This story is a collaboration from Floodlight and was also published in the Guardian and the San Antonio Report.

When the city of Austin drafted a plan to shift away from fossil fuels, the local gas company was fast on the scene to try to scale back the ambition of the effort.

Like many cities across the US, the rapidly expanding and gentrifying Texas city is looking to shrink its climate footprint. So its initial plan was to virtually eliminate gas use in new buildings by 2030 and existing ones by 2040. Homes and businesses would have to run on electricity and stop using gas for heat, hot water and stoves.

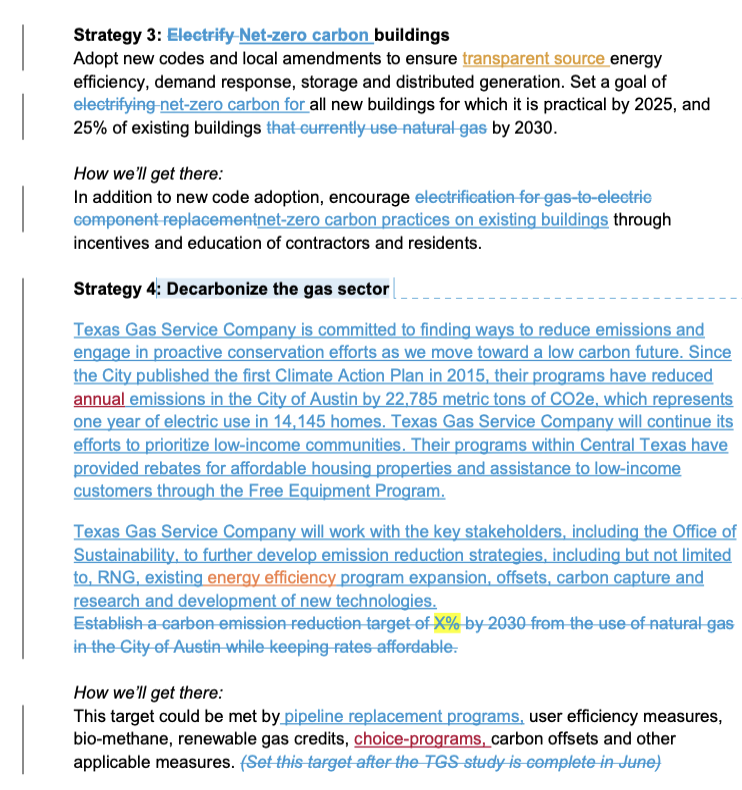

The proposal, an existential threat to the gas industry, quickly caught the attention of Texas Gas Service. The company drafted line-by-line revisions to weaken the plan, asked customers to oppose it and escalated its concerns to top city officials.

In its suggested edits, the company struck references to “electrification”, and replaced them with “decarbonization”– a policy that wouldn’t rule out gas. It replaced “electric vehicles” with “alternative fuel vehicles”, which could run on compressed natural gas. It offered to help the city to plant more trees to absorb climate pollution and to explore technologies to pull carbon dioxide out of the air – both of which might help it to keep burning gas.

Those proposed revisions were shared with Floodlight, the Texas Observer and San Antonio Report, by the Climate Investigations Center, which obtained them through public records of communications between city officials and the company.

The moves have so far proven a success for Texas Gas. The most recently published draft of the climate plan gives the company much more time to sell gas to existing customers, and it allows it to offset climate emissions instead of eliminating them. The city, however, is revisiting the plan after a backlash to the industry-secured changes.

The lobbying in Austin is not unique. It echoes how an electricity and gas company spent hundreds of thousands of dollars scaling back San Antonio’s climate ambitions by funding the city’s plan-writing process, replacing academics with its preferred consultants and writing its own “Flexible Path” that would let it keep polluting.

The American Gas Association in a statement for this story said it “will absolutely oppose any effort to ban natural gas or sideline our infrastructure anywhere the effort materializes, state house or city steps.” But it argued that position is “not counter to environmental goals we all share”, and said “natural gas is key to achieving the cleaner energy future we all want.”

Texas’s reliance on gas was on display in mid-February when more than 4m households lost power for days after a freak winter storm battered the state. Gas power plants dominate the Texas grid, providing 47% of the state’s electricity. Many of those plants and the natural gas pipelines leading to them failed in the cold conditions.

More than a third of Texas households also rely on gas for heat. Competition for gas-fueled power and heat forced prices to surge as high as 16,000%, one power company said. Utilities now face massive bills from their gas suppliers – and many are passing the costs on to customers in the form of sky-high bills.

The CEO of Comstock Resources, a gas company owned by the billionaire Dallas Cowboys owner, Jerry Jones, described the gas industry windfall as “hitting the jackpot” in an earnings call.

A nationwide fight goes local

The gas industry is battling climate change reforms in cities around the US – with support from Republican politicians.

In Texas, lawmakers have introduced two bills that would prohibit local governments from banning gas connections. “There hasn’t been a city necessarily that has banned natural gas yet, but we have whispers from the Austin city council, the city of Houston, even smaller cities,” said Jeff Carlson, the chief of staff for Representative Cody Harris, who introduced one of the bills.

Four other state legislatures passed similar laws last year, and 12 more have seen proposals for them in 2021. The gas lobby, the American Gas Association, has said it isn’t actively coordinating support or lobbying for state laws to prohibit gas bans, but its internal records indicate a different story.

“We are increasingly active in the States,” the association’s president, Karen Harbert, said in a November letter to members explaining how the organization spent membership dues in 2020. She said the association is participating in several “Pro Natural Gas Coalitions” to bring allies together.

“Over the course of the year, legislation preserving energy choice for customers passed in Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Tennessee,” Harbert said.

Another internal association email in February 2020 shows the senior director of state affairs, Daniel Lapato, asking a publicly-owned gas utility to back the Tennessee bill that ultimately passed.

The gas burned in buildings causes about 12% of US climate pollution, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Cities are trying to shrink those heat-trapping emissions with building codes and mandates to switch from gas to electric appliances.

In Texas, they could have a significant impact. Texas burns far more gas than any other state, 14.9% of the US total.

Gas is cheap, and affordability is a major concern in Austin, where families and people of color continue to get priced out of the fast-growing city.

But even so, Austinites don’t necessarily want gas, said Chelsea Gomez, a community ambassador who consulted on the city plan. “When you talk to people, they don’t want natural gas as a middle man to a sustainable future – they want solar panels to be affordable for them,” said Gomez. “People want better [options].”

Burning gas indoors exposes people to dangerous pollutants that are linked with heart attacks, respiratory disease and asthma. One study found that children in homes with gas stoves were 42% more likely to have asthma than children in homes with electric stoves.

The fossil fuel also has clear climate impacts. In Texas, the number of days that are 100F or hotter has more than doubled over the past 40 years and could double again by 2036, according to a study from the Texas state climatologist. Extreme rainfall and urban flooding are increasing, hurricanes are getting more intense and the Gulf of Mexico is rising. Droughts and wildfires are becoming more severe.

Those effects were what Austin was trying to help to limit when Texas Gas Service got involved.

‘Crashing the party’

After one early meeting in June with the city’s climate program manager, Texas Gas’ regulatory affairs manager, Larry Graham, said in an email to Austin’s climate program manager, Zach Baumer, that the proposal for all-electric new construction had “gotten the attention of people at the highest level of our company.” The city released the internal emails, along with the draft versions of the plan, in response to a request for public records.

By July, employees of the company’s parent corporation, One Gas, were weighing in on the proposals from their headquarters in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

It was a level of involvement that raised red flags among city employees.

Baumer later emailed Graham that his company was “kind of crashing a party” when it attended meeting after meeting.

Still, the city officials listened to Texas Gas’ feedback. The climate plan originally called for completely eliminating natural gas use in all buildings by 2040. A few months after the gas company’s lobbying efforts, the city moved the goalposts: Only 25 percent of existing buildings would need to transition off gas by 2030, although all new buildings would have to be off gas by then too.

Texas Gas would be allowed to offset its pollution, by purchasing credits for climate work elsewhere in the country, upgrading leaky pipes and using ‘renewable’ gas from a wastewater treatment plant – efforts which environmental advocates said weren’t enough.

The steering committee was incensed, according to a handful of participants interviewed. The members were selected from the community to focus on equity and write an ambitious plan, but the industry was already thwarting them.

Baumer said he quickly realized his mistake.

“Everybody was pissed at me. I had to call and apologize to people because we sort of gave into what Texas Gas wanted,” Baumer said. “I thought I was making a compromise position. The people who were part of the plan didn’t think that.”

Shane Johnson, the co-chair of the steering committee who works for the Sierra Club, called Texas Gas’ influence “unnerving.”

After environmental advocates balked at the revisions, the city agreed to revert back to the original, more aggressive goals.

Texas Gas, when asked for comment, said it was “invited to participate in the revisions to the Austin Climate Equity Plan and [has] remained an engaged partner ever since.” The company said it has participated in Austin climate initiatives since 2014 and shares the aspiration of reducing carbon emissions.

“We believe that by working together we can improve our community and create effective, long-term strategies that reach the city’s sustainability goals in an equitable and affordable manner for all residents,” Texas Gas said.

In September, when the company seemed to be losing the fight over the proposal, it sent an email to customers claiming it would “severely” drive up costs and “threatens to take away the rights of people to choose their source of energy.”

San Antonio

In San Antonio, local business interests – from the city’s utility company to car dealerships – were even more successful in scrubbing language that called for a full transition away from fossil fuels.

CPS Energy, the city-owned utility that supplies power and gas to San Antonio, spent $650,000 to fund the climate planning process and helped put its preferred consulting firm in charge instead of faculty at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

As committees were meeting in 2018, CPS Energy leaders announced they had already developed their own plan for the coming decades, called the “Flexible Path”. It called for CPS Energy to get half its energy from wind and solar sources by 2040, while also continuing to operate its coal plant into the 2060s.

A draft plan in 2019 refused that approach, but the utility kept pushing back. In April 2019, CPS CEO Paula Gold-Williams called for an “in-depth cost analysis”. In a letter to San Antonio’s chief sustainability officer Doug Melnick, she suggested the draft would be too costly for customers and might jeopardize grid reliability. She won. The next draft in August 2019 adopted CPS’s “Flexible Path”. It didn’t attempt to address one serious flaw: the “Flexible Path” wouldn’t get San Antonio to its goal of being carbon neutral by 2050.

CPS did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.

In response to the lobbying, the city’s final plan watered down key emission goals, replacing specific strategies to cut emissions with vague and sometimes misleading platitudes.

The climate activists did have some successes. They got the city to include interim goals – to cut climate pollution 41% by 2030 and 71% by 2040 as checkpoints on the path to carbon neutrality by 2050.

Greg Harman, a clean energy advocate with the Sierra Club who served on one of the climate plan committees, said Texas’s reputation as hostile to climate action is both earned and imposed on the state by the energy industry. Like the rest of the U.S., surveys show a majority of Texans believe that climate change is real and a cause for concern.

“We’re a complex and interesting state, we just happen to have a lot of energy resources,” Harman said. “But the cynics are right to be cynical.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

Nine Texans on How They Survived a Frozen Week: After an unprecedented freeze swept Texas, the state’s grid approached a catastrophic blackout. Millions of Texans lost power or water—or both.

-

The ‘Culture of Violence’ Inside Austin’s Police Academy: Recent audits of the city’s cadet training spotlight a warrior-cop culture that pervades policing, even in a so-called progressive city.

-

Why Texas Wasn’t Prepared for Winter Storm Uri: A disaster management expert weighs in on how poor planning and communication failures deepened the crisis that left millions without power during the deep freeze.