The kitchen has become associated with routine and ritual, of domestic practices and gendered activities, but it is also the site of a gradual shift toward the ‘democratisation’ of domesticity

Opinion: Looking back over the past few years, the pandemic called into question many things about the way we live. The shift to working from home, which is likely to stay well after Covid has waned, will drive the need for more flexible and adaptable spaces, and to acknowledge the cultural changes will redefine how we live, including those that led to the kitchen doubling as a home office.

As part of my PhD by creative practice, I am looking at the history of domestic spaces of a group of women who lived in and commissioned modernist homes in Titirangi, west Auckland. This research, as well as the pandemic, has prompted me to think about the recent history of the kitchen, how it has reflected and made visible the inter-relational nature of domesticity, of gender, femininity and masculinity, here and internationally.

READ MORE:

* Flatpack homes: a sustainable future for emergency housing

* Housing crisis: Fresh blows from Gabrielle

* Let’s end obsession with building poor housing as cheaply as possible

The kitchen has long been a site in which gendered roles and responsibilities are experienced and sometimes contested. It is a space that has become associated with routine and ritual, of domestic practices and often highly gendered activities, but also the site of a gradual shift toward the ‘democratisation’ of domesticity with significantly greater equality between men and women.

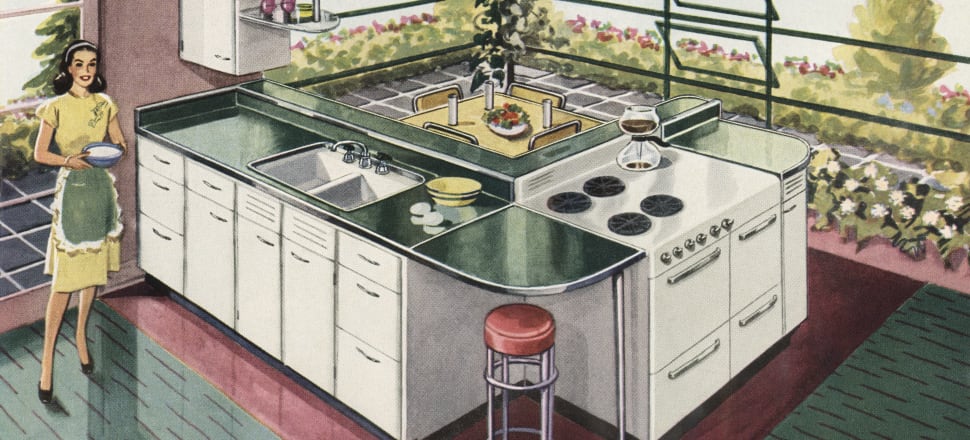

The 1950s celebrated modernism as an architectural style that would give way to more open designs, greater fluidity between the kitchen, eating and leisure spaces

To put the kitchen in architectural and design context, we can look back to the Bauhaus in the 1920s, in Dessau in Germany, which began to investigate the boundaries between private and public interior spaces, and how these encroached on each other. This was a period of worldwide industrial production and efficiencies that focused on getting people moving, which included helping women move around the kitchen more easily, to streamline kitchen labour.

Bauhaus’s early kitchen designs sought to incorporate the idea of sleek, continuous countertops as the standard for a modern kitchen as a response to designs that articulated the more mobile age, in both form and function.

In the 1940s in America, the concept of the triangle or the golden triangle in the kitchen began to take hold, which can still be seen in contemporary kitchens of today. The triangle was based on industrial motion studies in the 1940s aimed at increased efficiency. Frederick Taylor, an American mechanical engineer who went on to become an influential consultant on improving industrial efficiency, and the principles he applied to the factory began to be applied to the kitchen.

The three key kitchen items – sink, fridge, and stove were spaced equilaterally apart so the cook could simply pivot from place to place as she (and the person in the kitchen was then almost always female) moved through food prep, cooking and clearing up.

The 1950s celebrated modernism as an architectural style that would give way to more open designs, greater fluidity between the kitchen, eating and leisure spaces. This was the beginning of the aestheticisation of kitchen interiors, with cabinetry painted in ‘ice cream-flavoured’ pastel shades and Formica counter tops and tables.

However, opening up kitchens to the rest of the home put housework and women on display, and increased the pressure on them to achieve and maintain particular standards – of dress, of efficiency, of calm composure in the heat of the kitchen. (Perhaps it wasn’t coincidental this was a time when increasing numbers of women were prescribed Valium, in the US and New Zealand.)

Modern food production introduced frozen foods, condensed soups, and canned and packaged foods making some aspects of homemaking easier for women to get dinner ready. There were Betty Crocker cakes, which required adding a fresh egg to a packet of cake mixture, to produce a cake that looked (and presumably tasted) like the real thing, as if had been made from scratch.

In the summer of 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon travelled to Moscow to formally open the American National Exhibit at Sokolniki Park in Moscow under a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev accompanied Nixon on a tour of the exhibit, with a team of journalists and photographers trailing them. An entire house was built for the exhibition which the American exhibitors claimed that anyone in the US could afford. This was a provocative politicisation of the kitchen which was on display filled with labour-saving and recreational devices such as a fridge, a kettle and an InSinkErator waste disposer, to represent the fruits of the capitalist American consumer market.

Over the following years the second wave of feminism takes hold from the US, a shift in what were considered women’s ‘responsibilities’ and the concept of the female consumer and her purchasing power became more potent.

We need to feel connected to the materials used, honest materials such as timber, ceramics and glass, materials that can be pre-loved and recycled, and unlikely to end up in landfill

Until the 1950s the kitchen was seen as a utilitarian space, but with the changing social norms and feminism, the kitchen was bought out of the shadows, and began to gain equal aesthetic importance to the rest of the interiors.

Then came television, and televised cooking shows, which took kitchens into living rooms, as a form of theatre that could be viewed from the comfort of our couch. We’ve had the Julia Childs of our age, and in New Zealand, Hudson and Halls and Graeme Kerr, the galloping gourmets of the early 1970s.

The competitive approach of many programmes in the past couple of decades presents food preparation as ‘sport’, with chefs as competitors or coaches rather than cooks as in MasterChef. Viewed in this light, the kitchen is no longer a women’s ‘homely’, feminised domestic space, but becomes a stadium where culinary competitions are staged, using specialised knives, gadgets and tools serving as equipment to aid performance.

There was a drive in New Zealand to design kitchens for multiple users and purposes long before the pandemic required many families to use them as offices. We now live in a society where the nuclear family is no longer the assumed norm, and blended families, solo-parent families and same-sex marriages are replacing the traditional family dynamic. Māori and Pacifika communities, as well as Asian and Indian communities, all have specific traditions and practice the concept of zones in their inter-generational multi-user use of the kitchen.

The home houses memory and traditions of our daily routines, where we begin and end our day. The kitchen once was placed at the rear of the house, out of public view, where gendered labour was concealed. The kitchen has long been a symbol of domesticity where women were often marginalised, but shifting gender roles have now transformed the kitchen, as I see it, into a place of collective activity, of connection and conversation, the site of everyday life-capturing memories.

The kitchen is likely to continue to evolve, and shift in shape and use. What, for instance, would a genuinely sustainable kitchen look like? At the very least, it would have cabinetry that lasts for a long period of time, for several decades rather than one that needs to be ‘redone’ every 10 years, incorporating authenticity and aesthetics. We need to feel connected to the materials used, honest materials such as timber, ceramics and glass, materials that can be pre-loved and recycled, and unlikely to end up in landfill.

It will also involve thinking about the integrity of our food, where it comes from, as well as reducing what ends up in the bin. But whatever form it assumes, the kitchen is likely to be the heart of any home, a space that needs to be considered, and never taken for granted.

This was part of a talk that Gina Hochstein gave as co-chair for Architecture + Women, New Zealand for Blum in April 2023, on the topic of the Evolution of the kitchen over the past 100 years.