reciting any of his poems or singing any of his songs.”

Rather, Cumming will offer audiences, “physical manifestations of how I think Burns would have been feeling”.

He and Hoggett are building the piece from scratch. It’s a way of working that Cumming finds “utterly exciting… I’ve never really done any devised shows,” he says, “let alone a dance one.”

The actor is delighted to be previewing Burn in Greenock, before transferring to the Edinburgh International Festival. From there, the piece will tour around Scotland before heading across the Atlantic.

“It’s the second show I’ll have done for the NTS where we’ll have gone from Inverness to New York,” he says with a grin.

You can’t help but feel that the Bard himself would have saluted the production’s grand ambition.