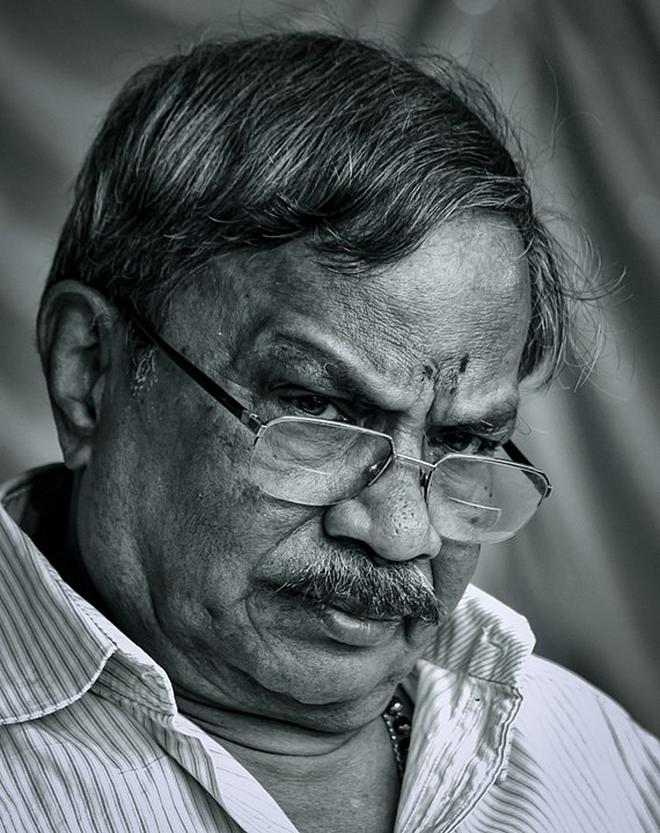

Of all the facets of Kamal Haasan — actor, director, screenwriter, dancer, singer, politician and more — perhaps the least discussed is his engagement with Tamil literature. He has often collaborated with writers for his films and has spoken of the various literary influences on his life and work. Last week, Haasan caught up with prolific Tamil writer Jeyamohan, whose new book, Stories of the True , the English translation of his bestselling short story collection, Aram , was recently released. In a freewheeling conversation at the actor’s studio in Chennai, they discussed world literature, their philosophical and aesthetic beliefs, the intersection of literature and cinema, and more. Edited and condensed for length and clarity:

Kamal Haasan: It’s been nearly 11 years since you wrote this book in Tamil, but it still rings true. I believe you wanted to write it as non-fiction initially, because it is about real people. What made you fictionalise it?

Jeyamohan: Around the time I turned 50, I felt like I had lost faith in idealism. In an attempt to regain my faith, I started writing about the idealists I had met until then. I wrote the story, ‘A Hundred Armchairs’, as an essay at first, but it did not work. For me, fiction was truer to the original spirit. An essay can only express an idea. It cannot express the spirit. So, I chose fiction.

When this collection came out, many readers wrote to me about similar personalities they knew of. I published those letters on my website. So, the entire process of regaining faith in idealism became a collective exercise.

I have to tell you that I was surprised to hear that you introduced the book on a popular TV show. I told my friends then, that Kamal too seems to be trying to regain his faith in ethics and high morality.

Kamal Haasan: That is true. That is why I did Hey Ram. It was my testimonial to my hero [Gandhi]. He is a hero for the both of us, isn’t he? He is an enduring testimonial for upright living.

Jeyamohan: Are you an idealist? This might sound a bit exaggerated, but I feel that Tamil people have been somewhat corrupted by politics. How do you keep your faith in democracy and in idealism?

Kamal Haasan: Democracy is not a safe deposit. It’s not something we locked away safely on August 15, 1947. That’s not how I see it. Constant vigil is required to keep democracy intact. Everybody has to take part in that. If you don’t affect politics, politics will affect you. But to understand that, I had to turn 50.

Jeyamohan: So you’re not impatient with the general public?

Kamal Haasan: I can’t be. Gandhiji addressed a meeting of the Congress in 1908. It took another 40 years for his dream to come true. These things take time and it can go whichever way. But that’s purpose. I’ve said earlier that you and Ilaiyaraaja work too much. I would say, relax, what’s the hurry? But I take my words back now. It’s like Salieri telling Mozart that there are too many notes. I think it might have been envy too. I realise now that it’s not a race. It’s not a winnable race, certainly. Especially after Venmurasu (2014-20), I don’t think there’s any writer who can compete with you in terms of output. That tenacity of purpose, that in itself, is an ethical stand you’ve taken.

Cinema and literature — two sides of the same coin?

Jeyamohan: A Malayalam filmmaker once said that the era of films based on literature ended with O.V. Vijayan’s Khasakkinte Itihasam, because, according to him, cinema and literature had become two very different things. Do you believe so?

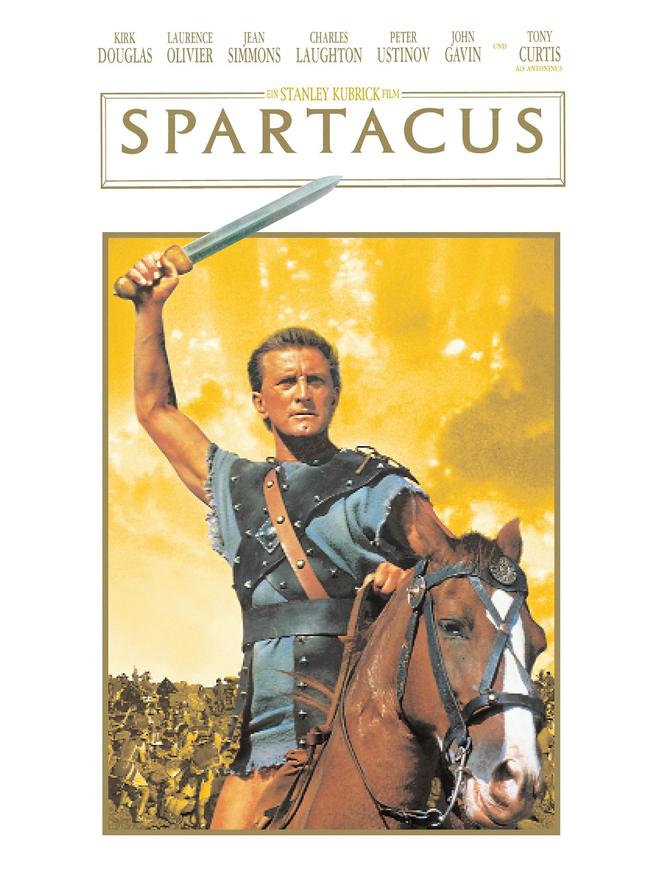

Kamal Haasan: No, I don’t believe so. I recall a meeting held 44 years ago. Bridging literature and cinema was at the core of the discussion that day. We wanted writers like Balakumaran and Sujatha to get into films. Later on, it came to be believed that the best of directors would handle all three aspects — screenplay, dialogue and direction — themselves. But to me, cinema is a democratic art in which many people have to come together. Spartacus — the 1960 film that brought together Dalton Trumbo, Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas — is so alive even today. Combinations such as that are emerging [in Tamil cinema] only now.

A space for empathy

Kamal Haasan: Coming back to ‘A Hundred Armchairs’, the depth of your anger and sorrow in that story made me question who you were.

Jeyamohan: When I first wrote the story in 1992, I kept referring to the main character as ‘him’. But the story was dead. I told myself that I could not write it and put it away. Later, when I wrote this collection, I came back to that story and rewrote the main character in first person. That’s when empathy entered the story.

Kamal Haasan: Yes, that’s what made me wonder if you were from the community [of the protagonist].

Jeyamohan: Piridhin noi thannoi pol potrakadai. Feeling the pain of another soul as if it were your own — that is fundamental to literature. If that’s not possible, literature will suffer. If I cannot feel the pain of Ukraine, then I cannot feel the pain of my neighbour too.

Also, as far as writing is concerned, from the beginning, I believed in two things. Firstly, in story. I think the art form of story is one of the greatest inventions of man. Therefore, I was clear that I wanted that in my works. Secondly, emotion. I make no compromises on that count. [After the wave of modernism], I feel these are the two aspects I brought to Tamil literature.

When I wrote this book, I realised another thing. Those I take to be my teachers… Sundara Ramaswamy, Ashokamitran… they would not eulogise another personality. They presented themselves in their writing. The ‘I’ Ramaswamy wrote about, was himself. I would say that about myself too, to some extent. But just as Kabilar sang about the king, Paari, and recorded him in history, I have set down ‘Elephant Doctor’ [and others] in writing. I feel that it is a writer’s duty to do so. An idealist lives his life a certain way. It is the responsibility of a writer to record it for posterity.

Kamal Haasan: You say Sundara Ramaswamy was your teacher. For me, even those I’d never seen were my teachers. Let’s take Saadat Hasan Manto, for instance. When I wrote the scenes featuring Saketh Ram [in Hey Ram], I felt like Manto was breathing down my neck, as if he was watching me write. Manto had such a strong influence on me. I am not so influenced by O. Henry, for example. Because what Manto talks about is my country, my story, I know the topography, it’s the land my father tread on...

Adaptations and complications

Jeyamohan: Have you ever adapted a literary text into a screenplay? What kind of complications can adaptations pose?

Kamal Haasan: I would like to share this example [of a role reversal]. The screenplay Trumbo wrote for Spartacus was a novel in itself. I was so in awe of it, I went and read Howard Fast’s novel [on which the movie is based]. It begins in reverse! And it reads like a screenplay. There were no takers for the book when Fast wrote it in the 50s. Until Kirk Douglas came forward, no one dared to make a movie on it. U.S. senator McCarthy’s tyranny was at its peak and Trumbo had fled the country. But even during those troubled times, Douglas credited Trumbo for Spartacus. That’s how difficult things can be.

Back home, Jayakanthan himself oversaw the film based on his book to make sure it was heading in the right direction… It had to be done that way in those times. In Malayalam, as you know, the writer-filmmaker relationship is well established. In fact, I would say, that in Malayalam, filmmakers are greatly influenced by writers.

Jeyamohan: That, I would especially credit to M.T. Vasudevan Nair. He laid the path for writers in [Malayalam] cinema. He was truly able to influence the success of a film.

But there’s a different problem now. The influence of visual media on writers has, to be honest, brought down the quality of literature rather than elevating it.

Kamal Haasan: Definitely.

Jeyamohan: Aesthetics of language is the foundation of writing. Today, describing what you see, without considering linguistic beauty, seems to be a trend. ‘Zero narration’. The style of saying so and so happened as if summarising a scene.

Kamal Haasan: That came in cinema too. Anti-narrative.

Jeyamohan: There’s a scene in my story ‘Elephant Doctor’, where worms eat into the carcass of an elephant. In the Malayalam translation, which I wrote, the doctor holds the worm in his hand and says, “So, you want a whole elephant for a meal?” It may be tiny but it does eat an elephant... That is fiction’s moment. It is not just visual detail.

Language challenge

Jeyamohan: Do you think you can mirror every powerful evocation of a literary work in cinema, to the same extent?

Kamal Haasan: Cinema is a different language. Just as an English translation is a different experience, cinema too is different. If Shakespeare were to get into films today, he would have to attend a screenplay workshop. Kamban too. Like dialect may be lost in the translation of a book, there might be some loss while making a film adaptation too.

Jeyamohan: But you gain something else…

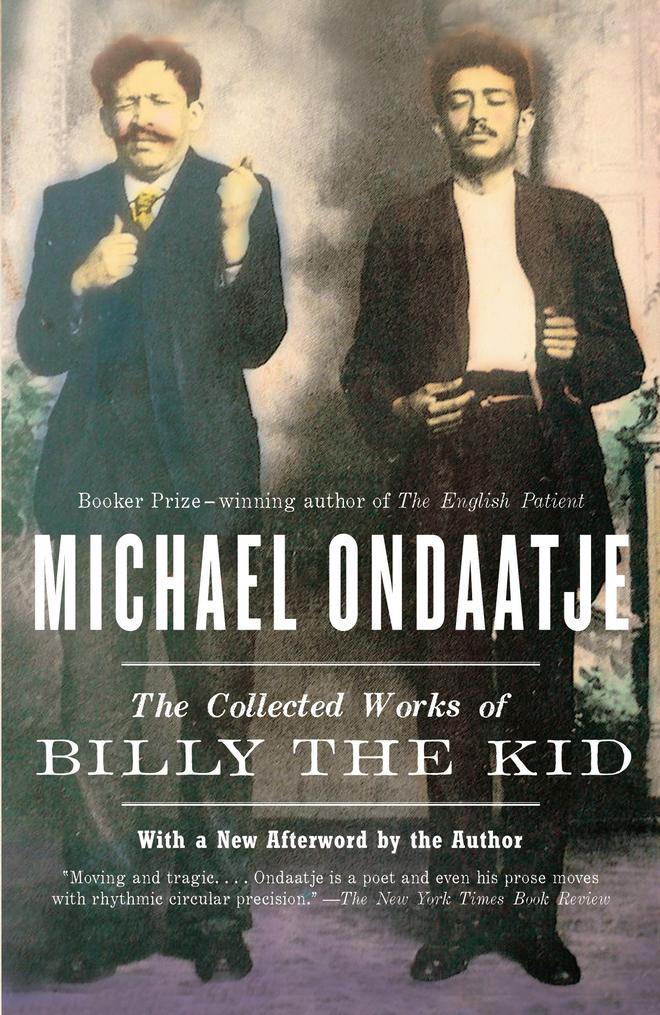

Kamal Haasan: Yes. There’s a scene in Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, which is exactly the same as a scene from Kalingattuparani, of a vulture flying away with the intestines, and the protagonist drawing it back. That astounds me. I don’t know how it got there… Perhaps he read a translation of the Tamil work. Like you heard about the Elephant Doctor’s love for Lord Byron, we somehow hear these stories. Even our conversation today may have an impact on a writer somewhere.

The interview has been translated from Tamil by Priyamvada Ramkumar, who is the translator of Jeyamohan’s Stories of the True (Juggernaut, 2022).