More than 27,000 asteroids in our solar system had been overlooked in existing telescope images — but thanks to a new AI-powered algorithm, we now have a catalog of them. The scientists behind the discovery say the tool makes it easier to find and track millions of asteroids, including potentially dangerous ones that might strike Earth someday. It is for those threatening space rocks that the world would need years of advance warning before trying to deflect them away from our planet.

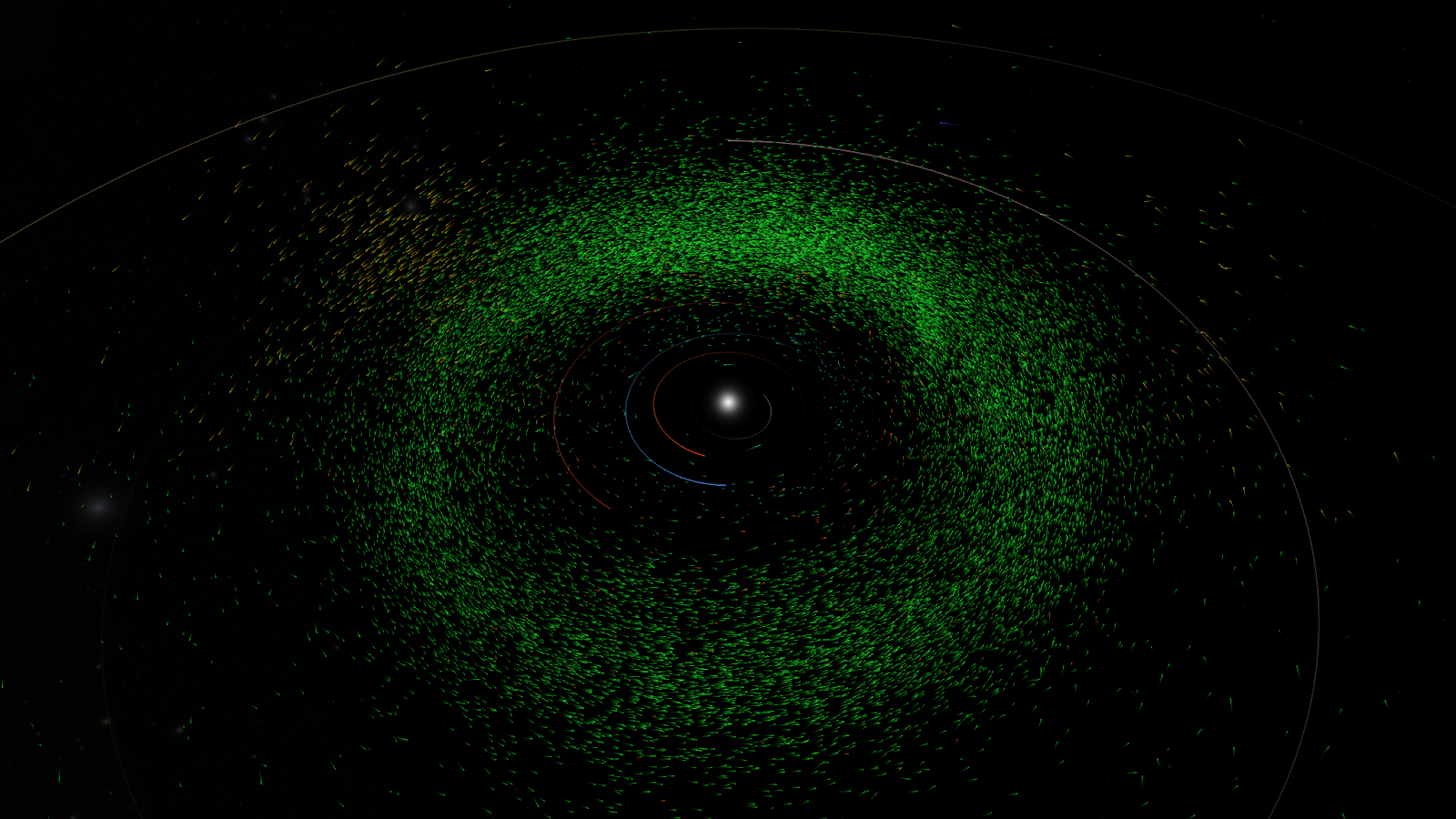

Most of the newfound asteroids hover in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, where scientists have already cataloged over 1.3 million such rocky shards over the past 200 years. The latest bounty, discovered in about five weeks, also includes about 150 space rocks whose paths glide them within Earth's orbit; to be clear, however, none of these "near-Earth asteroids" seem to be on a collision path with our planet. Others are Trojans that follow Jupiter in its orbit around the sun. Observations of these asteroids are yet to be submitted to and accepted by International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, the official body responsible for asteroid discoveries.

Astronomers conventionally find new asteroids by studying pockets of our sky over and over again, through telescope images gathered multiple times each night — usually every few hours. While planets, stars and galaxies in the background remain unchanged from one image to the next, asteroids are spotted as specks of light that move noticeably, which are then flagged and verified. From there, orbits of these asteroids are determined and monitored.

Related: How A.I. Could Help Find Alien Planets and Asteroids

"This is really a job for AI," Ed Lu, executive director of the Asteroid Institute and co-founder of the B612 Foundation, said early last month during a discussion on the discovery. In fact, AI tools designed for asteroid searches are already approaching levels attainable by humans, Lu said: "I think we're gonna quickly surpass that over the next few weeks."

The algorithm Lu's team developed, known as Tracklet-less Heliocentric Orbit Recovery, or THOR, analyzed over 400,000 archival images of the sky maintained by the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, or NOIRLab. As long as there are about five observations in 30 days associated with the same pocket of the sky, the algorithm can get to work. It's trained on a large dataset that makes it capable of analyzing as many as 1.7 billion light dots in just a single telescope image. It is designed to scope out and connect a point of light from one image of the sky to another one in a different image, and determine whether both specks represent the same object — more often than not, that indicates an asteroid moving through space, according to a description of the algorithm by the B612 Foundation.

"We don't own a telescope, we don't operate a telescope," Lu said during the discussion. "We're doing this from a data science perspective."

The scientists scaled their algorithm using Google Cloud, whose computational heft and data storage services made it easier for the scientists to test out thousands of orbits of asteroid candidates, according to a statement released Tuesday (April 30) by the B612 Foundation.

"Not only can we find asteroids in datasets that were never meant for it, but we can make every other telescope in the world better at finding asteroids," Lu said during the talk. "It's a change in how astronomy is done."

In 2022, the same team of scientists used THOR to discover 100 asteroids that had been undetected in existing telescope images. Other teams of astronomers have also leveraged AI to find new asteroids. Just two weeks ago, for instance, citizen scientists spearheaded training of an algorithm that led to the discovery of 1,000 new asteroids in archival images clicked by the Hubble Space Telescope. Last July, a software named HelioLinc3D designed to hunt for near-Earth asteroids found a 600-foot-wide (180-meter-wide) space rock expected to approach within 140,000 miles (225,000 kilometers) of Earth. That's closer than the average distance between our planet and the moon.

Scientists have so far spotted over 2,000 such "potentially hazardous asteroids" and estimate about 2,000 more are yet to be discovered. Detecting these space rocks in an effort to aid planetary defense is one of the tasks of the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, for which the asteroid-hunting HelioLinc3D software was developed.

The 8.4-meter telescope, which is scheduled to start operations next year, will take images of the southern sky every night for at least a decade, each image covering 40-full-moons of area. Scientists say this cadence, supported by AI-based software like THOR and HelioLinc3D, could help the observatory find as many as 2.4 million asteroids — double than those now cataloged — in its first six months of operations.