Cape Town, South Africa – In September 2012, when Akinwumi Adesina was Nigeria’s agriculture minister, the country witnessed one of the worst-ever floods.

The deluge engulfed 30 of Nigeria’s 36 states, killing 363 people and displacing more than two million others. The floods washed away farmlands, settlements and critical public infrastructure such as roads, bridges and power installations.

“Everybody panicked that there was going to be a food crisis. I must have been the only person in the country who said we can avoid a food crisis,” Adesina, 62, told Al Jazeera.

The minister implemented a plan to accelerate the growth of maize, wheat and rice in the dry season as the country faced devastating food shortages. Growing those crops at that time of year was not typical in Nigeria, but it increased the food supply. The government also distributed free seeds and fertilisers to farmers affected by the floods and subsidised inputs for unaffected farmers, to boost food production.

“By the time we finished the action plan, instead of the price of food going up, the price of food crashed in Nigeria, by March. We started planting in October. By March, we had brought down the price of food.”

It was possible, Adesina said, through “knowing science, knowing technology, and deploying the right instruments at the right time”.

Effect of Ukraine war on Africa

Now, in his current role as the president of the African Development Bank, the continent’s largest multilateral lender, Adesina is trying to avert a food crisis on a larger scale. As the war between Russia and Ukraine draws into its second month, natural gas, wheat and fertiliser prices have skyrocketed.

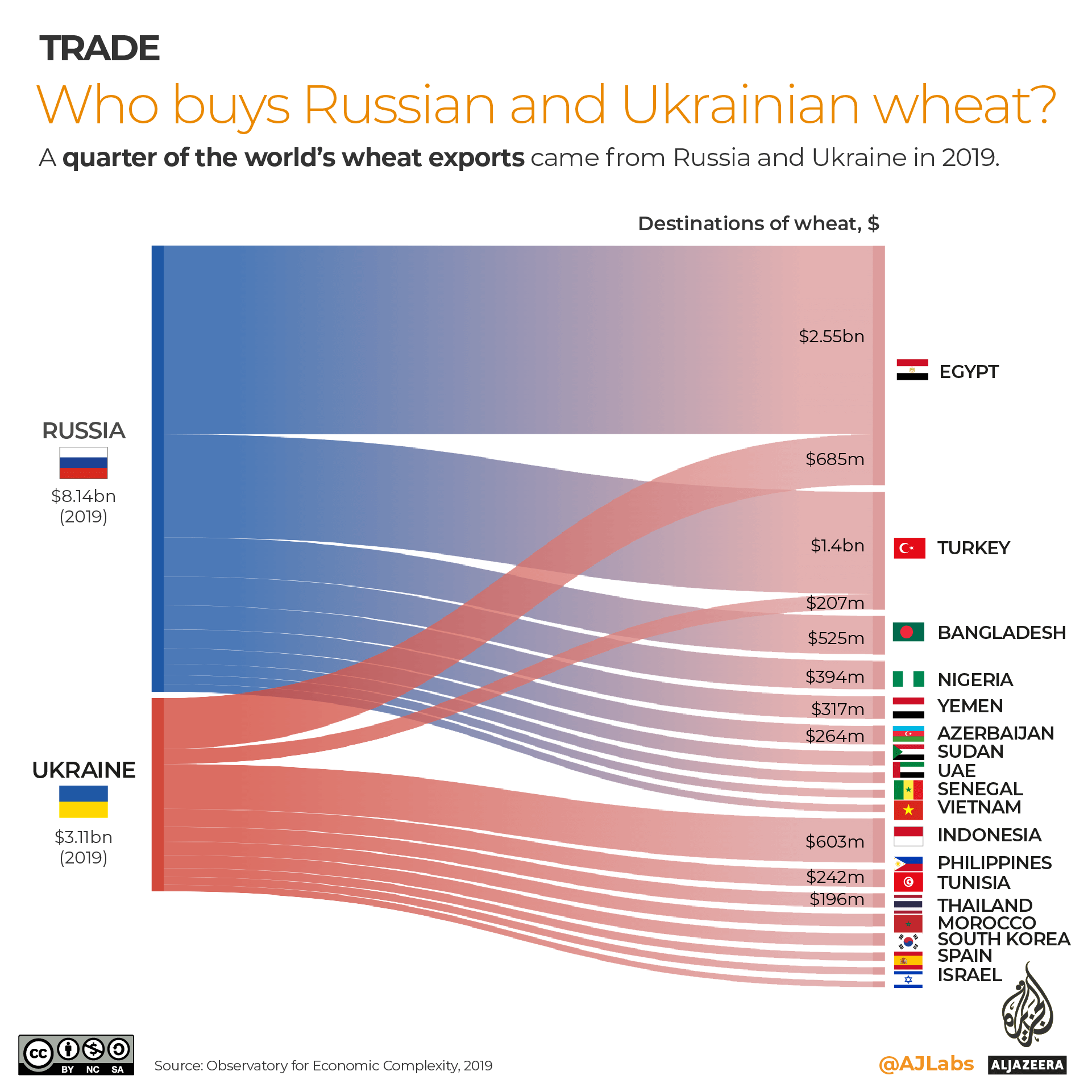

Together Russia and Ukraine produce more than a quarter of global wheat exports, and Africa is heavily dependent on both countries. Wheat imports make up 90 percent of Africa’s $4bn trade with Russia and almost half of the continent’s $4.5bn trade with Ukraine, according to AfDB.

“One-third of the cereal supply of East Africa comes from those two countries, and Egypt is badly affected. So is Algeria and Morocco, Somalia and several other countries. So, if we don’t manage this very quickly, it will actually destabilise the continent,” Adesina said.

He said the war would affect Africa’s economy in a few major ways. Already, it has roiled financial markets, causing sky-high interest rates. “You begin to see what has happened also in terms of the yields for euro bonds that are posted by African countries. The spreads are very, very high as a result of this,” he said.

But perhaps just as important, commodity prices are on the increase, including that of wheat which has “gone up by 64 percent globally”, the same price around the 2008 global food crisis, he said.

Fertilisers, a key component of the agribusiness sector, have also been affected, and the bank chief knows that that could spell disaster.

“The price of urea has gone up by 300 percent. All of that is saying, that it’s [the war] driving inflation in Africa, and it could — if not quickly well-managed — trigger a food crisis in Africa,” Adesina said.

Africa’s emergency food plan

Adesina is working on a $1bn emergency food production plan for Africa to avoid food shortages and bring down inflation. The AfDB-led project will help support 20 million farmers with access to climate-resilient agricultural technologies to boost food production to feed 200 million Africans.

Under the plan, farmers will be able to produce 30 million metric tonnes of food, including wheat, rice, maize, and soya beans. The output is expected to be valued at $12bn.

The COVID-19 pandemic plunged 26 million Africans into extreme poverty. “Now with this looming food crisis, and with the accelerating inflation, we’re going to see a lot more – a couple of million more – people fall into extreme poverty. And why? Because in the poor household, the price of food accounts for roughly 65 percent of their household expenditure.”

But Adesina is optimistic that this could be avoided if the emergency plan receives enough international support.

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva was “very supportive” of the plan, he said. Adesina plans to call a meeting of African ministers of finance and the ministers of agriculture “very soon” to discuss it.

Adesina plans to deploy $1bn in two batches a year, in time for Africa’s growing seasons – May through to July in the northern hemisphere and October to December in the southern hemisphere. As it is an emergency facility, the funds will be grants, not loans.

“We’re going to be doing all we can for the rest of March and April to be able to get it,” he said. “Whatever we get, we will deploy immediately to begin to get seeds in the ground and for us to grow more food.”

African fuel for Europe

Some observers believe the conflict in Eastern Europe has presented an opportunity for African countries to become key energy suppliers and Adesina agrees.

“With the war in Ukraine, what that has actually shown is that Europe needs to diversify its own energy supply out of Russia,” Adesina said. “It depends on Russia for 45 percent of all of its gas, almost 115 billion cubic metres of gas — a place to look to is Africa.”

AfDB worked on a $25bn deal with Mozambique in 2020 for liquified natural gas (LNG), which will make the country the third-largest exporter of the commodity in the world. There are also hopes that the trans-Saharan pipeline — currently under construction — which will span from Nigeria to Algeria will be an integral part of any new agreements.

Adesina agreed.

“There are new gasfields that have been found in Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, so Africa can become a strategic supplier of gas for Europe. And I believe that Europe should invest together with us in the critical gas pipeline infrastructure to get gas from Africa to Europe,” he said.