At Namita Jaspal’s lab in New Chandigarh, a township just outside the eponymous State capital of Punjab and Haryana, lies a piece of leopard skin on a table. “It has come for restoration from a private collection,” says Namita, the chief conservator of Heritage Preservation Atelier, a company she started in 2011.

There are old paintings in the lab too, but Namita’s work takes shape outside — in the wall paintings of 16th-century Golden Temple in Amritsar, 18th- and 19th-century temples built by Maharaja Ranjit Singh across Punjab, and a nine-foot flag gifted by the Chinese to the British Indian Army in the 1800s. “In 2013, I conserved the wall paintings at Golden Temple. It took three-four years to complete the project as there is a lot of footfall. We have also done frescos and wall paintings in temples from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s time. In all of them, there was an amalgamation of faith. In a Krishna temple, there were paintings of all 10 Sikh gurus,” she says.

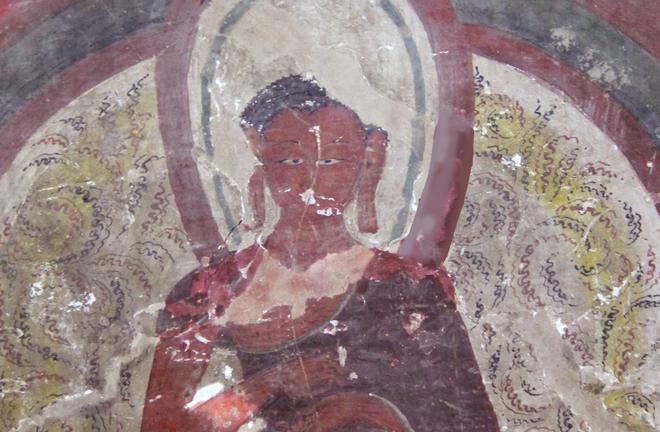

Namita is among the people who are bridging the gap between art and history in India, work which includes wall paintings and murals spanning several centuries. Nilabh Sinha, principal director of Delhi-headquartered INTACH Conservation Institutes, has dabbled in much older wall paintings. He restored those on Ladakh’s 12th-century Mangyu temple complex. Nilabh, who also conserved nine oil paintings of the Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2008 and 2009, says it took three-four years to finish work on the paintings and the structure of the complex. “The original paintings at Ladakh had gold and natural pigments, but they had been overpainted garishly over the years by locals. The structure is made of mud, so the paintings and the structures had been damaged because of the roof leaking during heavy rain,” he says.

Nilabh’s team also repaired, conserved and restored the complex’s structure. He says they employed locals and trained them to continue preserving the monastery. “Local monks too were involved in our project,” says Nilabh, who has also restored the 19th-century limestone Flora Fountain in Mumbai.

Sreekumar Menon, a freelance painting conservator, was involved in the conservation project of Sumda Chun in Ladakh, which was awarded for excellence by UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation in 2011. “We started in 2006 and continued up to 2010,” he says.

In places like Ladakh, where winter temperature drops to -20°C, work is not possible in winter. “There is more rain in Ladakh now, so it gets tougher. In all, we could for 10 months in a year,” adds Nilabh.

In both the projects in Ladakh, the biggest challenge was removing soot which had discoloured the paintings. For Sreekumar, work in Sumda Chun was the most enriching. “During the initial two-three months, there was no electricity. It was interesting to work without a mobile connection,” he says.

Sreekumar says the guiding principle for an art conservator is staying true to the art. “The main thing is how much one could preserve a work of art,” he adds.

The profession, a passion for most who pursue it, pays well too, adds Sreekumar. “If there is no funding, you cannot actually do what you want to do,” he says. Sreekumar has also worked on private collections. When asked about the price it could take to restore a painting or structure, Sreekumar says it depends on the project. “You could need team members for some projects too. But, by an estimate, the price could go up to ₹20 lakh to ₹1 crore for a month,” he says. “There are many variables — logistics, lodging for team, materials and many more. It is highly demanding to work on a site. Sumda Chun is among them: difficult, but rewarding.”

The temple was listed as one of the 100 most endangered sites in World Monument Funds 2006 Watch List, along with three other Indian sites — the 17th Century Dalhousie Square in Calcutta, the 15th-century Dhangkar Gompa in Himachal Pradesh, and the 19th-century Watson’s Hotel in Mumbai.

Sujatha Shankar, who specialises in architecture, planning, and restoration and conservation, is the convener of INTACH’s Chennai chapter. She is also on the governing council and executive committee of INTACH. She had restored a bungalow which was over 100 years old and had colonial vernacular architecture. “The structure had been leased out to Sri Krishna Sweets. We put back light fixtures and preserved the flooring,” she says.

Sujatha has been practising for 39 years. She has mostly worked in Chennai, restoring and conserving structures dating to the British era. Challenges have also involved bringing modern utility to structures built over a century ago.

Recently, Namita restored 17th Century Sikh warrior Banda Singh Bahadur’s angrakha, a piece of clothing. “We used needle and a transparent thread for it, and a weaker adhesive, so that it is removable,” she adds. Golden Temple, she says, was a huge learning experience. “I needed artists, but had to make it clear that they did not have to show their artistic skills, but just fill the gaps from where the paintings were chipped off. They could not use any material; we had to tell them what pigments they needed to work with,” she says. “You cannot make new art on something that has already been made; that’s one of the key points of restoration.”