The village of Janwada in Telangana’s Rangareddy district, located 30 kilometres from Hyderabad, looks like a human heart on Google Maps, with its roads and bylanes resembling arteries and veins. Nestled among corporate farmhouses; film shooting sets; and lush tennis, cricket, and equestrian clubs, it is part of a plush area that realtors passionately label ‘the golden triangle of Hyderabad’. It is also a 15-minute drive from the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority’s (HMDA) much-vaunted ₹100-crore-per-acre Neopolis layout, a commercial-residential-retail hub. Luxury SUVs and vanity vans zip through this Hyderabad-Shankarpally road, along which Janwada village is located.

Janwada was to begin its weeklong festivities for the consecration ceremony of the newly-built Ram temple starting February 17, but the entry to the village, through high wooden arches and scaffoldings is now blocked by the police. The LED panels of the village deities remain unlit. The procession of the idols and dedication of the temple’s shikara (crown of the tower), dhvajastambha (flagstaff), scheduled to take place across the week have been put off as well. So have the Bodrai festivities that take place annually at the village’s central stone, around which the homes grow. The village’s two churches have also remained closed since Ash Wednesday last week, the first day of the 40-day period of Lent (preparatory period leading up to Easter).

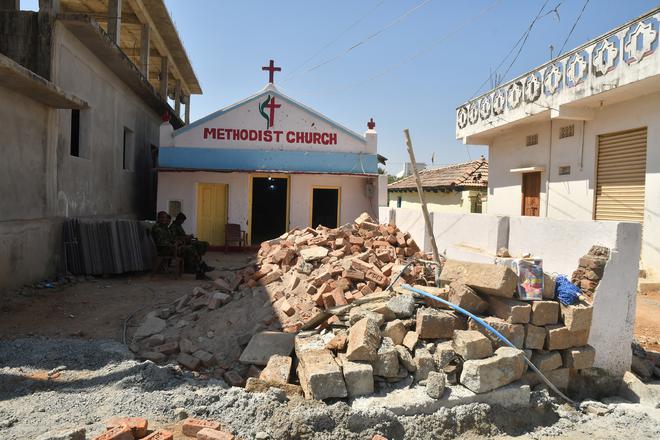

After clashes between two groups of the village on late February 13, allegedly over the issue of road widening, the Cyberabad Police enforced CrPC Section 144 (prohibiting assembly of five or more people) in Janwada from February 14 to February 21. Simmering beneath the civic issue are allegations by church-goers that the village sarpanch’s husband, who had previously supported church-building, was now aligned with Hindu organisations, while they were painted as road encroachers.

Peace disrupted

The prohibitory order has transformed the scene in the otherwise bustling village, which has a registered voter count of about 4,500. The men are nowhere in sight, women cautiously peer from doorsteps, children are at the Zilla Parishad school, and there is a considerable police presence: at the clinic, the real estate office, and across the Methodist Church, in the village centre.

The violence left three severely injured. The police in Shankarpally station say 29 people, including Goudicherla Narsimha, husband of village sarpanch Goudicherla Lalitha Narsimha, whose term ended last month, a former mandal leader, and others were listed as accused. They were booked for rioting, attempt to murder, defilement of a place of worship with intent to insult the religion and outraging religious feelings, under the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989, among others. The FIRs and remand reports do not mention the accused as belonging to any political outfit.

Based on a counter complaint by Narsimha, police also listed 26 Dalits of Meedha Basthi (meedha meaning upper side, in Telugu) as accused, charged with attempt to murder, voluntarily causing hurt by dangerous weapons, unlawful assembly, and rioting.

The complaint states that between 12 and 20 church members disrupted the laying of the road in front of the church, and the autorickshaw and bus stands, despite the issue having been discussed by the villagers and elders. “Krishna, joined by others, pelted stones and bricks from the church towards the public near the concrete mixer. As a result, three persons, Srinivas, Padmamma, and Vivek, sustained injuries,” it reads.

The police arrested and remanded six accused from the sarpanch’s side and five from Meedha Basthi to judicial custody; 44 from both parties were reported as absconding.

Dalit voices

The Methodist Church is the prayer site for 60-odd families of Meedha Basthi, most Dalits, located right behind. The village that has about 18% Dalit population, also holds the Jeevamugala Prarthana Mandhiram, is in Kindha Basthi (habitation in the lower part of the village), eight temples, and a mosque.

Many Church-going Dalits are Scheduled Castes (SC), listed as Hindu in the records. This segment of the population has been generationally discriminated against irrespective of whether they convert out of Hinduism or not. As Dalit Christians and Dalit Muslims fight for the SC status in the Supreme Court, many have chosen not to change their status on paper for fear of being further discriminated against.

The church-goers in Janwada claim that Narsimha had given a donation in 2020. They say his brother, G. Venkatesham, a real-estate businessman and leader of ward 5, equally respected in the area, had donated bricks for the Methodist church’s new building. Villagers say he aspires to become the next Sarpanch, hence he offered the donation seeking support. Church-going families began the construction in 2020 with an agreed contribution of ₹50,000 per family over a period of five years.

Sushma, a primary school teacher, shares that Narsimha, while seeking votes in the 2019 gram panchayat elections, promised to pay for the concrete slabs required for construction of the new church. “We voted for him, and he fulfilled his promise. Just because he contributed money for the church building, he cannot say that he will bring an excavator and demolish the church. Would he say the same thing about the temples for which he had donated money,” she asks.

On the day of the incident, villagers remember three men, bleeding from the head, their limbs covered in cement as they attempted stopping the concrete pour, lying unconscious on the floor of the Methodist church. The doors, as old as the 50-year-old church, had been broken open, allegedly by the attackers. A dozen others, including women and children, who had sought refuge there, had minor bleeding and limb injuries.

“Each time they picked up a brick or a stone and threw them at us, they chanted religious slogans. Some of them were carrying sticks,” says Jyothi (name changed to protect privacy), a resident of Meedha Basthi. She recalls that the men climbed up to the balcony of the adjoining under-construction church in the same compound. “They damaged the cross and the big star. They threw bricks at us through the asbestos roof,” she says, pointing to her bandaged shin. Who were they? “Bajrang Dal youths, along with village elders. There were around 150 of them,” she alleges.

Signs of discord

Janwada, in the thick of the clampdown, still has remnants of the scenes of the jubilation associated with the consecration of the Ram Lalla idol at the Ayodhya temple on January 22, and the preparations for the consecration ceremony of its own Ram temple scheduled during the week. While the videos from the evening of the violence show saffron buntings and flags at the village centre, in front of the B.R. Ambedkar statue and the adjacent church, they were removed the next day. The bust of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, the central statue of the village, from where the flags were secured still bears the saffron tilak.

The wider and more prominent symbol, however, is the stencil paint branding of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ in Telugu on every other house and electric cement pole in the village. The same slogan was embossed on the gate-post of the Muslim graveyard located in a far corner of the village, but it was later struck off using saffron paint.

“Branding of the houses was done during the Ayodhya event last month. They started sloganeering at the same time. Such a thing was unheard of in our village,” says A. Srilatha Ramulu, who until recently was the deputy sarpanch. Houses that attend church were not marked with saffron paint, she clarifies. Although Srilatha’s family does not go to church, her husband was arrested and sent to prison along with other church members. “As far as development works are concerned, there was never any discrimination on grounds of religion or caste,” she adds.

Since the violence broke out, T. Prabhakar, in his 30s, an employee at a private bank in Madhapur, has been shuttling between his home in Janwada and a hospital in Narsingi, nearly 13 km away, to attend to his father, Bikshapathi, 56, the oldest of the three men found bleeding profusely in the church. All three suffered varying lengths of scalp lacerations and physical injuries, Prabhakar says, showing medical certificates.

He scrolls down through the photo gallery on his phone, showing pictures of the old and the new church buildings, with and without the compound wall, various stages of construction, and decoration for Christmas. According to Prabhakar, the church land dimensions are clearly demarcated in the panchayat records, and the demand now was to limit the road-laying to the old compound wall, which was removed to facilitate movement of church construction material.

“It was unanimously agreed upon following discussion with the gram panchayat leaders, but when excavation of the old road started, the first step of the church was flattened. A correction was promised, but they decided to extend it to three feet,” he says, adding that the houses located in front of and next to the church were left untouched. Then, he says, “Someone created a narrative that church members were encroaching on the road and obstructing village development.”

A day after the violence, an engineer of the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA) that was laying the road in Janwada, filed a complaint at the local Mokila police station. “After our engineer made the marking for 24-foot-wide road and left the village, Narsimha from Janwada called and requested us to extend the road up to the church wall. It was denied. The road markings made by our engineer were removed and the workers were forced to lay the road till the church wall, ultimately leading to the damage,” says the complaint, registered by V. Ravinder, deputy executive engineer, HMDA.

Police booked six village leaders and others named in the first complaint for criminal trespass, criminal intimidation, mischief by injury to public road, and under the Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act, 1984.

At the crossroads

President of Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)-Telangana, R.S. Praveen Kumar, who expressed solidarity with Dalits in the church, alleged that the attackers were “RSS, BJP, and Congress goondas”. He was quickly arrested and removed from the limits while attempting to enter the village. His accusation irked the Telangana Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and its youth wing, the Bajrang Dal.

Bajrang Dal-Telangana convenor U. Shivaramulu condemned Praveen Kumar’s statements, while protesting “the illegal arrests of Hindu youths in Janwada” and gave a call for ‘Chalo Mokila’. He was placed under house arrest.

While Shivaramulu was unavailable for comment, his last interview with a YouTuber explains his observations on the Janwada incident. “There was no RSS or Bajrang Dal activist in the Janwada incident. It was a dispute on road encroachment by the church which the villagers opposed. How would someone claim Scheduled Caste status if they change faith?” he says, adding that the SC/ST (PoA) Act not be applied since the Dalits were church-goers. As per Indian rules, only Hindus can claim Scheduled Caste status and the accruing benefits. Anyone who converts out of the religion may qualify to be a Backward Class (BC).

“They ask us how we are Christian with Hindu Scheduled Caste status. They also say we are all Hindus in India,” say a group of women from Meedha Basthi. The women, waiting for the men in the village to return, are fearful of the future. “This kind of violence should stop. We want our village to be peaceful again. Our children should live without grudges, like our fathers and grandfathers did,” says a woman resident, requesting anonymity.

All churchgoers, they are homemakers and work as gardeners, security guards, house cleaning staff, teachers, and school ayahs in Narsingi and Gachibowli localities of Hyderabad. “In my lifetime, I have not seen anything of this kind in this village,” says resident Devamma, who is in her 60s.

Rachuri Ilaiah, a former sarpanch of Janwada and Cyberabad police’s panch (witness) for the February 13 incident, says, “It happened on the spur of the moment, due to a misunderstanding, with two or three youth from each side inciting violence. How come a sarpanch [the accused Narsimha] who is building the church wants to demolish it? How come he sends ₹1 lakh to the church victims for treatment at a private hospital? Those youths would have gone ahead and killed people if not for timely intervention by village elders,” Ilaiah argues.

Back under the high wooden arch, the village entry and exit point on the Hyderabad-Shankarpally Road, a posse of police from Cyberabad commissionerate and the special forces continue to keep vigil and check Aadhaar cards of people wanting to enter the village. People who do not ordinarily reside or have work in the village are prohibited entry.

On the opposite side of the road, Gangadhar and Pramod of Mirjaguda, adjoining Janwada with a common entrance/ exit, were waiting with Aadhaar cards to accompany their relatives into their own village. “What difference will it make if the road was laid or not near the church? The festivities are being postponed because of their fight, and the entire village is suffering,” says Pramod. He reflects the view outside the heavily guarded village where the flow of information too is kept under control, that it was all just a misunderstanding.