Hoa Xuande has been waiting to get some good lines. And the Australian actor delivers plenty as the star of "The Sympathizer," HBO's seven-part adaptation of Viet Thanh Nguyen's post-Vietnam War novel, a feast and feat of wordsmithery that earned him a Pulitzer.

"A line that comes to mind is: 'Wars never really die, they just hold their breath,'" Xuande tells me. "It encapsulates our inability as humans to forgive each other or move on sometimes. That we can all to a certain extent carry a war within ourselves, waiting for a chance to ignite again, which is the unfortunate nature of why we as humans still choose to fight each other over anything."

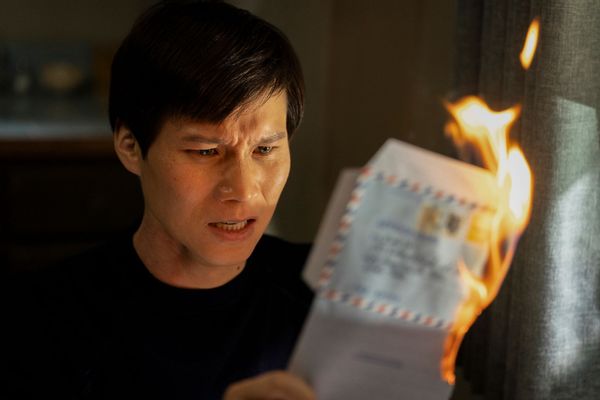

It all comes down to language in "The Sympathizer," in which Xuande plays Captain, a bilingual double agent whose ability to speak fluent Vietnamese and English makes him an invaluable asset (or is it a pawn?) for everyone he encounters. Captain is secretly a North Vietnamese communist mole planted in the South Vietnamese army, while also reporting to the CIA when Saigon falls in 1975, sending him and his Southern associates fleeing to the United States.

Herein lies the value of "The Sympathizer" as an American-made tale – co-created by Park Chan-wook and Don McKellar – that offers the rare Vietnamese perspective of the war and its aftermath, especially for the refugees displaced and mourning their family, their home, their identity, their peace. Xuande is the offspring of Vietnamese refugees like I am, although we've ended up on opposite sides of the globe. Not having experienced the war ourselves, we're dependent on what has filtered down to us through our parents: scant, often disjointed details devoid of context and a true accounting of the loss involved. Language is often a barrier as well for offering the types of complex, nuanced reflections that are challenging for elders learning their second or even third language upon immigration.

"I'd heard stories from my mom and dad growing up," Xuande confirms. "And it feels really bad to say, but there are the times when they told me stories, but I wasn't really paying attention. As I've gotten older, when they've retold me these stories, especially when they're more pertinent to things like this show that I actually started to listen and actually understand what it was they really had to go through."

The war in Vietnam is complicated. Hell, even the decision to call it the Vietnam War versus the American War, which is what Vietnamese people call it, comes with its own baggage and misinterpretations. Gruesome narratives from the U.S. like "Apocalypse Now" and "Platoon" do little to foster understanding of the people whose country was invaded by those purportedly sent to save them.

"What the show allowed me to do was to really deep dive, find out the causes of the people, a lot of which I've never really fully investigated before," Xuande says. "When we watch movies about the Vietnam War, we get the perspective, mostly of the Americans or the allies. And so doing a project like this really allowed me to deep dive into the perspective of the Vietnamese civilians on the ground because there's a lot of those stories that aren't told. If you really look deep enough you can find them, and also the horrible campaigns that were run actually on all sides and how that really impacts the war."

Fluency is Captain's cultural currency as an interpreter, an intermediary and a spy. But there's one extra layer to Captain's linguistic deployment that is worth considering. In the series, as in the novel, we realize that we are getting an accounting of Captain's experiences as a written confession. The entire tale is told in retrospect now that he's returned to Vietnam after his sojourn in the U.S. and it's his North Vietnamese comrades in the reeducation camp — or are they his jailors? — whom he must convince of his loyalties.

He must convince us as an audience as well. Because how much can we trust a man who is telling his tale under duress, while locked in a cell and denied nourishment and human interaction? How much can one know the motivations of a man whose name we never learn? Like the protagonist in Daphne du Maurier's "Rebecca," Captain tells his story in first person, but never names himself. Instead, he relates a tale that occasionally incorporates storytelling flourishes like flashbacks, elaborate tangents or imagined conversations by others in his absence. It has all the colorful characters, wry observations and unbelievable pacing that can be found in a novel. The piled sheaf of papers from his confession resembles a manuscript.

Fight for your right (accent)

"Go be the adviser for our people," Man responds. "Your influence may be small, but as they say, if you keep rustling the winds will gather and give us a storm. Give us some good lines."

Again, Captain must leverage his language skills, this time to afford his people some smidgen of a presence in Hollywood. It turns out that director Nicos Damianos, (Robert Downey Jr.) who's making his Vietnam War magnum opus "The Hamlet" only wants a yes man, not actual input. Therefore, Captain must go to battle for every line, especially since Nicos never wrote any for his Northern Vietnamese background characters, whom he compares to the docile water buffalo.

"Robert [Downey Jr.] as the auteur is probably the most antagonistic person that I face in the show," acknowledges Xuande. "He's really just a major a**hole. For my character's sake, I felt like that was really what it must have been like to really have to fight for your representation back in the '70s when they were illustrating apparently your war back to you in a certain way that only highlights their humanities.

"That antagonistic character representing the establishment that is Hollywood makes you really feel like you are nothing," he continues. "There are a lot of those eye-roll moments on set [back then]. I feel like that's the only way you can really deal with that at the time because they're not going to listen to you. You've been told by an establishment that you're just a few people who apparently were so lucky to have survived and made it to the mainland of America. Then, apparently, you just have to eat up whatever they feed you."

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C61S0skO204/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

The need for accurate representation in Hollywood is often misunderstood as merely a gift affecting the marginalized – to afford them jobs they may not be considered for and to see themselves onscreen. Certainly, both are necessary and empowering, but equally as important, it's about how those in power — in this case, a white genius director and his presumably predominantly white audience — will begin to see the Vietnamese as people and not some intrinsically alien, subhuman other.

Therefore, by making Damianos concede that his movie's villagers need spoken dialogue, Captain has forced the director to acknowledge the Vietnamese people's very humanity. This might have been enough for the American filmmaker, but Captain isn't content with just a show of representation. Captain first points out that one vocal Asian extra is not even speaking Vietnamese . . . because she's Chinese. Thus, Captain gets the green light to recast his own people as background extras, which leads to the following conversation with his Southern General, who will source extras from the refugees in his camp.

"What accents are required: Northern or Southern?"

"Northern is better but if they're from the South I can coach them."

It's a conversation that only matters to the Vietnamese people involved, since Damianos certainly doesn't know or care. (His Assistant Director thought Vietnamese was just another type of Chinese accent.) Here, the accent or more accurately the dialect that's being discussed indicates far more than just which geographical region one hails from. It's an indicator of one's possible allegiance, a shared mindset and experience that means so much more outside of one's homeland.

Damianos' fictional film "The Hamlet" is set in North Vietnam, hence the need for those with that dialect. Captain's loyalties may be red, aligned with the North, but he was born in the South, similar to the actual spy on which he's based.

"It's Pham Xuan An. He was the real-life spy that inspired 'The Sympathizer,'" says Xuande. "He actually has a southern accent, and so it actually confirmed to me that I didn't need to have a Northern accent for this character to be plausible. I could actually just use my natural Southern accent. And my Southern accent is not the modern-day accent. It's probably closer to 1970 because of the way my parents spoke when they left Vietnam, and that is the only real reference that I have of that time through my parents. And so my accent naturally comes from them."

While Xuande could speak conversational Vietnamese, he needed to perfect it for the series. His Vietnamese skills needed to project who he presented himself to be as highly educated and well-trained. After all, any self-respecting spy wouldn't let anything slip through sloppy language.

"Growing up in Australia, especially when I didn't really have any Asian friends, I was kind of ashamed of being Vietnamese," he admits. "I didn't want to speak my language. It took me a long time to accept and be comfortable with the fact that I had a second language and I could speak it.

"When I took on this project, they put me through a two-week crash course," he continues. "I learned that quite quickly because I obviously have a grasp of the language. But there's words that I've never used before, which were really difficult for me to learn when you have to say things like 'Commandant' or 'public execution' or 'dialectical materialism.' There are words that you probably wouldn't even say in English, let alone Vietnamese. And I'm learning these words for the first time. So they that was a bit of a struggle."

"The American accent I'm putting on now, it's kind of diluted, not as good as it was when I was shooting," he says. "I just just do this for ease of interviews. To be honest, I can switch to my natural accent, but you'll probably be scratching your head for half the time."

Xuande is not alone in the decision to alter his speech to be better understood, especially by the American press. Having interviewed both Christian Bale and Jodie Comer – before and after they decided to soften and dilute the stronger aspects of their native speech – I admit that the latter does make for better transcribing and less confusion.

It's also a skill they can wield with precision and ease that many of us can't.

A meeting of minds

I don't use the word "wield" lightly when it comes to the ability to change speech. Language is central to the power in "The Sympathizer," referring to both the story and the man. We get one of the first inklings of Captain's true mastery of language whenever he's challenged by one of the incarnations of Robert Downey Jr. in the series.

An extreme example arises from Captain's external appearance. Being half Vietnamese and half French invites the curiosity from Prof. Hammer (also Downey, Jr.), who teaches Orientalism in grad school and therefore believes he understands Asians . . . often better than they do themselves. When Captain attends a donors' party, Prof. Hammer calls upon him to perform. It's not a song or dance, but rather a thought experiment for Captain to break down his two sides: Western and Eastern. It's condescending and othering, as Hammer points out to guests that Captain's mixed race makes a "lovely combination as you can see, but complicated."

Captain holds forth and delivers the following speech with aplomb:

Contradiction: The crux of the issue has always been about contradiction. The Occidental side of me see contradiction as something to overcome. But the Oriental side as something to endure. Hence the Oriental side of me is never afraid to accept contradiction when faced by an unexpected turn of events and say, "I expected this." But the Occidental side says, "What? Why did this happen?" and immediately begins to analyze.

The Oriental me feels comfortable in a crowd, but the Occidental me is always ready to take the stage. I think in two frames of minds either/or to the Occidental me and both/and to the Oriental Me. So accordingly, half of me values independence, but the other half appreciates interdependence. Also ––

At this point, Prof. Hammer interrupts, a bit flustered by being outmaneuvered.

"I found the speech really fun to do," says Xuande. "If you're going to analyze what that scene is, it speaks to the establishment that is trying to dissect our Asianness, that is always trying to perceive the Asian person as something other than potentially human. That there's something that is like us, and there's something that isn't us. Imagine having to write a list of all the qualities that apparently you possess, that aren't normal or human-like or whatever. All throughout history, we've done that to marginalized people, and so I think that scene encapsulates that very notion that there was a point in time when education or cultural establishments tried to basically analyze people as if they weren't people."

Prof. Hammer wants a performative type of Asianness, one that conforms to what he believes Captain to be, and he gets that . . . at first. Captain dutifully accedes to the professor's wishes by delineating a binary persona, but as the speech goes on, it's clear that he's commanding the party through his charismatic rhetoric. He's not letting himself be relegated to being a mere spectacle, which is why Hammer stops him mid-sentence.

"Robert does a really good job of hamming up that perspective of having some kind of superior understanding of what our culture is, that somehow our culture has to be educated back to us," says Xuande. "He embodies that idea of: we know what you're supposed to be like, and we know the differences and we know what the similarities are. These are the things that you're supposed to do and not supposed to do. And if you're not doing it, then you're wrong."

Being a double agent of mixed heritage also makes Captain the ultimate stand-in for the dual immigrant identity – having left the homeland and yet not wholly embraced by the new country because of one's looks. Captain is the perpetual outsider no matter where he is, but he gains a conditional entry through his facility with language. This eventually becomes his undoing, however, because to truly understand a language is to understand the people who speak it and their ways of thought. Their very ability to embed in other groups is why they might be swayed to their side.

"I think his weakness is that he can see all the sides," observes Xuande. "Therefore he doesn't quite know who is actually – it's really hard to put these words because there are no victors and there are no losers. Everyone loses, right? So when you start teetering on understanding that actually, everybody is right and wrong at the same time, it actually puts you in a position that you're you are at your most vulnerable."

Sure, language can provide Captain's primary weapons for both offense and defense. And sometimes deploying them blows up in his face.

More than a few people begin to distrust how well he speaks English and know American culture. His own blood brother and handler Man tries to make Captain admit that he's more American than Vietnamese now. But it's the various Robert Downey Jr. iterations who push Captain to reveal that he's not as docile as the water buffalo they're expecting. While he's had the most combative interactions with director Nicos Damianos, it's the friendly collaborations with his CIA mentor Claude (Downey Jr.) that are filled with ongoing tension. Every time the Captain corrects Claude's misattribution of a quote or misidentification of an American musician, it feels like a test. At what point will Claude be fed up with his mentee having his own thoughts and will?

But it's as Captain that Xuande has the most opportunities to fully embrace the braided dualities of being a mole, an immigrant, an actor – all of which require gauging one's audience and delivering an appropriate performance to get through to them. It seems fitting then, that he cites the 2016 science fiction film "Arrival" as resonating strongly with him. In the film, unlocking the secrets of how to communicate with alien visitors has the power to change how one experiences reality.

"I recently watched 'Arrival' and that's by Denis Villeneuve," says Xuande. "I still remember that movie quite often because it's just got such a beautiful message of understanding the world. It's a message about, if we knew that we could be better, would we try and act better? And if I can still remember a film years on after it's released, I feel like that's a project that's going to have a lot of impact, that's going to resonate with a lot of people.

"So I feel like this project ['The Sympathizer'] was perfect in that way. Because regardless of what depictions of the war of this, that and the other or some of the tragic moments or light-hearted moments, I think the message of this show will really resonate and carry on through more than just the Vietnamese diaspora."

The captain has spoken.

"The Sympathizer" airs Sunday nights on HBO and streams on Max.