In a pre-dawn raid in November 1990, feds armed with warrants, padlocks, and chains seized everything Willie Nelson owned—his golf course, ranches, studio, all of it. Only one thing slipped through the IRS perimeter: Willie’s guitar, “Trigger.” Thirty-five years later, Willie still has Trigger. Oh, and he eventually got back the ranches, studio, and golf course. These days, Willie Nelson’s nine-hole course—nicknamed Cut ‘N Putt—dances like an old brown shoe through loblolly pines in the Austin hills. The parking lot is guarded by what folks in the music business call “a silver firecracker”—a big Airstream bus that Willie and friends call Honeysuckle Rose. (Willie’s been travelling again, headlining Farm Aid 40 at the age 92 and announcing another, and perhaps final, tour.)

Golf pro Fran Szal, 75 years young, greets all comers with a wry smile. For pilgrims like my wife and I, who have come from afar, he slips into stories as if they’re on his lips at all times.

“They took everything,” Szal recalled on our visit last year, adding with a chuckle. “But not … Trigger. Yeah, we managed to hide that.” We met him near Cut ‘N Putt’s rustic pro shop, which could pass for a set for the 1960s sit-com The Beverly Hillbillies. In a world forever in need of magic, Trigger appears to have its own powers. Rumor has it that Willie’s daughter aided its escape. But when pressed, Szal says only: “The family likes to keep some things to themselves.”

The fact remains: On the day the feds came to shut Willie down, Trigger somehow slipped out of bed, made it to the golf course, travelled by mail to Hawaii, and hid out until Willie got his house and taxes back in order. (Willie’s daughter Lana may have something to do with getting the postage right.) Of all the blessings in the world, the fact that the federales missed Trigger seems to be a story that is winning the fight with infinity.

Trigger had accompanied Willie’s soft twang on “Stardust,” the now triple-platinum 1978 album that brought the mainstream to country. Can you look at the endless sky in these hills and not hear Willie’s voice singing Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies”? Willie wrestled that immortal song into our mortal world, his fingers caressing Trigger, the very instrument that birthed so many iconic tunes: “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground” (1980) ; “Always On My Mind” (1982) ; “On the Road Again” (1988).

My wife Monica and I had different reasons for journeying to Pedernales. She’s a fan. But our visit to Willie’s golf course was partly for my research on a book on Native-owned golf courses. (Formally, the course is called Pedernales, but its nickname is Cut ‘N Putt.)

It’s a little-known history I was working to unearth. The Osage built a course in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, during the oil boom, which no longer exists. The Mescalero Apache’s course at The Inn of the Mountain Gods in New Mexico, built in 1975, remains a cherished masterpiece. With the advent of gaming, in 1988, more than 60 tribes, bands, and nations built courses.

Some, including me, count Cut ‘N Putt, purchased in 1979, as yet another early Native-owned course. Willie Nelson, after all, was twice named Outstanding Indian of The Year by the American Indian Exposition. In 2014, he and Neil Young were presented with buffalo robes for their work with Farm Aid and the Keystone Pipeline protests by the Oceti Sakowin, Ponca, and Omaha nations.

But, as it is for others who believe they have Native roots in Arkansas and Texas (the states where Willie’s family lived), proof can be elusive. Nelson is on record saying his mother—Myrle Marie Greenhaw Harvey Nelson—was three-quarters Cherokee. In the Story of Texas, the Bullock Texas State History Museum reports this as fact.

In an interview reported in The Encyclopedia of Arkansas, however, Nelson’s mother’s sister, Sybil Greenhaw Young (1923–1999), claimed it was her mother, Bertha Greenhaw (Willie’s grandmother), who was three-quarters Cherokee. In the same interview, Young also said her grandmother (Willie’s great-grandmother) was “full-blooded Cherokee” and that Willie’s great-grandfather was “half Cherokee and half Irish.” The encyclopedia separately reports that while Cherokees were known to live in that same area, Willie’s maternal grandparents were listed in U.S. Census records as white.

None of these ancestors appear in the Dawes Rolls, a historic federal record from 1909 to 1914 that documented the enrollment of members of five tribes including Cherokees, and neither they nor Willie have ever been a citizen of the federally recognized Cherokee Nation, which enjoys tribal sovereignty and determines its own membership. Willie himself was born the year before the The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the New Deal act (written by John Collier) that led most tribal constitutions in ensuing decades to develop a criteria for claiming Native heritage.

Given this history, and considering the social milieu that Willie came out of, it is perhaps not surprising that the Greenhaws and Nelsons did not formally demonstrate descent from an enrolled ancestor. Nevertheless, as late as a 2024 interview with Robert Sheer, Nelson again recounted the family stories that establish, for him, his mother’s Cherokee ancestry. Given this, the accolades from the tribes themselves, and Willie’s embrace of Native causes, I include Cut ‘N Putt as an early Native-owned golf course and one worth our pilgrimage.

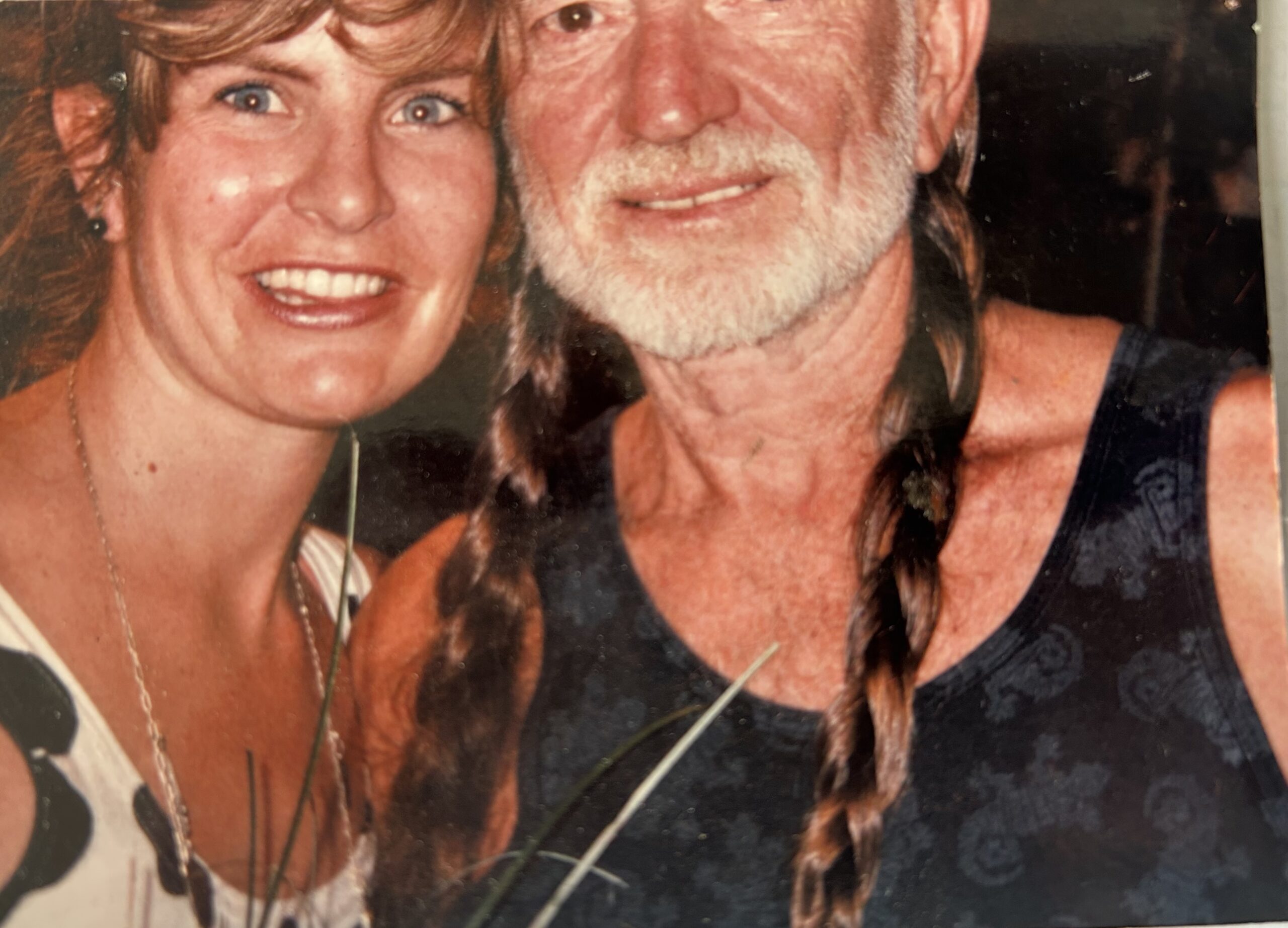

Regarding Willie’s ancestry, something firmly established is that he comes from a long line of musicians. And that was the other reason for our visit: my wife’s love of his music. In the rustic clubhouse, my bride, Monica, took out her phone and showed Szal the snapshot she keeps of her and Willie. They met at the South Shore Music Circus in Cohassett, Massachusetts, in 1992. “Back when he was younger,” she said.

Szal smiled. In the photo her beautiful face is tucked into Willie’s shoulder. He is wearing a red bandanna. Her smile is as wide as Texas. “I asked him who was the first one to sign his guitar,” she told Szal. He raised an eyebrow. “Leon Russell,“ she said excitedly. Szal nodded then and gave her a golf shirt. The logo? Trigger, of course.

Willie has said that the tone of Trigger is “beyond explanation.” After his Baldwin acoustic was damaged—in 1969, in circumstances that may have involved Merle Haggard and drinks—Willie bought the nylon string Martin N-20 from a luthier in Nashville named Shot Jackson. He had Jackson take the electronics from his busted Baldwin and install them in the Martin, and Trigger was born as what musicians call a Frankenstein, an instrument made of different, divergent parts.

Szal waved us out the door into a brilliant, winter sun. When asked if Willie is any good at the maddeningly difficult game of golf, he said diplomatically: “Willie plays ‘Feel Golf.’” Then he pointed past an unkempt fairway to where Willie built a studio, the very studio the Feds seized and had to return. Szal explained how Nelson’s working method became “cut and putt.” Cut a track, then play nine while the mixers mixed. Cut a track, then putt. Then do it all again. The first work produced in this golfing method of making music? Tougher than Leather, the 1983 album anchored by the hit “Pancho and Lefty.”

I asked Szal to clarify what he meant by “Feel Golf.” After showing another group of pilgrims to the first tee, Szal directed us to Willie’s rules, hand painted on some burlwood. Among them:

Par is what you set it at.

No more than 12 in your 4-some.

Missing balls are considered stolen. (No penalty.)

Bikinis Ok.

Szal, my wife, and I stood there laughing in the clear light.

Willie and Trigger slowly won their battle with the IRS: He paid off back taxes, partly by releasing more songs under the title Who Will Buy My Memories? And Willie’s stuff came back to him—the Austin ranch. The Utah ranch. This studio and golf course, where Trigger would do its best work.

Given the seemingly supernatural powers of that six-string, I asked Szal how many years before Feel Golf would become the standard of play, when bikinis are ok and all lost balls would be considered stolen?

He wouldn’t venture a guess, but I came away convinced. In the end, we’d all be better off playing by Willie’s rules.