The first time I heard The Smashing Pumpkins’ Adore was in my school’s sixth form common room. My friend Ben had bought it the day before – on release day – and brought it in at lunchtime to play on the portable CD player that was in the corner. I remember sitting listening to it and, from the moment the hushed, melancholy tones of To Sheila started the record off, I loved it. Ben, on the other hand, absolutely hated it. He wanted more of the same rough if beautiful, raucous if orchestrated, grunge-tinged alt.rock that had, until that very day, defined the band’s sound.

Perhaps my more enthusiastic reaction was because I didn’t have any expectations. My little knowledge of the Pumpkins extended to a few songs (Disarm, Today and one or two I can’t remember) a girl I knew had put on the other side of a bootleg cassette version of The Offspring’s Smash. They were good – great, in fact – and I would fall in love with the band in a big way maybe a year or so later and become bootleg obsessed with them, but since at the time I was more into Bruce Springsteen, Jawbreaker, Eels, Modest Mouse and a whole load of other stuff they didn’t mean everything to me. That’s probably why I took to Adore so well. I didn’t view it as a continuation of their legacy, but as an album in and of its own right, the first one I’d heard in its entirety and one which was shaped by situations I only came to understand later.

To me, Adore is one of the best – maybe even the best – albums in the Pumpkins’ catalogue. That’s not to diminish either Siamese Dream or Mellon Collie & The Infinite Sadness. Both are incredible pieces of work, of art, of music – the latter one of the true times you can accurately describe an album as a true tour de force – but listening back to Adore now I find it hard not to place it up there with both of them. As a good friend of mine always says: it’s not wrong, it’s just different. And just because it’s different doesn’t mean it’s not worthy.

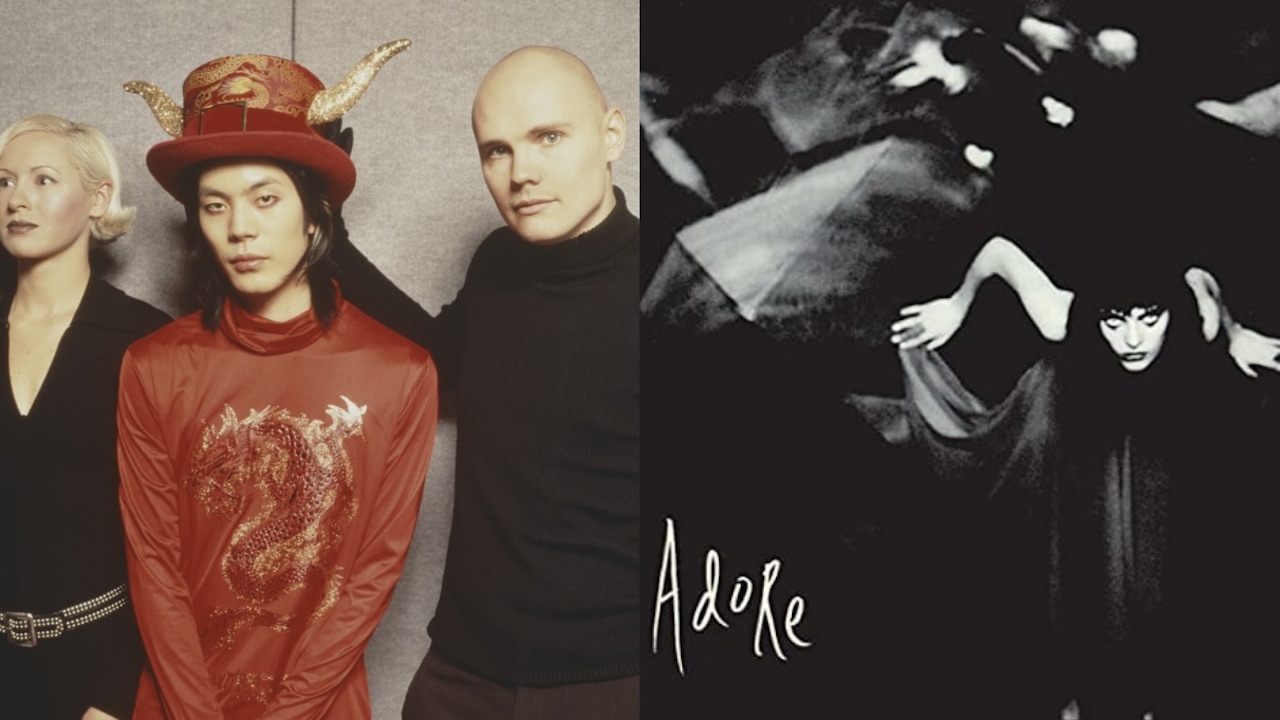

Perhaps more than any of their other records, it was an album born out of its own circumstances, specifically the heroin overdose that left touring keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin dead and got Jimmy Chamberlin kicked out of the band, as well as the inter-band struggles that arose as a result of the pressure of fame and their inability to cope with it. Yes, they deliberately set out to do something totally different from what they’d done before, but you can bet it was as much out of necessity as desire.

But listen to the sublime and gentle lilt of To Sheila, the electronified sleaze and menace, respectively, of Ava Adore and Pug, the forlorn resignation of For Martha, the sheer magnificence and melancholy of Shame and the abject, piano-led heartbreak of Blank Page. Those last two songs alone are some of the greatest in The Smashing Pumpkins catalogue, but they’re also part of a much greater whole. It might have been divisive at the time - and sold badly, to Billy Corgan's disappointment - but, oddly, there’s no doubt that Adore is the band’s most cohesive album.

Talking to Rolling Stone in December 1998, six months after the album's release, Billy Corgan was asked what he might do differently if he had to record the album all over again.

"I would have gone further with the vision of the record," he replied. "I would have made it more opaque, more dense, more hard to reach. At some point along the way, I tried to pull it in a little bit."

He continued: "The most amazing compliment I get on this album is, people pull me aside and go, 'I have been listening to this record over and over again. I can’t get it out of my stereo. When l first listened to it, I thought it was kind of OK. But it snuck up on me and hit me like a ton of bricks.' Maybe it’s like a Lou Reed Berlin kind of record, where it’s got to sit for a while, be digested and maybe get away from the politic of a certain time."

Personally, I fell in love with this album first time around. But now it’s happening all over again, and it feels just like the first time.