On a cool, sunny day in February — typical weather for this time in India’s Gangetic plains — loud chants of ‘Har Har Mahadev’ ring through the air inside the heavily guarded Kashi Vishwanath temple in Uttar Pradesh’s Varanasi, one of the oldest living cities in the world. Devotees try to weave their way in. There is another line of pilgrims, who have purchased a ticket worth ₹300 each to get a sugam darshan (comfortable view) of the deity, Shiva. Each of them is first frisked by security personnel before being let in.

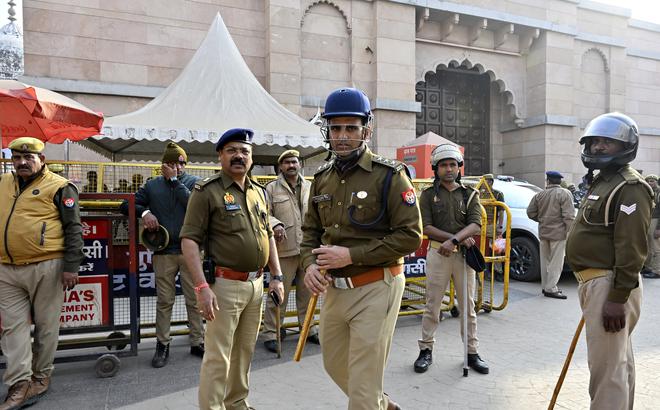

Outside, there is tension in the air. Harassed-looking policemen form a human barricade. Hundreds of Muslims have just finished the Friday prayers in Gyanvapi mosque, which sits next to the temple.

“Jaldi aage badho (walk fast),” says a policeman to a group of Muslim boys who stop at a shop outside the temple where some Hindu boys are chanting ‘Jai Shree Ram’. “Nara mat lagao (don’t raise slogans),” he says firmly.

A disputed spot

The gigantic three-domed Gyanvapi mosque, constructed by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1669, has been standing next to the gold-plated Kashi Vishwanath temple, built by Maratha queen Ahilyabai Holkar in 1780, for centuries. However, the mosque has now become a bone of contention between Hindus and Muslims in Varanasi, the parliamentary constituency of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The Hindus say that an ancient Adi Vishweshwar (Shiva) temple was demolished by Aurangzeb and lies beneath the mosque. They want it back. The Muslims wish to retain their prayer space. Their claim to possession is the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which prohibits the conversion of any place of worship and provides for the maintenance of the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947, the day of Independence.

The dispute was moved to court in 1991. It intensified in July 2023 when a local court ordered a survey of the Gyanvapi mosque by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to ascertain whether it was “constructed over a pre-existing structure of a Hindu temple”. Weeks later, the ASI submitted its report, concluding that a Hindu temple did exist before the construction of the mosque. On January 31, the local court ordered the district administration to perform a puja, raag, bhog (worship the deity, offer food, and bathe it) in the southern cellar of the Gyanvapi mosque.

District Magistrate S. Rajalingam acted swiftly on the court order, delivered by judge A.K. Vishvesha on the day of his retirement. He went inside the mosque the same day, instructed that the iron fence and barricades be removed, and placed idols at the spot. The puja was performed by a priest, who was selected by the Kashi Vishwanath temple trust.

Angry over the sudden turn of events, Muslims knocked on the doors of the Allahabad High Court to stop the puja. Hindus have been told that pujas can be conducted by a priest only in the cellar as long as the matter is sub-judice.

A tense town

Santosh Kumar, 37, sells paan (betel leaves) near the Godaulia Chowk, which leads to the temple. The area is chock-o-block with pedestrians, rickshaws, shanties, and shops selling cloth, souvenirs, and hot food. There is a police picket every 200-300 meters on this busy stretch. “It is our temple, so we must get it. If some sacrifices are required, we are ready for it,” he says.

Forty-year-old Amit Seth’s land was acquired for the Kashi-Vishwanath corridor. Though he was paid a heafty compensation, he says that the “mandir-masjid fight” is political and has nothing to do with the “common people’s faith”.

Anand, who sells flowers outside the temple, stares at the mammoth metal door at the entrance of the corridor. He rues that it is only opened when Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath visit the temple. “Bana janata ke paise se hai, magar janta ke liye nahi khulta ye darwaza (The door is made from public money, but it is never opened for the public),” he says.

As the sun sets, the crowd swells at the Godaulia Chowk. Pragya Pathak, Deputy Superintendent of Police, along with around 30 personnel, begins a flag march in the adjacent lanes, which have a significant Muslim population. She says the flag march is a routine drill as “festivals are approaching”.

Mohammad Azaher, 43, a resident, disagrees. “The police are trying to provoke us by conducting these flag marches. It is not required. We have already given up,” he says.

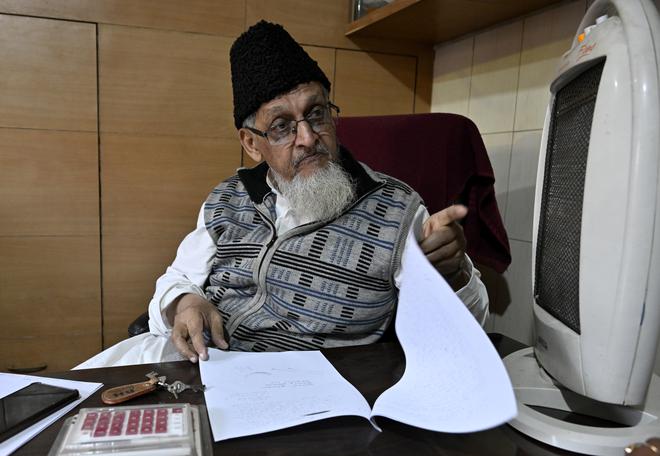

S.M. Yasin, joint secretary of the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee, which manages the Gyanvapi mosque, believes that the Central and State governments are involved in the dispute. “An ASI survey was conducted inside the mosque. A puja was conducted inside the mosque. Tomorrow someone may even want to demolish the mosque. A Muslim can only watch while this grave injustice plays out,” he says, adding that he has lost faith in the judiciary.

Yasin wonders why the District Magistrate deemed it so urgent to comply with the court order. “If the administration is so serious about ensuring compliance with court orders, why haven’t they opened the Noori Masjid even after the directions of the Supreme Court,” he asks.

Located 4 kilometres from the Gyanvapi mosque in the Madanpur area, Noori Masjid is a defaced double storey structure which has been closed for decades. A Shiva temple, the Tilbhandeshwar, is situated 200m away from it.

“The administration disallows prayers in this mosque citing law and order,” says Mohiuddin, who had donated his house to the Waqf Board, a legal body that ensures the proper administration of Waqf, or property donated in the name of god for religious and charitable purposes. His house was later converted into the mosque.

“It was the last wish of my wife Zahida Bibi that our house be converted into a mosque. I won’t be able to die in peace as I have failed to fulfil her last wish,” he says, waving the Supreme Court order of 2009, delivered by Justice Markandey Katju, which paved the way for prayers in this mosque.

Residents in the area, who are predominantly Muslim, say that prayers are still not allowed in the mosque despite multiple requests.

Editorial | Legitimising revanchism: On the Gyanvapi case and the Allahabad High Court

District Magistrate Rajalingam says he is aware of the issue, but refuses to comment on why it remains locked up.

Muslims in the city are also unhappy that videos of the puja being performed inside the southern cellar of the Gyanvapi mosque are making the rounds on social media. They believe it is being done to “humiliate” the community.

“The court has said a puja can be performed, but it did not say circulate videos of it to provoke sentiments,” says Yasin. Moreover, he says, it is strange that these videos are being circulated when phones are not allowed inside the temple. He alleges that the administration circulated the videos. He also wonders why devotees are allowed to perform darshan in the cellar, as this was not in the court order.

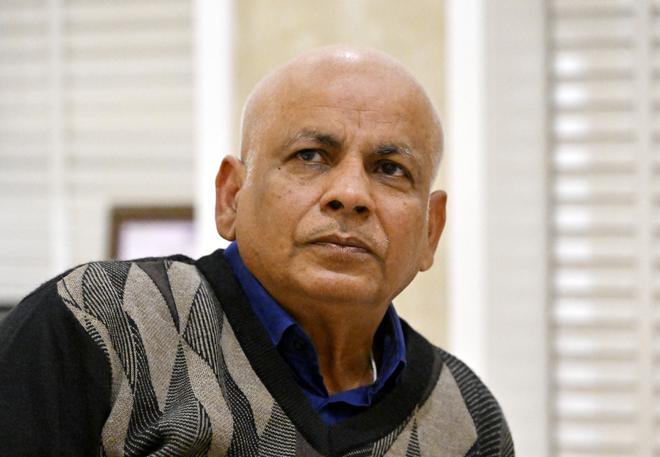

Refuting Yasin’s allegations, the Chief Executive Officer of the Kashi Vishwanath temple trust and vice-president of Uttar Pradesh Provincial Civil Services Officers Association, Vishwa Bhushan Mishra, says that the administration has not recorded any videos of the puja. “We allowed the pilgrims to have a glimpse of the cellar because there was high demand. Each of them was requesting this. We allowed darshan from a distance, which neither disturbs the management of the temple nor creates a law-and-order issue,” he says.

The changing character of a city

Vishwambar Nath Mishra is the Mahant or the religious head of Varanasi’s second-most visited temple, the Sankat Mochan, which is believed by devotees to have been built by the poet and saint Goswami Tulsidas in the 16th century. The temple is dedicated to Hanuman, a devoted companion of Lord Rama. “Hundreds of ancient temples and mosques have quietly witnessed the transformation of Varanasi over the years,” says Mishra. “This dispute is taking away from the city’s history of peaceful co-existence.”

Mishra believes that Varanasi represents a model of India where all religions and communities live together in peace. “Whatever happened is now in the past. It was accepted by the people, and everyone lived amicably,” he says.

Terming the structural and social changes happening in Varanasi as “part of politics,” Mishra says they are killing the “soul” of the city.

“Have you seen that giant Kashi Vishwanath corridor built with the red sandstone? Does it match the aesthetics of this city which is famous for its ancient architecture, narrow lanes, spirituality, and harmony? First, they change the face of the town and now they want to keep communities divided,” he says, alleging that those fighting the Gyanvapi case are “outsiders”.

Lacour Sophie, from Paris, is visiting Varanasi for the second time. She feels there is something missing in the city now. “The narrow lanes near the temple are gone. The ghats look cleaner, but the spirituality is missing. There are more tourists here than pilgrims,” she says.

Others disagree and believe that development is important. Tribhuvan Nath, 76, from the Kabirdham district of Chhattisgarh, is staying at Mukti Bhawan, a hostel run by a trust. Here, ailing people check in with the belief that they will attain salvation if they die in Varanasi. Tribhuvan has come with his older brother Nirgun Nath, who suffers from a liver problem.

“My father and mother died in Varanasi. Nirgun will be the fifth person in my family to die here. I have seen this city changing for the good. Earlier, travelling to Varanasi was difficult. Now, the roads are good and so is transport. Even the power supply is uninterrupted,” says Tribhuvan.

Nitin and Jagriti Jain, a couple from Ahmedabad, feel that the city has transformed exactly the way it should. “Spirituality and development can go hand in hand. For how long can people keep coming to crowded and narrow lanes with poor accommodation? The Prime Minister’s vision is visible in the development of this city,” says Jagriti, after giving a sound bite to a television channel praising the court’s order of allowing puja inside the Gyanvapi mosque.

Demands and despair

Manish Chandra, who works at a hotel near the temple, says, “Soon after the court order, people began cancelling their bookings in our hotel. They said that they are afraid of travelling to Varanasi as they think that the city is on the verge of riots”.

Rajendra Kumar, who owns a saree shop at the city’s Maidagin area, says his Muslim workers are fearful. This affects him as the rich Banarasi silk sarees are mostly woven by Muslims, whereas shopkeepers and clients are mostly Hindu.

Firoza Bano, who helps her husband Mumtaz Ahmed in dyeing the silk thread on the veranda of their small dimly lit house in the Reori Talab area, feels that Muslims should hand over the mosque to the Hindus. She asks, “What we will do with the mosque if the future of our children is destroyed?”

Earlier this week, in the State Assembly, Chief Minister Adityanath made a pitch to reclaim the religious sites of Kashi and Mathura where the disputed Gyanvapi and Shahi Idgah mosques are situated. “In the Mahabharata, Krishna asked Duryodhana for five villages for the Pandavas... Hindus are only asking for three shrines, that is, Ayodhya, Kashi, and Mathura,” he said.

The situation worries Yasin. “How many mosques will satisfy the Hindus,” he asks. He recalls the slogan coined by right-wing groups during the demolition of the Babri Masjid by Hindutva proponents. It went, ‘Ayodhya to sirf jhanki hai, abhi Kashi, Mathura baki hai (Ayodhya is only the trailer, now Kashi and Mathura remain).’

“They have a new slogan now,” he says quietly. “It goes, ‘Teen nahi tees hazaar, ab na rahegi koi masjid ya mazaar (Not three but 30,000; now there will be no mosque or tomb).’”