A psychiatric body makes a belated and bungled apology over child torture in the 1970s. David Williams reports

For something more than 40 years in the making, how did it go so wrong?

Last week, the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists posted an apology on its website for “the harm experienced in state care”.

This was done quietly, almost furtively, without approaching survivors or advocate groups, who called for an apology last year.

No one at the college was quoted by name in the statement, which only mentioned Lake Alice – the notorious psychiatric hospital – once, almost in passing.

“We acknowledge and apologise for the pain that placements in state care, including those at Lake Alice, caused people. We condemn any unacceptable behaviour by individual psychiatrists.”

Perhaps they were referring to one of their own, the late Dr Selwyn Leeks, who instigated the brutal punishment regime at Lake Alice’s child and adolescent unit, which was closed, under a shadow, in 1978.

For years, the psychiatric fraternity closed ranks and backed Leeks, though not always his methods.

These methods have twice been called torture by a United Nations committee, and last year police charged former hospital worker John Richard Corkran, 90, with mistreating children at Lake Alice between 1974 and 1977, by injecting drugs as punishment.

(Corkran, who faces eight charges, has pleaded not guilty.)

The hundreds of youngsters admitted to the unit were often troubled but not always mentally ill. They were certainly traumatised when they left, by being trapped in a state-run facility where electrocution as punishment was routine, seclusion was standard, and sexual abuse rife.

Juxtapose the torturous regime against the college’s jarring apology, and you can understand the heated reaction.

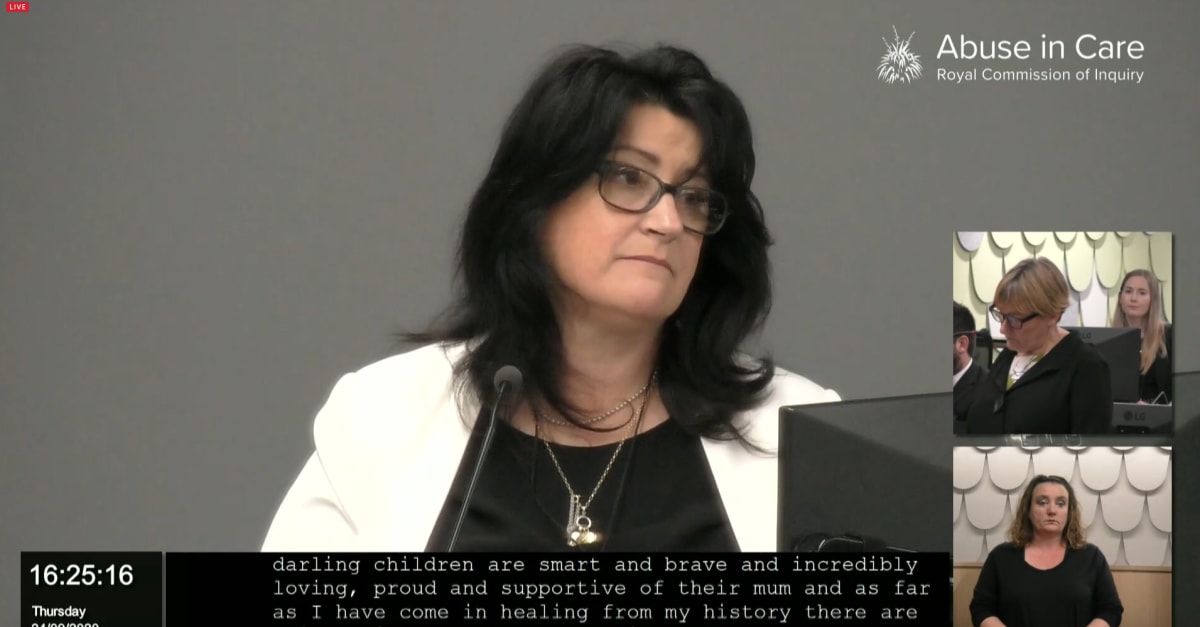

“For a profession, whose main skillset is the use of words, this is an awkward and embarrassing failure of an attempted apology,” Lake Alice survivor Leoni McInroe says.

The college claims to support the Abuse in Care Royal Commission, but, McInroe says, it refuses to be “authentically transparent, honest about their shepherding Dr Leeks to his grave, protecting him from the accountability of the enormous trauma and harm he has caused”.

(Leeks died earlier this year.)

“The offerings of these words simply reiterate the distasteful code of self-importance and protection of their own,” McInroe says.

“I feel sickened and insulted by this entire article. Would any of them accept that as an apology if it were their own child? I think not.”

Paul Zentveld, an Auckland fishing skipper whose case to the UN’s Committee Against Torture was upheld in 2019, asks: “Do they think that’s all they need to do?”

The apology is a start, he says, but the college isn’t off the hook regarding accountability.

Another survivor, Malcolm Richards, of Hastings, had his UN complaint about torture at Lake Alice upheld last month.

He dismisses the college’s apology as a “weak, pathetic waste of words”.

Richards wouldn’t have been aware of the apology had it not been pointed out to him. How can the college take responsibility if the apology isn’t directed at those who should hear it?

“It makes me feel so angry that we are valueless to them.”

The Royal College’s president, Associate Professor Vinay Lakra, of Melbourne, explains via email it wasn’t able to appear formally at the Royal Commission hearings in Auckland because of Covid-19 restrictions.

“As a consequence, we thought it appropriate to issue a holding statement to signal that we take this issue seriously, condemn harmful practices and issue an interim written apology to survivors and their whānau.”

That’s quite a comment – a “holding” statement suddenly, and quietly, appears a year after the hearings concluded, eight months after an apology was requested, and seven months after the Royal Commission’s interim report was made public.

Also, it’s surprising an apology “to survivors and their whānau” shouldn’t find its way to the survivors or their whānau.

“The RANZCP will continue to work towards truth and healing,” Lakra declares.

The findings and recommendations of the Royal Commission’s Lake Alice-specific inquiry will be handed to the Governor General before Christmas.

Lakra says the college (RANZCP) has worked closely with the commission to provide evidence and information. Once the recommendations are released, the college will “carefully consider and act” on them, he says.

“The RANZCP’s work on this issue is far from over,” Lakra says. “There are many important steps in understanding and recognising the undoubted trauma experienced by the survivors of abuse, their whānau, and any others suffering from this harm experienced in state care.

“Although we cannot reverse what has occurred, we can strive to prevent anything like this from happening again.”

Perhaps an important step in understanding and recognising trauma is striving to deliver an apology in a way that doesn’t make survivors “sickened and insulted”, and “angry”.

As always with Lake Alice, the historical context is important.

Newspaper stories started emerging about the mistreatment of children at the child and adolescent unit in 1976, prompted by the work of the Auckland Committee on Racism and Discrimination, or ACORD.

As we know now, several Lake Alice children, including Richards, were shocked on their genitals by an electroconvulsive therapy machine, as punishment for what was considered bad behaviour.

Complaints from whistleblowers prompted several public inquiries.

Oliver Sutherland, of ACORD, who now lives in Nelson, says the Royal College was represented at the inquiry by Magistrate William Mitchell in 1977.

In August of that year, Sutherland attended the annual meeting of the college’s New Zealand branch, in Auckland. “I made it very clear to them just what was going on at Lake Alice.”

He adds: “They’ve known about it for the best part of 40 years.”

(Ombudsman Sir Guy Powles found a “grave injustice” had been visited on a 15-year-old patient who was unlawfully detained, and given electric shocks without consent.)

“They knew it was punishment.” – Mike Ferriss

The first police investigation was closed in January 1978, after they failed to find evidence of criminal misconduct. (Last year, police said they had enough evidence to charge Leeks, had he been mentally fit to face a trial.)

A month earlier, in December 1977, deputy police commissioner Bob Walton had been sent a confidential memo by psychiatrist David McLachlan, a former director of psychiatric services at the Wellington Hospital Board.

The Lake Alice children were, McLachlan wrote, “regarded as hopeless and beyond control”, and “as tough, therapeutically recalcitrant, and morale-destroying [group] as could be assembled anywhere”.

Allegations against Leeks and his staff were unsubstantiated, McLachlan said. And while “unorthodox” methods were used, they had precedent, and none reached the threshold of unethical or unprofessional conduct.

Allegations of “ill-motivated practices” would be “entirely out of character” for Leeks, the memo said.

“Colleagues who know him much better than I do, accept him, as a man who is compassionate, concerned for his patients, and working diligently for their wellbeing.”

ACORD’s Sutherland sits on the Royal Commission forum, a monitoring group he describes as a critical friend of the commission, which, last year, called on the college to apologise.

The college has had every opportunity to make amends for the McLachlan report, Sutherland says, including, most recently, at last year’s Royal Commission hearings. (Leeks’s lawyer attended from Australia via video link.)

Another group that has advocated on behalf of survivors since the 1970s is the Citizens Commission for Human Rights (CCHR), a group aligned with the Church of Scientology.

CCHR’s New Zealand director Mike Ferriss, of Auckland, says the college’s apology is appalling for its lack of context. It doesn’t mention Leeks, or the fact police now say it had enough evidence to charge him. The statement also doesn’t condemn the psychiatric treatment given to Lake Alice’s children.

“It was psychiatric treatment; it wasn’t just an invention of Dr Leeks. That’s evidenced by the number of psychiatrists who backed up Leeks at the time of the early inquiries, and defended him, and defended the Royal College.”

He adds: “They knew it was punishment.”

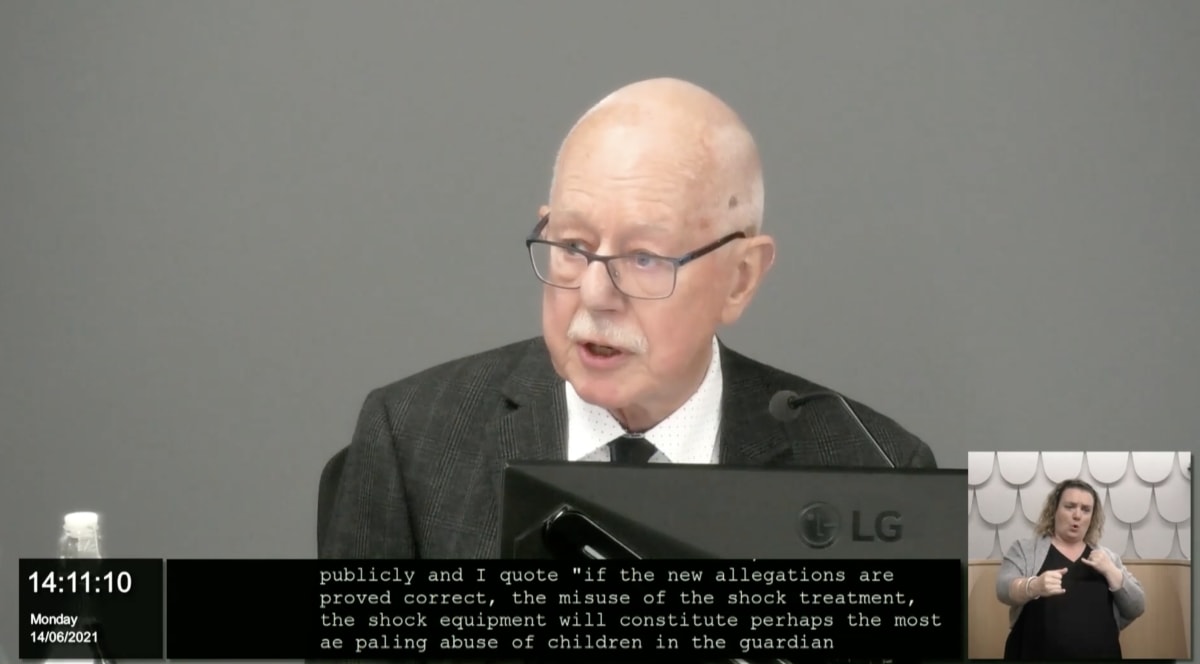

The college has made bold statements in the past.

In the wake of the Government’s apology, and settlement payments, to the children of Lake Alice in 2001, Louise Newman, chair of the college’s faculty of child and adolescent psychiatry, said: “The practices alleged can only be described as severe child abuse and torture.”

The college’s executive director Craig Patterson noted the apology and payments. “And yet, despite previous appeals by the college, no investigation into the role played by this doctor in the alleged practices has been successfully completed.”

In a 20/20 documentary, Patterson distanced itself from Leeks’ regime, saying if the allegations were proved to be true he “shouldn’t be a doctor at all”.

“It is torture. It is terror.”

(For his part, Leeks told Australian media in 2001 the shock treatment at Lake Alice, and use of the drug paraldehyde, mostly administered by nurses, were appropriate.)

Yet, an apology from the college wasn’t forthcoming. Leeks wasn’t investigated by the Medical Council, because he de-registered. In fact, he left New Zealand for Australia in the late 1970s with a Certificate of Good Standing from the council.

Victoria’s Medical Practitioners Board investigated Leeks for seven years, but dropped its formal proceedings after he surrendered his Australian medical licence.

Leeks died without facing what survivors would deem justice.

Given the flood of apologies at the Royal Commission hearings, the survivors and their advocates are left weighing their authenticity, and whether those bodies, faced with similar circumstances, would act differently.

Sutherland, of ACORD, feels the college’s apology is important.

“It gets right to the heart of who was doing what to the children. It was a member of their college [who instigated the electric shocks], and other members of their college who supported him.”

The college didn’t consult the Royal Commission forum before posting its apology, Sutherland confirms.

“After all these years, and after all the revelations at the Royal Commission's hearings – after all of that, if this is the best that they can come up with, then it is just extremely disappointing.”

McInroe, the Lake Alice survivor, knows a thing or two about apologies, having received a fulsome one from Solicitor-General Una Jagose.

In many instances during McInroe’s nine-year civil claim, Crown Law made unacceptable moves, Jagose said at the Royal Commission hearings last year.

“We did not treat you with respect and dignity, we caused additional trauma with what was already a very difficult part of your life.”

McInroe feels the college’s apology is of a different ilk.

“The ‘footnote apologies’ offered up in their news releases to the children of Lake Alice continue to diminish and minimise the voices, the stories, the harrowing experiences the children of Lake Alice were subjected to. It is utterly shameful.”