Bruce Dickinson may well be music's most prominent polymath. Indeed, in 2009, Intelligent Life magazine declared the Iron Maiden frontman one of the greatest living examples, alongside such highfalutin names as Carl Djerassi (chemist, author, inventor of the birth control pill), Noam Chomsky (linguist, philosopher, scientist, political activist) and Umberto Eco (medievalist, semiotician, philosopher, literary critic, novelist).

Famously, the strings to Dickinson's bow are many. Once ranked the seventh-best fencer in the UK, he's also a pilot, a brewer, a broadcaster, an author, a composer and the owner of an aircraft repair business, all in addition to his day job fronting the Irons. And in 2016, he announced plans to pilot an airship around the globe. Twice. Without stopping.

"It seizes my imagination," he told the BBC, before going on to say something no other musician has ever said. "I want to get in this thing and fly it pole to pole. We'll fly over the Amazon at 20ft, over some of the world's greatest cities and stream the whole thing on the internet."

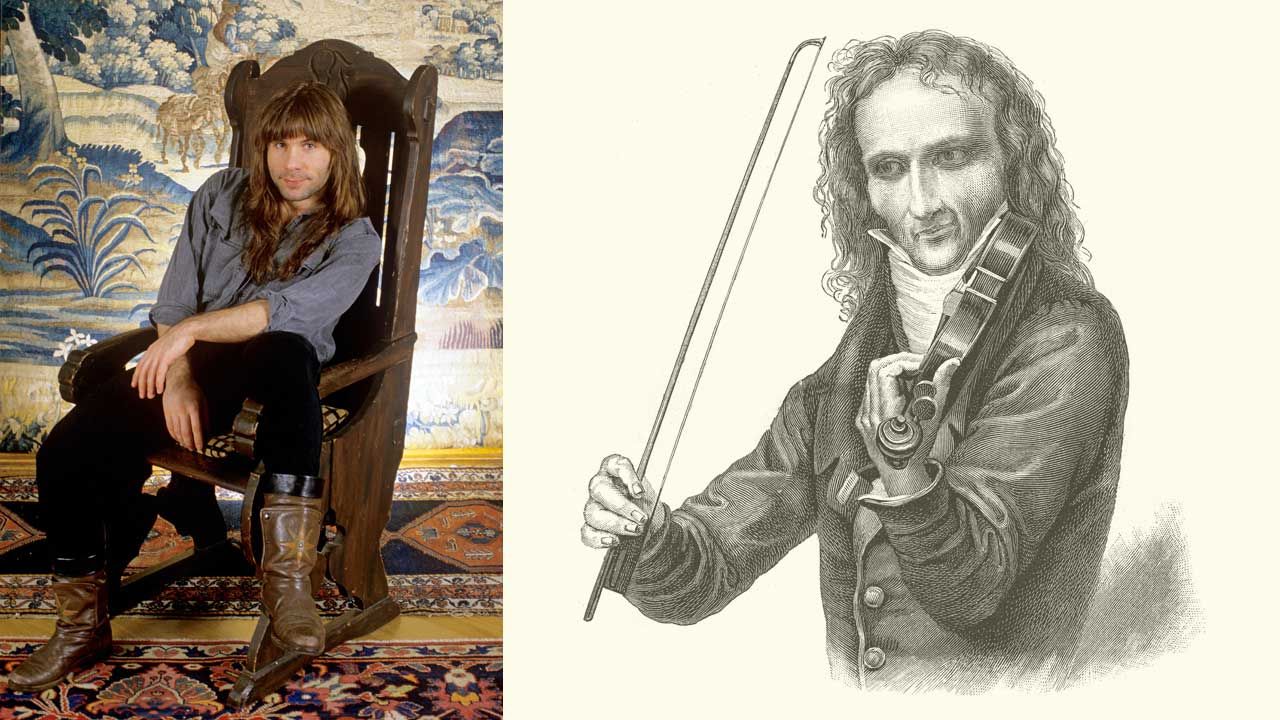

Sadly, Dickinson's helium-powered adventure has yet to take flight, and it's not the only incomplete entry on the singer's otherwise bulging curriculum vitae. For years, the Maiden man worked on a rock opera about Niccolò Paganini (1782 – 1840), the pioneering but controversial Italian violinist whose explosive playing was matched only by his chaotic, philandering lifestyle.

"Paganini was an ugly bastard," Dickinson told Metal Hammer in 1988. "Bony, beaky-nosed, hunched-back, weird-looking guy going bald. He hated his father all his life, who pushed him into music. Adored his mother. Had illegitimate children, had affairs with royalty, was reviled by the church but loved by the people. In the middle of a concerto, he would start making bird noises just like rock guitarists mess around now. After he died, his body was dug up and moved seven times because people thought his fingers were possessed by the Devil."

Dickinson wrote and copyrighted a synopsis and some song titles for the rock opera, which he described as a cross between The Who's Tommy and Amadeus, Peter Shaffer's play-turned-film about Mozart. He also developed some scene ideas, but was unwilling to commit further until funding was secured.

"One of the biggie American companies are interested," he said. "But they get things under consideration all the time."

It's unclear if work on Dickinson's rock opera has progressed since the late 1980s, but it's undeniable that Paganini's story remains ripe for such a retelling, and that the human air raid siren is the man for the job.

"Apparently, he had enormously large hands like Jimi Hendrix, which is why he could do so much on the violin, and he was a keen guitarist as well," enthused Dickinson. "He used his own unique system of fingering and improvised all the time. He broke strings during a performance once and improvised a violin concerto for one string. On stage, he dressed all in black, a bit like Ritchie Blackmore. He was an explosive Italian and would never play one note when fifty million would do!"

Paganini died in financial ruin in 1840, but his story wasn't quite finished, as the Catholic Church initially refused to bury his body due to those pesky dalliances with Satan. And while Dickinson's rock opera is yet to come to fruition, it's possible some of his ideas inspired the 2024 solo album The Mandrake Project, which explored themes related to scientific and occult genius, power, and the struggle for immortality – all concepts closely related to the myths surrounding Paganini’s supposed deal with the Devil.