Human sexuality has long been a subject of fascination and curiosity in the scientific community. Researchers from different fields have sought to understand why we are attracted to certain people and how our sexual orientation develops.

From Sigmund Freud to Judith Butler, the road to a science of sexuality is a fascinating history of ambition and culture wars, error and scientific breakthrough.

My recent research continues the quest to make a science out of sexuality. Two opposing schools of thought currently divide the field: psychoanalysis and queer theory.

Psychoanalysts believe desire follows specific laws and follows predictable patterns, while queer theorists argue that laws have exceptions and advocate for a more creative view of sexuality.

My research proposes an information theory of desire that straddles the line these two groups by arguing we should consider the object of our desire as information.

Psychoanalysis can help us understand how this particular kind of information is stored, while queer theory can help us understand how this information is organized and re-organized internally.

Birth of psychoanalysis

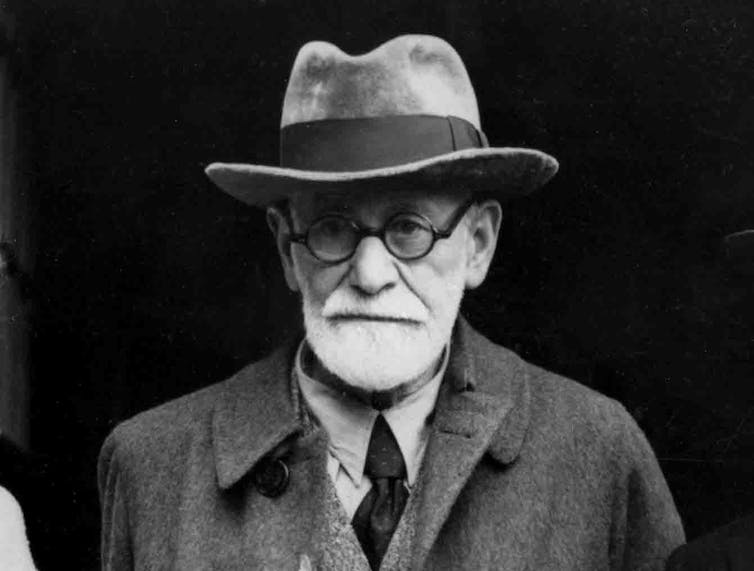

Sigmund Freud, originally trained as a physician, believed in the scientific basis of sexuality. He was the first to regard sex as the subject of a serious discussion. Starting in 1902, colleagues gathered every Wednesday in his apartment to discuss the psychoanalytic practice he established.

Debates about how to study sexuality soon divided Freud’s circle of colleagues. In 1911, Alfred Adler broke away and turned psychoanalysis into social and cultural studies. Two years later, Carl Jung broke away and turned toward philosophical and existential questions.

At the time, Lou Andreas-Salomé, the first female psychoanalyst, did not believe either separation threatened the scientific status of psychoanalysis:

“The source of its vitality does not lie in any hazy mixture of science and sectarianism, but in having adopted as a fundamental principle that which is the highest principle of all scientific activity. I mean honesty.”

Though Freud retained Andreas-Salomé’s loyalty until the end, he didn’t share her optimism about the uniting power of honesty and thought divisions at the heart of his movement would delegitimize it.

North American psychology

The quest to turn sexuality into a credible science survived Freud, especially in North America. Clinically trained psychologists in the post-Second World War era borrowed Freudian theories and employed traditional scientific methods to empirically test them.

Dismissing Freud’s exclusive interest in individual case studies, American and Canadian psychologists aimed to understand populations more widely. However, this shift led to seeing homosexuals as a separate social group, which ultimately gave rise to homophobia and conversion therapy.

In the United Kingdom, Freud’s daughter Anna promoted curing homosexuality even though her father had denounced similar practices.

In France, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan urged his colleagues to return to Freud’s methods. Consumer culture silenced similar voices in North America.

Psychotherapy lost its scientific motto — the pursuit of truth — and became a matter of pursuing happiness. Keenly aware how the big screen dumbed down Freud’s psychology, Marilyn Monroe — a serious reader of psychoanalysis — turned down starring in a movie about him out of respect.

Sexuality nowadays

By the time Canada decriminalized homosexuality in 1969 — and the American Psychological Association unclassified it as a mental disorder four years later — sexuality studies had shied away from its psychological origins.

But biological explanations prevailed. Scientists wondered whether homosexuality ran in the family and hypothesized the existence of a gay gene and its relationship to natural selection.

Despite the politically correct turn away from “why gay?” to “how gay?” in post–1970s clinical research, and the anti-psychological turn in feminism known as the Freud Wars of the 1980s, the prospect of a science of sexuality almost vanished until queer theorists made its case again in the 1990s.

Queer theory rejected fixed collective identities and re-emphasized individual case studies the same way Freud had. Instead, queer theorists viewed sexuality as something more dynamic.

Queer theorists like Judith Butler emphasized the relationship between internal and external life. They highlighted how drag artists disrupt the way we assign gender on a daily basis.

This disconnect between what we see and the meaning we give it is a chance for sexuality to break with habit and become unpredictable.

The challenge of our current moment

Nowadays, many regard sexuality as too complicated or too subjective to become a science. Freud’s theories are often dismissed as pseudoscience.

But this outlook is dangerous to the pursuit of science. According to Elizabeth Young–Bruehl, a queer psychoanalyst who practised in Toronto until her death in 2009, we have abandoned Freud’s depth psychology and his theory of the unconscious and promoted instead superficial psychological theories.

Homophobia and caricatures of psychoanalysis originated with our relationship to science, not Freud’s. Though he was keen on establishing a science of sexuality, he regarded that science as historical rather than experimental.

Historical sciences aim to reconstruct past events and favour the uniqueness of detail and individual cases. Experimental sciences, on the other hand, are concerned with the future and whether an event will repeat itself.

Information theory of desire

Why do individuals come out as gay or bisexual at a particular point in their lives, but not earlier? Why do some first same-sex experiences shape a queer identity while others do not?

An information theory of desire might offer insights into these questions. When queer people talk about the defining moment when they came out to themselves, it can be useful to think of self-acceptance as a kind of computing command — an input that demands a radical re-organization of someone’s information network or identity.

Life events become inputs, and sexual orientations and gender identities become information networks. Certain same-sex experiences may only result in partial changes to the information network, while others may lead to the complete re-configuring of someone’s identity.

What can we discover with a science of sexuality? Freud’s loyal friend Andreas-Salomé was right to regard honesty as the highest principle of any scientific activity. Without it, we would be dealing with incorrect inputs or information networks viewed upside down.

Pride Month is not just a celebration of sexuality — it’s also a celebration of science.

Rayyan Dabbous does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.