Fake photography is nothing new. In the 1910s, British author Arthur Conan Doyle was famously deceived by two school-aged sisters who had produced photographs of elegant fairies cavorting in their garden.

Today it is hard to believe these photos could have fooled anybody, but it was not until the 1980s an expert named Geoffrey Crawley had the nerve to directly apply his knowledge of film photography and deduce the obvious.

The photographs were fake, as later admitted by one of the sisters themselves.

Hunting for artefacts and common sense

Digital photography has opened up a wealth of techniques for fakers and detectives alike.

Forensic examination of suspect images nowadays involves hunting for qualities inherent to digital photography, such as examining metadata embedded in the photos, using software such as Adobe Photoshop to correct distortions in images, and searching for telltale signs of manipulation, such as regions being duplicated to obscure original features.

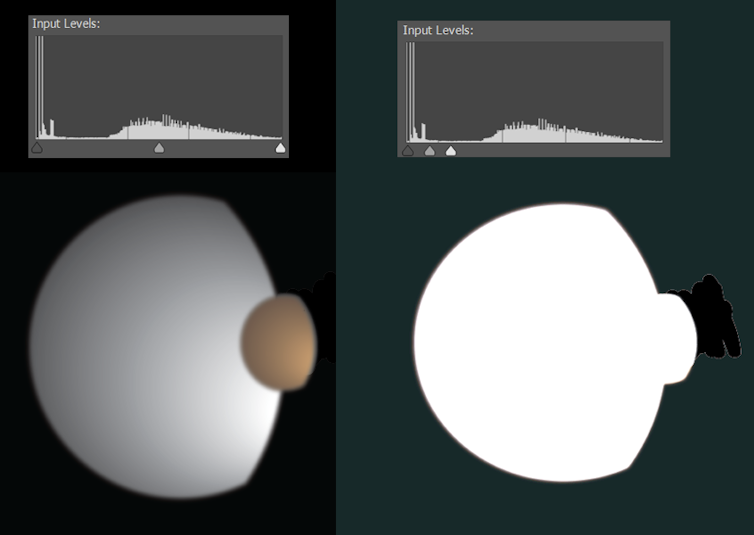

Sometimes digital edits are too subtle to detect, but leap into view when we adjust the way light and dark pixels are distributed. For example, in 2010 NASA released a photo of Saturn’s moons Dione and Titan. It was in no way fake, but had been cleaned up to remove stray artefacts – which got the attention of conspiracy theorists.

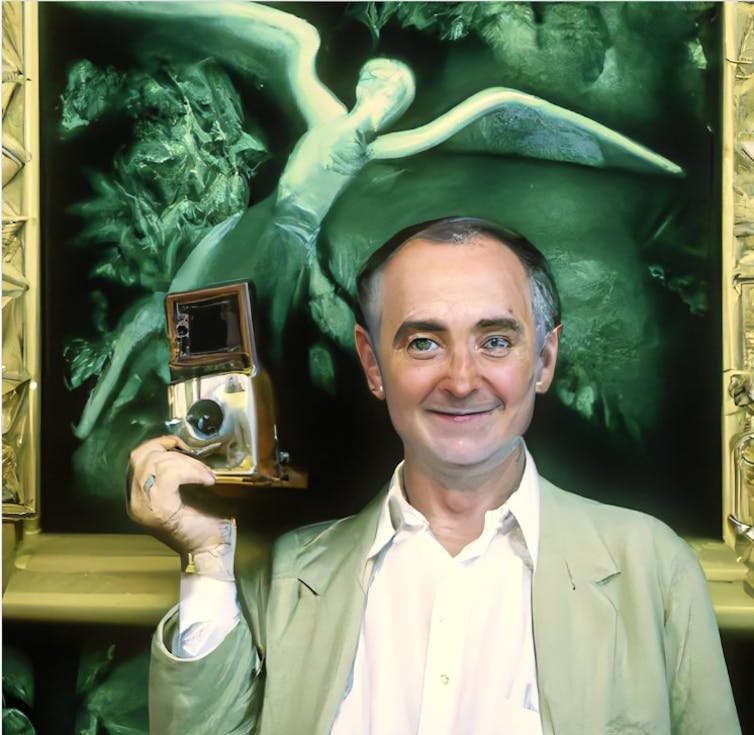

Curious, I put the image into Photoshop. The illustration below recreates roughly how this looked.

Most digital photographs are in compressed formats such as JPEG, slimmed down by removing much of the information captured by the camera. Standardised algorithms ensure the information removed has minimal visible impact – but it does leave traces.

The compression of any region of an image will depend on what is going on in the image and current camera settings; when a fake image combines multiple sources, it is often possible to detect this by careful analysis of the compression artefacts.

Some forensic methodology has little to do with the format of an image, but is essentially visual detective work. Is everyone in the photograph lit in the same way? Are shadows and reflections making sense? Are ears and hands showing light and shadow in the right places? What is reflected in people’s eyes? Would all the lines and angles of the room add up if we modelled the scene in 3D?

Arthur Conan Doyle may have been fooled by fairy photos, but I think his creation Sherlock Holmes would be right at home in the world of forensic photo analysis.

A new era of artificial intelligence

The current explosion of images created by text-to-image artificial intelligence (AI) tools is in many ways more radical than the shift from film to digital photography.

We can now conjure any image we want, just by typing. These images are not frankenphotos made by cobbling together pre-existing clumps of pixels. They are entirely new images with the content, quality and style specified.

Read more: AI art is everywhere right now. Even experts don't know what it will mean

Until recently the complex neural networks used to generate these images have had limited availability to the public. This changed on August 23 2022, with the release to the public of the open-source Stable Diffusion. Now anyone with a gaming-level Nvidia graphics card in their computer can create AI image content without any research lab or business gatekeeping their activities.

This has prompted many to ask, “can we ever believe what we see online again?”. That depends.

Text-to-image AI gets its smarts from training – the analysis of a large number of image/caption pairs. The strengths and weaknesses of each system are in part derived from just what images it has been trained on. Here is an example: this is how Stable Diffusion sees George Clooney doing his ironing.

This is far from realistic. All Stable Diffusion has to go on is the information it has learned, and while it is clear it has seen George Clooney and can link that string of letters to the actor’s features, it is not a Clooney expert.

However, it would have seen and digested many more photos of middle-aged men in general, so let’s see what happens when we ask for a generic middle-aged man in the same scenario.

This is a clear improvement, but still not quite realistic. As has always been the case, the tricky geometry of hands and ears are good places to look for signs of fakery – although in this medium we are looking at the spatial geometry rather than the tells of impossible lighting.

There may be other clues. If we carefully reconstructed the room, would the corners be square? Would the shelves make sense? A forensic expert used to examining digital photographs could probably make a call on that.

Read more: Cyber CSI: the challenges of digital forensics

We can no longer believe our eyes

If we extend a text-to-image system’s knowledge, it can do even better. You can add your own described photographs to supplement existing training. This process is known as textual inversion.

Recently, Google has released Dream Booth, an alternative, more sophisticated method for injecting specific people, objects or even art styles into text-to-image AI systems.

This process requires heavy-duty hardware, but the results are staggering. Some great work has begun to be shared on Reddit. Look at the photos in the post below that show images put into DreamBooth and realistic fake images from Stable Diffusion.

We can no longer believe our eyes, but we may still be able to trust those of forensics experts, at least for now. It is entirely possible that future systems could be deliberately trained to fool them too.

We are rapidly moving into an era where perfect photographic and even video will be common. Time will tell how significant this will be, but in the meantime it is worth remembering the lesson of the Cottingley Fairy photos – sometimes people just want to believe, even in obvious fakes.

Read more: From epic storm pics to fairies in the garden, be careful with images

Brendan Paul Murphy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.