Alan Arkin, the wry character actor who got his start with Chicago’s Second City troupe and won an Oscar in 2007 for “Little Miss Sunshine,” has died. He was 89.

His sons Adam, Matthew and Anthony confirmed their father’s death through the actor’s publicist on Friday. “Our father was a uniquely talented force of nature, both as an artist and a man,” they said in a written statement.

After his stint as a member of the Second City comedy troupe, Arkin went on to immediate success in movies with the Cold War spoof “The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming” and peaked late in life with his win as best supporting actor for the surprise 2006 hit “Little Miss Sunshine.”

More than 40 years separated his first Oscar nomination, for “The Russians are Coming,” from his nomination for playing a conniving Hollywood producer in the Oscar-winning “Argo.”

In recent years, he starred opposite Michael Douglas in the Netflix comedy series “The Kominsky Method,” a role that earned him two Emmy nominations.

Arkin once joked to The Associated Press that the beauty of being a character actor was not having to take his clothes off for a role. He wasn’t a sex symbol or superstar but was rarely out of work, appearing in more than 100 TV shows and feature films including “The In-Laws.”

His trademarks were likability, relatability and complete immersion in his roles, no matter how unusual, whether playing a Russian submarine officer in “The Russians are Coming” who struggles to communicate with the equally jittery Americans, or standing out as the foul-mouthed, drug-addicted grandfather in “Little Miss Sunshine.”

“Alan’s never had an identifiable screen personality because he just disappears into his characters,” director Norman Jewison of “The Russians are Coming” once observed. “His accents are impeccable, and he’s even able to change his looks. ... He’s always been underestimated, partly because he’s never been in service of his own success.”

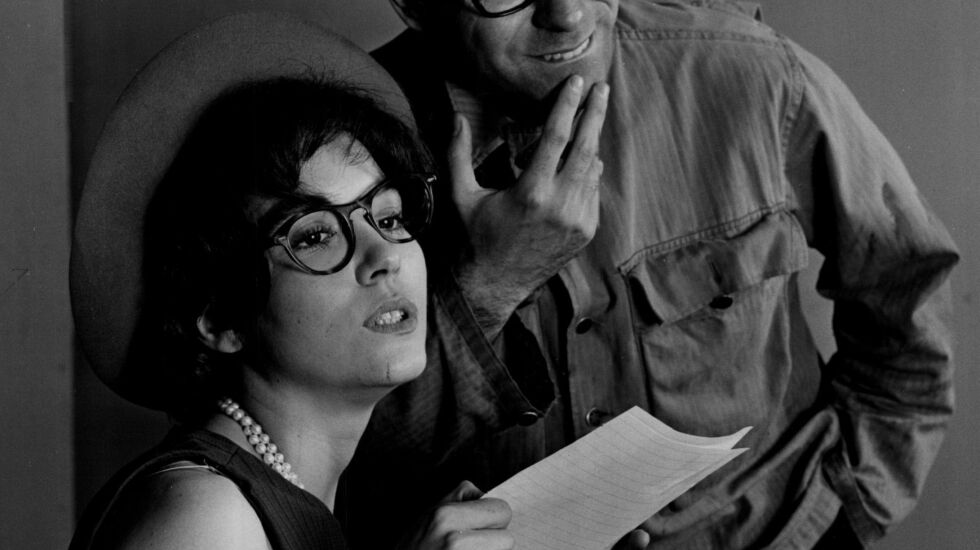

While still with Second City, Arkin was chosen by Carl Reiner to play the young protagonist in the 1963 Broadway play “Enter Laughing,” based on Reiner’s semi-autobiographical novel.

He attracted strong reviews and the notice of Jewison, who was preparing to direct a 1966 comedy about a Russian sub that creates a panic when it ventures too close to a small New England town.

In Arkin’s next major film, he proved he also could play a villain, however reluctantly. Arkin starred in “Wait Until Dark” as a vicious drug dealer who holds a blind woman (Audrey Hepburn) captive in her own apartment, believing a drug shipment is hidden there.

He recalled in a 1998 interview how difficult it was to terrorize Hepburn’s character.

“Just awful,” he said. “She was an exquisite lady, so being mean to her was hard.”

In 1968’s “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,” he played a sensitive man who could not hear or speak, which again elevated Arkin’s status in Hollywood.

He starred as the bumbling French detective in “Inspector Clouseau” the same year, but the film would be overlooked in favor of Peter Sellers’ Clouseau in the “Pink Panther” movies.

Arkin’s career as a character actor continued to blossom when Mike Nichols, a fellow Second City alumnus, cast him in the starring role as Rossarian, the victim of wartime red tape in 1970’s “Catch-22,” based on Joseph Heller’s best-selling novel.

Through the years, Arkin turned up in such favorites as “Edward Scissorhands,” playing Johnny Depp’s neighbor, and in the film version of David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross” as a dogged real estate salesman.

He and Reiner played brothers, one successful (Reiner), one struggling (Arkin), in the 1998 film “The Slums of Beverly Hills.”

“I used to think that my stuff had a lot of variety, but I realized that, for the first 20 years or so, most of the characters I played were outsiders, strangers to their environment, foreigners in one way or another,” he told The Associated Press in 2007.

“As I started to get more and more comfortable with myself, that started to shift,” Arkin said in that interview. “I got one of the nicest compliments I’ve ever gotten from someone a few days ago. They said that they thought my characters were very often the heart, the moral center of a film. I didn’t particularly understand it, but I liked it. Iit made me happy.”

Other recent credits included “Going in Style,” a 2017 remake featuring fellow Oscar winners Michael Caine and Morgan Freeman, and the TV series “The Kominsky Method.”

Arkin also directed the film version of Jules Feiffer’s 1971 dark comedy “Little Murders” and Neil Simon’s 1972 play about bickering old vaudeville partners, “The Sunshine Boys.”

On television, Arkin appeared in the short-lived series “Fay” and “Harry” and played a night court judge in Sidney Lumet’s drama series “100 Centre Street” on A&E.

He also wrote several books for children.

Born in Brooklyn, he and his family, which included two younger brothers, moved to Los Angeles when he was 11. His parents found jobs as teachers but were fired during the post-World War II Red Scare because they were Communists.

“We were dirt poor so I couldn’t afford to go to the movies often,” he told the AP in 1998. “But I went whenever I could and focused in on movies, as they were more important than anything in my life.”

He studied acting at Los Angeles City College, California State University, Los Angeles and Bennington College in Vermont, where he earned a scholarship to the formerly all-girls school.

He married fellow student Jeremy Yaffe, and they had two sons, Adam and Matthew.

After he and Yaffe divorced in 1961, Arkin married actress-writer Barbara Dana, and they had a son, Anthony.

All three sons became actors: Adam Arkin starred in the TV series “Chicago Hope.”

“It was certainly nothing that I pushed them into,” Arkin said in 1998. “It made absolutely no difference to me what they did as long as it allowed them to grow.”

Arkin began his entertainment career as an organizer and singer with The Tarriers, a group that briefly rode the folk musical revival wave of the late 1950s. Later, he turned to stage acting, off-Broadway, in dramatic roles.

At Second City, he worked with Nichols, Elaine May, Jerry Stiller, Anne Meara and others in creating intellectual, high-speed impromptu riffs off the fads and follies of the day.

“I never knew that I could be funny until I joined Second City,” he said.