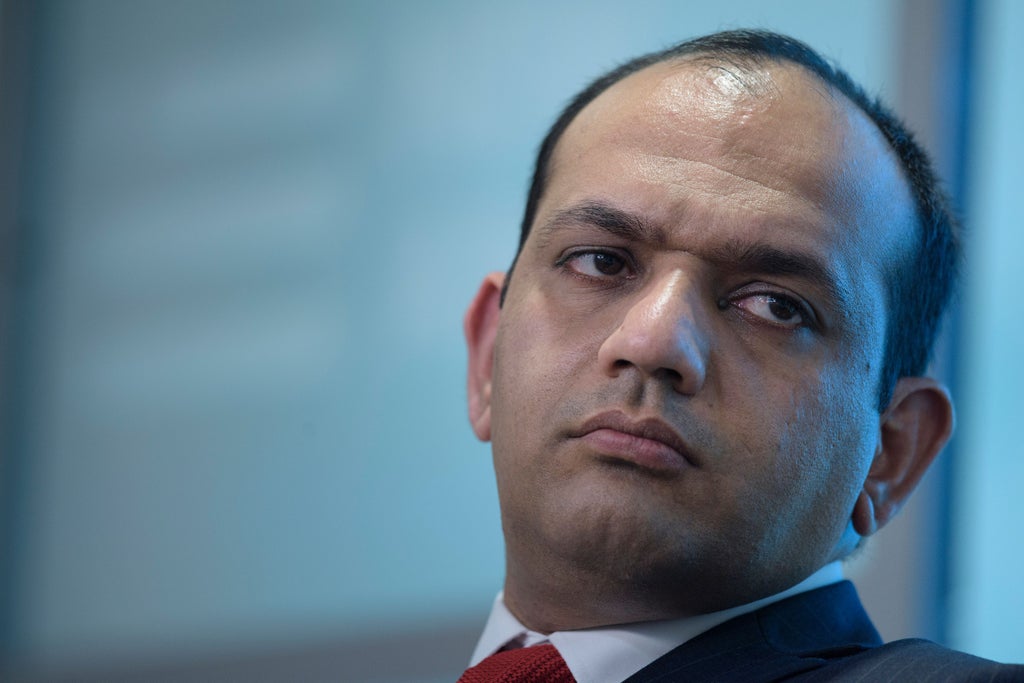

Khalid Payenda, the former finance minister of Afghanistan, who once oversaw a $6bn budget, is now an Uber driver in Washington, DC, the latest sign of the deep dislocation that followed the overthrow of the US-backed Afghan government last fall by the Taliban.

Mr Payenda fled the country a week before the insurgent group seized Kabul, telling the Washington Post that he left because he had a falling out with Afghan president Ashraf Ghani, who would himself flee the country as Taliban troops closed in.

Now, the former official, who was partly educated at US universities, teaches a class at Georgetown University for $2,000 a semester, and Ubers to make ends meet.

He told the Post he blames Afghan leaders themselves, as well the Biden and Trump administrations, for creating the dramatic collapse and ongoing difficulties inside Afghanistan.

“Now that it’s over, we had 20 years and the whole world’s support to build a system that would work for the people. We miserably failed. All we built was a house of cards that came down crashing this fast. A house of cards built on the foundation of corruption. Some of us in the government chose to steal even when we had a slim, last chance. We betrayed our people,” Mr Payenda wrote on social media shortly after the fall of Kabul.

The Trump administration’s negotiations for a peace settlement with the Taliban, which excluded the Afghan government, were the next crushing blow, according to the former finance minister.

“Maybe there were good intentions initially, but the United States probably didn’t mean this,” he told the Post, adding the Biden administration’s decision to continue freezing billions of Afghan central bank assets has made things even worse, sending the country’s economy and its unit of currency, the afghani, into a catastrophic plunge.

“It’s outrageous,” Mr Payenda said. “This is the single biggest blow you can deliver to the Afghan economy. The afghani would be a worthless, dirty old piece of paper if you don’t have the assets to back it up.”

Afghan leaders have faced intense criticism for fleeing the country, most sharply directed at former president Ashraf Ghani, who took refuge in the United Arab Emirates.

“He will be known as the Benedict Arnold of Afghanistan. People will be spitting on his grave for another 100 years,” Saad Mohseni, who owns one of Afghanistan’s most popular television stations, Tolo TV, told Al Jazeera at the time.

Critics argue that negotiations were underway with the Taliban to ensure a smooth takeover of the machinery of Afghanistan’s government, but the news of Mr Ghani’s exodus tanked the discussions.

The former president has defended his conduct, arguing that if he stayed he would’ve been killed, which would have set off street violence. Mr Ghani has also called allegations he fled the country with $169m in cash “baseless.”

"I left at the urging of the palace security, who advised me that to stay risked setting off the same street-to-street fighting the city had suffered during the civil war of the 1990s," he wrote online after leaving the country, which he said he did to "save Kabul and her six million citizens".

Mr Payenda, the finance minister, was able to move his family to the US via the Special Immigrant Visa programme, which allows personnel who worked with the American government in Iraq and Afghanistan to come to America.

As of February, however, around 60,000 Afghans who had worked with US forces remained stuck in Afghanistan, thanks to long delays in visa processing.

“Thousands are still waiting — terrified of Taliban retribution, hiding in basements,” Ryan Crocker, former US ambassador to Iraq and Afghanistan, wrote in the New York Times in February. “It’s time to bring them to America.”

Critics also point that many who risked their lives to help US forces in countries like Yemen and Syria don’t have similar immigration programmes available to them.

Though international aid efforts helped avert a potential famine, those inside Afghanistan are also facing economic problems so deep they’re “approaching a point of irreversibility,” the United Nations envoy to Kabul, said in early March.

The Taliban has still not been recognised as the legitimate leader of Afghanistan by much of the international community, and many Taliban leaders are under heavy sanctions from the US and UN.

"We do not believe that we can truly assist the Afghan people without working with the de facto authorities," UN Special Representative Deborah Lyons told the UN Security Council, asking for a new mandate for her mission.

International aid, which once made up more than 70 per cent of Afghanistan’s government spending, has dried up, and about $9bn in Afghan assets remain frozen in banks around the world.