Initially influenced by the likes of experimental hip-hop artists such as cLOUDDEAD and Odd Nosdam, Rob McAndrews had already began producing prior to being invited to play guitar as a touring musician for childhood friend James Blake.

Quick to find his own unique sound palette, McAndrews’ brooding debut album For Years (2013) had an analgesic yet idiosyncratic quality, rich with discordant acoustic guitars and edgy hip-hop beats.

Fast-forward eight years and little had been heard from McAndrews, save for a few singles and EPs, and 2021’s otherworldly acoustic-electronic LP And a Bit of Hope. However, Airhead’s third LP Lightness charts a distinctive yet no less inventive course.

Studying the techniques of numerous American jazz guitar greats, McAndrews discovers ingenious ways to process the instrument, combining tightly packed chord fragments with microscopic beats and deep sub-bass.

Your previous LP And a Bit of Hope and much of your early work blends guitars with electronics. Was guitar therefore your initial instrument?

“I started learning piano when I was five because my mum was training to become a piano teacher. Soon after, I saw someone playing cello and became enamoured with the sound of that, so I began playing cello from around seven years old, and it became my main instrument after I stopped with the piano a few years after. Then I got an electric and an acoustic guitar, became obsessed with early folk music and spent a lot of time copying the fingerpicking styles of people like Mississippi John Hurt, Blind Blake and Reverend Gary Davis.”

You also play guitar on stage for James Blake. What led to that chain of events?

“James and I grew up together and were making music from our early teens. I was at Leeds College of Music studying music production and he went to Goldsmiths to do a popular music course, but we stayed in touch throughout. He’d made an album as his final year project and needed to perform it live, so we sort of got a stripped down version of the ‘band’ back together again and haven’t stopped playing shows since. It’s been very enlightening to play a role in performing his music to crowds around the world – it’s a chance to see first-hand the emotional impact that music can have on people, and what works most effectively in creating those important moments.”

When did you start recording your own material?

“After the guitar music, I got really into a corner of rap music made by people like Cannibal Ox and cLOUDDEAD. Around that time I got a multi-track recorder and a Boss Dr Sample SP-202 because I wanted to make stuff like Odd Nosdam. Combining slowed, pitched-down, degraded samples and over-compressed breaks had a huge influence on my productions.”

Your sound design has always been very intricate. We read that one of your ambitions from the start was to create some sort of 3D sound image...

“My main drive has, and I hope always will be, to try and create something that sounds unique. As a teenager, I would almost exclusively listen to music on headphones with my eyes closed, and loved hearing sounds and ideas appear in different parts of the stereo field, so I became heavily focused on placing sounds into some sort of 3D soundstage, and moving them around in intricate ways.”

What did you learn from Edgar Varèse’s musings on composition?

I feel more of a connection to a track I'm building if the samples or sounds are personal to me

“My main takeaway was his philosophy that music is organised sound, and therefore all sounds, whether environmental or deliberately designed, can be worked into compositions. His spatialisation of sound by placing performers in unusual configurations in order to achieve an unusual soundstage influenced my focus on placing sounds in the stereo field, and tucking little Easter eggs into the background of tracks.”

Was there a turning point when you felt you had begun to form your own identity?

“A turning point was examining my own musical history and asking myself how I could combine my influences and limited experience into something unique. From there, it was a case of introducing guitar recordings, resampling those alongside bits of cello, and drawing on samples from records that meant a lot to me, as opposed to things I might find in sample packs.

“By combining them with slightly more esoteric production techniques and trying to make tracks that a DJ like Ben UFO might play in a set, I eventually ended up with a sound that I’d hoped to be considered relatively unique. There was a more recent turning point when I decided to study and learn new things on the guitar, and it was during the making of Lightness that I noticed how stimulating learning new things can be for the creative process.”

What sort of new things did you teach yourself?

“I wanted to expand my harmonic vocabulary, so I started studying guitar books like Ted Greene’s Chord Chemistry, Barry Harris’ Harmonic Method for Guitar, Joe Pass’s Guitar Chords and Mick Goodrick’s The Advancing Guitarist. Studying these helped me to break free from the voicings and habits I’d picked up, and record new ideas that piqued my interest. I would then process these chords, whether it was rolling off the attack of each chord to make the guitar sound more synth-like or capturing them through modular processing.

“Rolling off the attack created the sounds you can hear on album tracks like Break In and Unbearable Lightness, whereas recording chords into the Instruo Arbhar granular audio processor can be heard on Low Gravity and Still Waiting For U. In fact, the acoustic guitar on Low Gravity was recorded using the Arbhar’s in-built condenser mic, so all the background noise is granulated too creating a really nice texture. With regards to the drums, I’d previously released a track called Nothing Feels Like Anything where I’d used a drum palette that didn’t have any low-end and ended up developing that sound further on Lightness.”

You’ve stated that you need to find emotion in the sounds you choose. Can you expand on that?

“I feel more of a connection to a track I’m building if the samples or sounds are personal to me. For example, when a fragment of vocal comes in, it appears with the memories and connotations I had with the original track, which draws me into the idea more and influences the sounds I layer it with, whether that’s a specific synth, chords or drum sounds. When I’m connected to the sounds that are being organized, it just makes me care more and feel more.”

At some point you moved entirely into the box?

“The first software I had was eJay Hip Hop, which didn’t result in me making any interesting music, so I moved onto Logic Pro 7 and started learning its many secrets. Nowadays, I’m using Ableton Live, and Logic for things like vocal comping – because I haven’t taken the time to figure out how to do that in Ableton yet. I work from home and in some ways my studio is less professional than it used to be, which may be an unconscious influence from some sessions I did with Brian Eno.”

So these days you’re primarily working in the computer alongside some specific hardware?

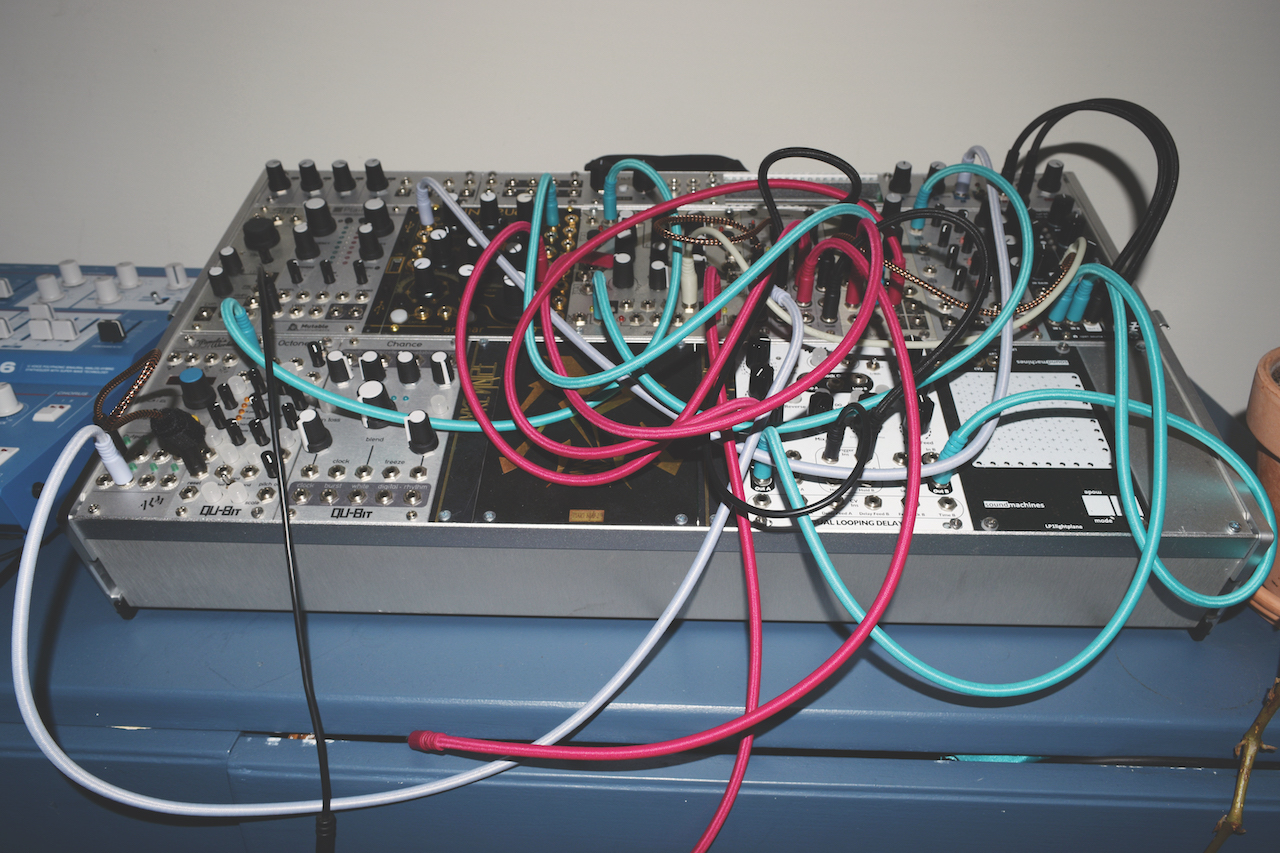

“I run my Fender Telecaster and Neumann TLM 103 into a Neve 1073LB and often route the guitars from the preamp into my modular setup, which I’ve managed to keep relatively constrained. It’s all kept in an Intellijel 104hp 7U performance case and the combination of modules changes depending on the patch. I’ll record a long jam, often incorporating the Instruo Arbhar, Batumi, Three Sisters, Dual Looping Delay and Clouds and then chop fragments out of that; or just drop the whole thing into Ableton Simpler and start playing slices on a MIDI keyboard with other effects running on top.

“I also recently bought an UDO Super 6 Desktop, which I play using an Arturia Keystep Pro. The Keystep Pro is also used to play and sequence an STO synth module and Mutable Instruments’ Plaits in the modular setup. Most of my detailed work is done on a pair of Sony MDR-7520s, which are great, but one of the ears squeaks when I turn my head, which is a bit annoying.”

Apart from the gorgeous melodies, the first thing we noticed about Lightness’ opening track, Break In, was the deep, resonant sub-bass…

“It’s a clean sine wave sample played by Ableton’s Simpler with no EQ or compression on it, but I did get into the ‘controls’ section of the Simpler and used a slow attack (1.84s) to affect the pitch by 17.8% at a rate of 4.05Hz, so the notes wobble around a bit if they’re sustained long enough. Sometimes I feel these subtle differences can have an important psychoacoustic impact and help stop the music from feeling too repetitive.”

A lot of the sounds you use are very delicate and detailed. What interests you about that approach?

“I suppose it must reflect my personality in some ways – I like to escape and get lost in things. I discovered chess in the past few years, and have dedicated far too much time to learning it. It appears that the same trait is apparent in the music I’ve made, because I like things to be as close to perfect as I can make them and feel uneasy when they’re not.”

When it comes to balancing sounds, is it all done by ear, or is there a level of spectral analysis involved?

“I spent years focused on fine-tuning EQ and compression, but I’ve recently become a lot more heavy-handed with my processing – for example, picking a synth sound that is high and clear if the rest of the beat is dominating the lower frequencies or picking the right drum samples in the first place. I do end up using the FabFilter Pro-MB if frequencies are poking out, especially if it’s something like an acoustic guitar recording from an iPhone.

“That goes against everything I was initially taught about using my ears, but the spectral analysis meter that comes up makes it so quick to tame the right frequencies. I also use the FabFilter Pro-Q 3 for broad stroke EQing – boosting all the highs or cutting all the lows, etc. Right now I’m using Ableton’s built-in compressor for pretty much all my compression and rarely change anything more than the threshold, occasionally venturing into the attack and decay times.”

Rather than use traditional beats, kick or snares, you seem to use tiny fragments of those sounds. How are you achieving that?

“Using fragmented samples without any low frequencies was another big breakthrough for me. I’ve been using FXpansion’s Geist plugin for drums for the past few years as it’s so quick to programme, manipulate samples, add swing and control the velocity of individual hits. Most of the single hits were drastically shortened so they’re only milliseconds in length, and pitched up an octave or thereabouts depending on the sound.

The main takeaway from the sessions with Brian Eno was that the idea should always take precedence over technology

“I’ve also been trying to get used to Ableton’s Drum Rack, but it hasn’t quite gelled for me yet. I’ll occasionally use Native Instruments’ Transient Master on the whole drum channel, with the sustain set very low and attack pushed up a little bit. A more extreme version of that is the BOZ Digital Labs Transgressor, which is more powerful but sometimes a bit overkill if pushed too hard.”

Towards the end of the track Ghosts in CS, there appears to be a lot of clashing, overlaid harmonic frequencies. It shouldn’t work, but it does...

“I was hoping to make that section sound as explosive as possible, so it’s a couple of synths playing different voicings of the same chords on top of each other. One of the synths was my friend Matt Walker’s (aka Julio Bashmore) Yamaha CS-60 and the other is Native Instruments’ Massive. Both are heavily side chained to a muted drum channel playing the main beat.

“I think the depth comes from the CS-60’s imperfections; the oscillators slowly wheeze out of tune and back again and create such a beautiful chaos when coupled with the noise generator and white noise channel of Massive, where I add a small amount of a slow LFO on the oscillators’ pitch to make everything sound more alive. I think the CS-60 is the best synth I’ve ever used, although I haven’t been lucky enough to try a CS-80 yet. The oscillators sound thick and incredible, and using aftertouch to detune them creates these beautiful, Boards of Canada-esque sounds.”

Do you have any fave plugins or other cool gadgets for sound design?

“A lot of the processing for this album came from either Permut8 effects plugin or Melda Production’s MRhythmizer, which is great for feeding ideas into and generating unusual rhythmic ideas. I also really like the free Michael Norris plugins for strange sounds. I’ll put the effects directly on an audio channel and record the output of that into a new track and chop the results up.

“I’ve also been using Aberrant DSP’s SketchCassette recently as it’s relatively cheap and adds some nice hiss and textures to tracks. On the track Salt, I used a coin to play the second melody with loads of reverb – Valhalla Room verb – by muting the strings with my left hand and rubbing a coin that has a slightly serrated edge lightly over the frets.”

You mentioned working with Brian Eno earlier. We have to ask, how did that come about?

“That all happened when James was in the middle of making his second album, Overgrown. We had the option to do some stuff with Brian Eno, and I was very excited to be involved. We recorded the early stages of a song called Portland, which is still yet to see the light of day, and developed a track that James had already started on an OP1 called Digital Lion. James was at the helm, and Brian Eno would disappear for a few minutes and come back with exotic guitars for me to try.

”I suppose the main takeaway from those sessions with Brian was that the idea should always take precedence over technology. From what I remember, the equipment we were using wasn’t anything particularly special and the space wasn’t so much a studio as a small room in an old architect’s studio in West London.

”During breaks we’d drink decaffeinated tea and at one point Brian put on a vinyl copy of Reverend James Cleveland’s Peace Be Still and got us to sing along. It was a memorable moment, even if I was silently mouthing along while James and Brian did the singing. Brian was into the idea of people singing together as a choir, no matter their ability. I suppose it’s a nice bonding experience – something to bring people together in an era where we’re so often sat solitarily on laptops trying to be creative.”

Airhead’s new album Lightness is out now via Hemlock Recordings.