Eleanor Oliver and her husband had been married for less than a year, she recalls in "The Janes." He was still in graduate school, making her the sole breadwinner for the two of them. "And there I was, pregnant," she says.

In the 1960s, pre-Roe v. Wade, going through with this unplanned pregnancy would have ended Oliver's ability to support them. Managers didn't want pregnant women in their offices. Forget trying to find a job if you had small children at home, she said.

Another woman simply remembered she had no other options, and she wanted her pregnancy ended by any means necessary. An acquaintance connected her to the local mob, who spoke in code: Did she want the "Chevrolet," the $500 abortion option, the "Cadillac" or the $1,000 option, the "Rolls Royce"? She could only afford the Chevy, which left her bleeding in a motel room in an unfamiliar part of town.

"The Janes" is full of such accounts, as well as testimonials from medical professionals who saw firsthand what desperate people will do when they think they have no choice.

RELATED: GOP may get rid of Roe — not abortions

One doctor who worked at Chicago's Cook County Hospital in the pre-Roe v. Wade era estimates the hospital's septic abortion ward was full every day.

That motivated a group of Chicago women to do something, forging an underground network that assisted women of all economic, social, and racial backgrounds and ages to end their unwanted pregnancies regardless of whether they had the means to pay.

When an anxious need is only met by a void, someone or something is going to step in to fill it.

"The Janes" and its eponymous subjects, a group of Chicago women who went by that name to protect their identities and families, are in their way a consolation. When an anxious need is only met by a void, someone or something is going to step in to fill it. These women did that for the sake of other women, with great care in some ways and recklessly in others.

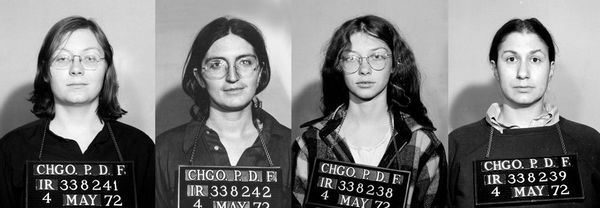

"Pregnant? Need help? Call Jane," read ads they placed around the city, trusting that the people who needed them would notice and the law, mainly overseen by men, would not. And they were successful, until the cops raided the South Side apartment out of which they were operating and arrested seven members in 1972.

While most abortion and reproductive rights advocates don't expect the days of back-alley abortions to return in full force, the main point the documentary makes is that women who want an abortion will find a way to get them. That doubles as an assurance and a warning.

Directors Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes permeate "The Janes" with unforced wry humor that adds a triumphant glow to a story that other filmmakers may have presented as a grim struggle. Then again, the spirit animating these women as they talked about their outlaw days in Richard J. Daley's Chicago in the late '60s and early 1970s makes that seem impossible.

Some were already activists who were fed up with the way the anti-war and civil rights movements sidelined women.

Some, like Oliver, had experienced the pain and terror of illegal abortions themselves, recalling the agony of enduring butchery without anesthesia. Some had simply witnessed someone else's nightmare, or dealt with dismissive medical professionals who shamed women, including rape victims, for their undesired pregnancies, assuming the fault to somehow be theirs.

Between 1968 and 1973 The Janes provided an estimated 11,000 safe, affordable, illegal abortions to those who found them. And they did this largely without the help of licensed doctors, save for receiving early assistance from civil rights leader Dr. Theodore R.M. Howard.

That means they learned how to safely perform abortions themselves, but only after they found out that the highly skillful man who treated their clients well and went by the codename Dr. Kaplan was, in reality, not a doctor. He was a tuckpointing specialist with a raspy laugh named Mike.

By the time directors, Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes reveal that The Janes didn't know their abortion specialist was only licensed to work on bricks and mortar, however, the viewer is long past being disturbed by such news. Mike didn't harass their clients and he did his job cleanly and well. None of the women who came to The Janes died because of receiving a procedure from them.

"If you start worrying about all the little details, you won't get anything done."

They ran their network like a spy ring and were so fiercely devoted to maintaining their clients' privacy that as they were being carted off to jail, they began eating the cards their identifying information was printed on. ("I don't know if you've ever tried to eat an index card, but it . . . it's very fibrous," one quips.)

There's a specificity to "The Janes" that is partly attributable to Pildes' connection to the story. Her brother Daniel Arcana is a producer and the son of Judith Arcana, one of the film's featured subjects. That lends an intimacy and trust to the film that glosses over the very narrow scope of its testimonials, making it difficult to ignore the whiteness of its perspective in the film's first half.

Part of this is a structural issue; only when about 50 minutes have passed do the participating Janes bring up that the women running the network were primarily white, which they recognized was a blind spot. As the Janes' reach expanded and another organization, the Clergy Consultation Service, stepped in to serve women with the economic means to travel to places where abortion was legal, the Janes mainly served the poor and women of color from Chicago's South and West sides.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Yet we don't see many non-white women in "The Janes," save for recurring testimony from Marie Leaner, one of its Black members, and a woman named Crystal O., providing her account of accompanying a friend to get an abortion at the age of 14.

Such gaps may be somewhat excusable in a story designed to be this tightly focused. At the same time, anyone who knows Theodore R.M. Howard's role in Chicago history and his view that safe, legal abortion is part of civil rights activism may wonder why none of the subjects in the film was invited to connect those dots for the audience.

Noticing this requires knowing that history, and maybe some of them did. Of course, the counterpoint is that the limited scope of "The Janes" is the point, along with its casual presentation. They were one group in one large city, but they represent a will that's present in towns across the United States. Far fewer obstacles were aligned against them back then too.

Overturning Roe v. Wade is expected to guarantee that roughly half of the country's population residing in at least 20 states would no longer have access to safe, legal abortions. Today's "Janes" equivalents have a draconian partisan apparatus aligned against them that could result in charges as serious as murder. But those activists may take some heart in Oliver's casual bravery regarding The Janes' work: "If you start worrying about all the little details, you won't get anything done."

"The Janes" premieres Wednesday, June 8 at 9 p.m. on HBO and streams on HBO Max. Watch a trailer for it below, via YouTube.

More stories like this: