Easter in Nigeria is a time when many people traditionally get together with their relatives to celebrate weddings and other festivities, but for Yana Galang, the holiday serves as an agonising reminder of her family’s suffering.

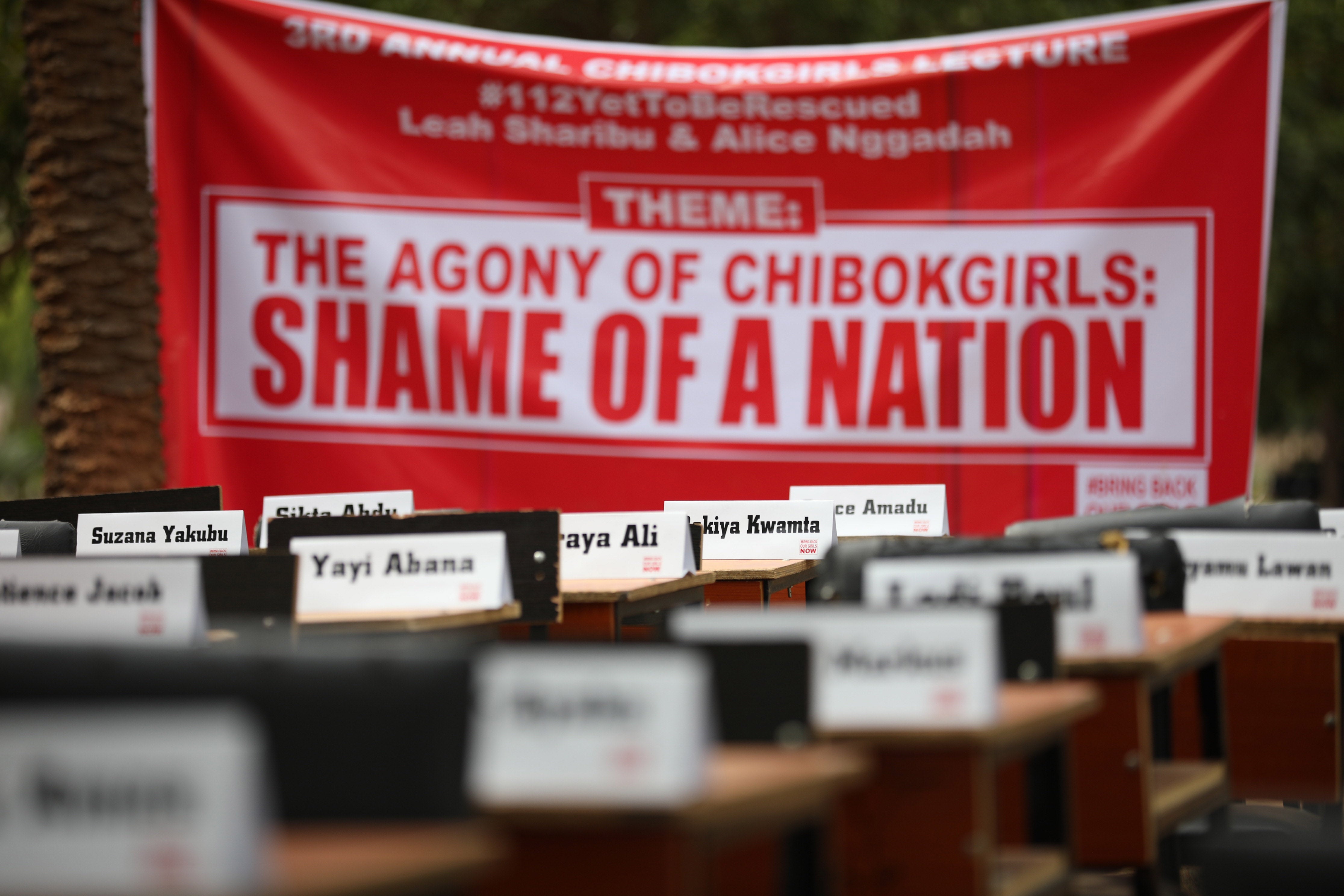

Yet it is an important occassion for her and dozens of other parents to mark the anniversary of and demand action over the kidnapping of their daughters from their school dormitory in the northeastern Nigeria town of Chibok eight years ago

As the women leader of the Association of the Parents of the Abducted Girls from Chibok, Galang has been reaching out to other members of the group, arranging meetings, organising catering, and all the other tasks that go into planning the yearly memorial service.

Her daughter, Rifkatu, then 17, was among 276 girls taken on the night of April 14, 2014. But, while Galang still sheds tears at the disbelief and devastation that her child is still not back home more than eight years later, she knows that the other mothers look up to her for leadership and strength.

“It’s a very sad day again,” Galang told The Independent via phone from her home in Chibok. “Anytime we remember this 14 April, mothers, we are always crying. But it is well. As women leader, I advise them, counsel them not to worry and to only put our hope in God.”

More than 100 girls are still missing and the parents feel let down by the Nigerian government, she added.

In his first term of office, which began in May 2015, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari had met with the association in the capital city of Abuja and promised the parents that he would bring their daughters back home, and it is for this reason that the Chibok community voted overwhelmingly for him during his re-election bid in 2019.

But, less than one year to the end of his second tenure, that promise has only been partially fulfilled.

About 110 of the kidnapped ‘Chibok girls’ were reunited with their parents between 2016 and 2018. Three were found or rescued in the Sambisa forest hideout of Boko Haram by the Nigerian military, while 103 were freed after a ransom of 3 million euros (£2.5 million) was paid by the government following negotiations with militants.

The former captives spent several months undergoing a rehabilitation programme in government custody in Abuja. Afterwards, they were sponsored by the Nigerian government to attend a special education programme at the American University of Nigeria (AUN), Yola, northeastern Nigeria, about 185km from Chibok.

The programme is still ongoing, and Galang, in her role as women leader, is actively involved in the welfare of the AUN students. Along with the chairman and secretary of the association, she attends parent-teacher events at the institution where the rescued girls have their designated residential facility, and chaperones them to and from Chibok at the beginning and end of school holidays.

“But, up till now, more than 100 are still missing,” she said. “We want the government to do something before they put off the garment (of leadership) in the remaining days.”

Yakubu Nkeki is one of the parents whose daughters is studying at the AUN. He feels delighted that she has been freed and is being taken care of by the Nigerian government, but he remains concerned about the parents whose children are still missing.

Nkeki continues to advocate for them in his role as the president of the association, and ensures that the parents of the freed girls still show solidarity by carrying on attending meetings, including the forthcoming anniversary, which will take place at the school premises where the abduction took place.

He hopes that the eighth anniversary will provide an opportunity for them all to speak up with one voice in the hopes that the government would once again be stirred by their plight.

“In more than two years, there has been nothing from the government,” he said via phone from his home in Mbalala, Chibok. “They are no longer communicating with us.”

Previously, top government officials had met regularly with the parents or association’s leadership in Abuja or in Chibok. The federal and state governments also sent representatives to the anniversary events held at the school every April 14, but all that has ceased.

“The government is not inviting me and telling me things like before,” Nkeki said.

Nigeria’s presidential spokesman Garba Shehu said “we have not given up on the rest of the girls”.

"Nobody can give assurances on anything, but the rescue efforts are still ongoing,” he told The Independent.

Meanwhile, the Nigerian government has been grappling with many other cases of school kidnappings.

The Chibok kidnappings in April 2014 drew shock and horror from people around the world, leading to a global Bring Back Our Girls social media campaign for their release that saw the involvement of celebrities and world leaders.

Since then, however, school kidnappings have become more common in Nigeria. At least 1,409 students were kidnapped from their schools in the northern region in the 19 months between March 2020 and September 2021, according to Nigerian intelligence platform, SBM, and at least 220 million naira (£408,000) was paid out as ransoms.

Most of these recent incidents have seen little government involvement, with the parents and relatives left to pay the ransom for their children’s release. The spate of kidnappings, while appearing to be from the Boko Haram playbook, has been attributed by the government and local media to armed gangs commonly described as ‘bandits’.

These bandit gangs, usually with hundreds of men, have in the past two years regularly sprung out of their hideouts in surrounding forests to attack dozens of rural communities across northern Nigeria, leading to the death of hundreds of people and the displacement of thousands.

As for Boko Haram itself, the militants have been in a state of flux due to a conflict with a splinter group-turned-rival, the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP). However, Nigerian officials said last October that Boko Haram had moved into north-central Nigeria in an apparent expansion - and it still presents a serious threat to the government.

Nearly 350,000 people have died due to the group’s 13-year insurgency and ensuing humanitarian crisis, the UN said last year.

However, that figure does not capture the suffering of countless other citizens like Galang. While she may feel disappointed in the government’s response to the Chibok saga, she remains hopeful of her daughter’s release, and her grief this year is slightly tempered with relief.

In January, she received the news that Rifkatu is alive and well, although married to a Boko Haram militant and with two children. She may not have seen her daughter for eight years, but she is happy to know that she is alive.

She received this information from a girl from Chibok who was married to a Boko Haram member, one of many that have recently surrendered to the Nigerian military. The girl told Galang that she spent some days with Rifkatu in a remote town in Gwoza before she and her husband decided to flee and repent.

“She says my daughter is fine but the only thing is that’s she doesn’t have the sense to come out like the girl herself. She said she has two children,” Galang said. “And the man that married her, he doesn’t want her to have anything at all to do with Chibok again.”

"I want to not only hear about her but to see her."