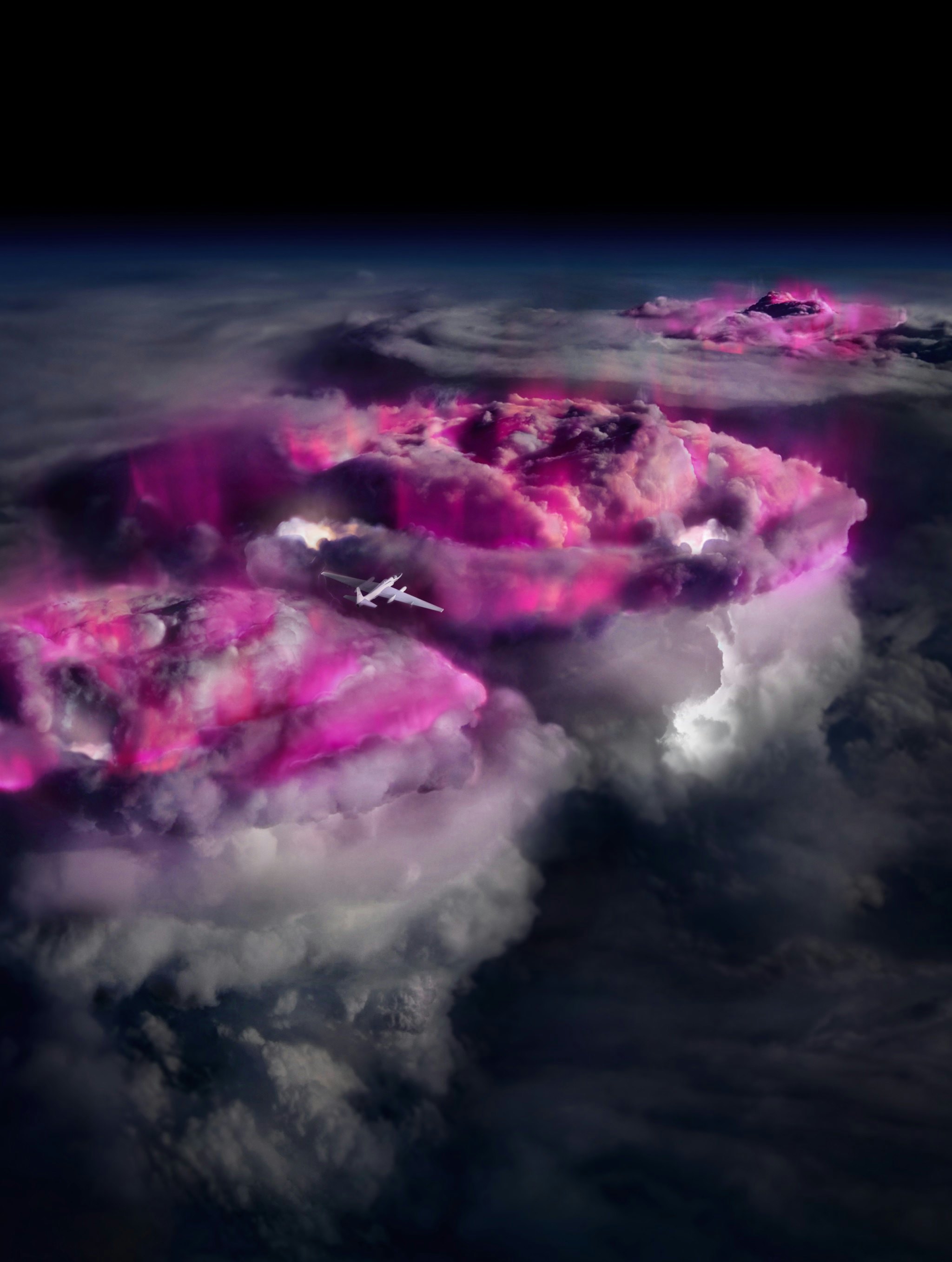

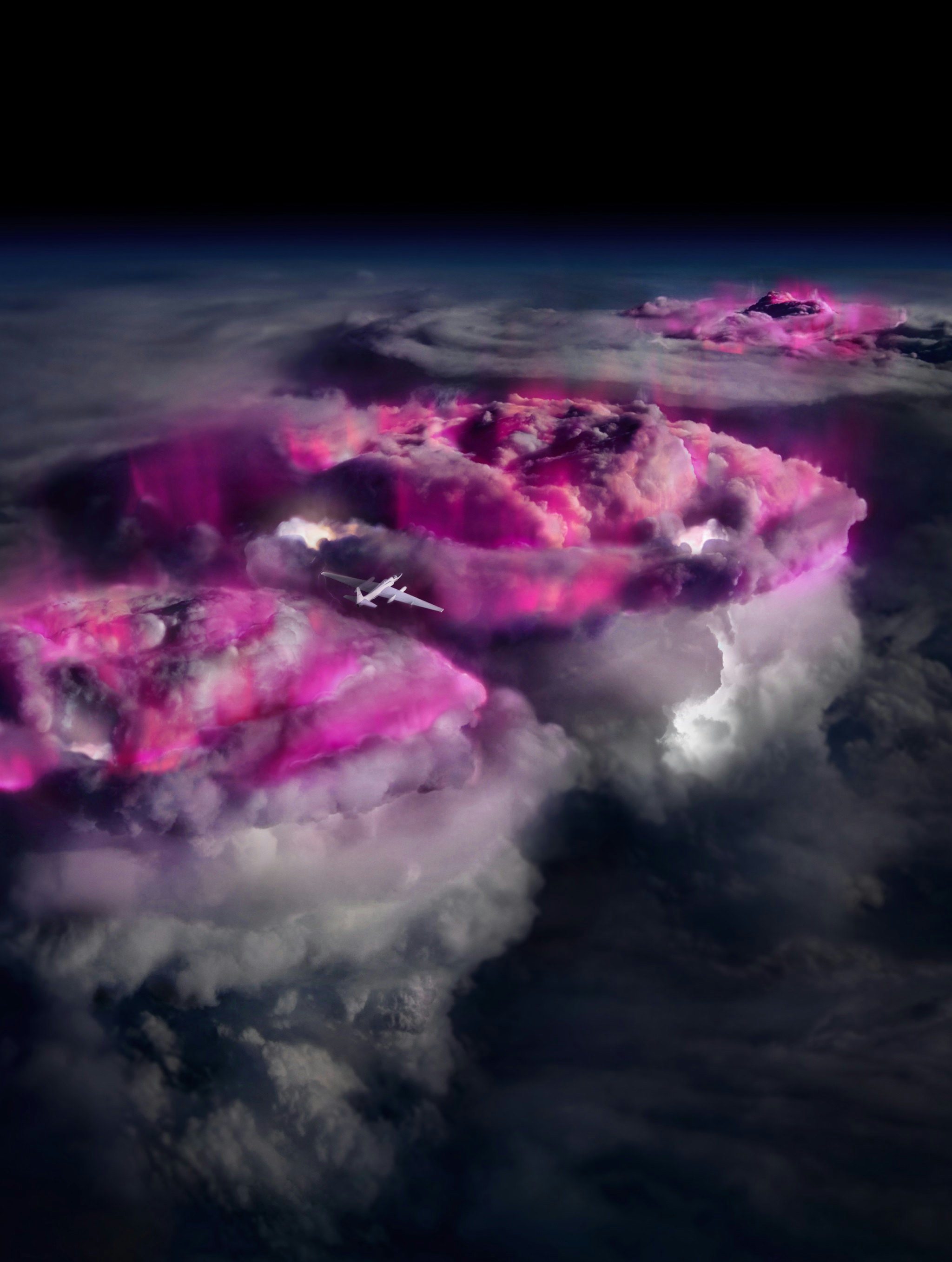

NASA sent a retired Cold War spy plane on a storm-chasing mission, and it discovered that big thunderstorms are very radioactive.

Large thunderstorms produce so much gamma radiation that the clouds are actually glowing with it, according to a recent study, which used NASA’s ER-2 research plane to study gamma rays in tropical thunderstorms. University of Bergen space physicist Nikolai Østgaard and his colleagues published their findings in the journal Nature.

Thunderstorms are Radioactive

NASA’s retired Cold War spy plane, cruising just over the towering cloud tops of massive thunderstorms over the Caribbean and Central America, spotted storm clouds glowing with gamma rays. Instruments aboard the plane recorded bright, quick bursts of gamma rays whenever lightning flashed through the clouds, but also a constant flickering glow of high-energy radiation in the clouds between flashes — and two previously unseen kinds of short gamma ray bursts.

Out of 10 thunderstorms the aircraft flew over, 9 of them were alight with gamma rays, suggesting that large thunderstorms churn up gamma rays shockingly often.

The results could shed some light on exactly how lightning forms — a process whose details meteorologists still don't fully understand.

"I think everyone assumes that we figured out lightning a long time ago, but it's an over looked area," University of New Hampshire physicist Joseph Dwyer, who wasn't involved in the recent study, said in a press release.

Storm Chasing in a Spy Plane

In the 1990s, gamma rays from a few large thunderstorms pinged the sensors on NASA satellites, which had been built to study gamma ray bursts coming from dead stars colliding millions of light years away. But those satellites’ instruments weren’t designed to study radiation coming from the planet right below them, so the flashes of gamma rays coming from thunderstorms — dubbed Terrestrial Gamma-ray Flashes — remained a puzzling bit of trivia.

The U2 spyplane, on the other hand, was built specifically to study things happening just below its 70,000-foot cruising altitude. After the Cold War thawed, NASA got its hands on a pair of them and refitted the planes to do science instead of spy craft. NASA’s ER-2s, as they’re now called, have helped scientists study the upper atmosphere and test instruments for future satellites. Most recently, one of them flew over the ten-mile-high tops of some massive thunderstorms over the Caribbean and Central America, carrying instruments that measured gamma rays.

“We can fly directly over the cloud top, as close as possible to the gamma-ray source,” says Østgaard in a recent statement. Østgaard and his colleagues recorded 130 terrestrial gamma-ray flashes during the recent flights.

From that data, the researchers discovered that large thunderstorms release gamma rays much more often than anyone realized. Storms generate incredibly strong electrical fields, and those electrical fields act like giant particle accelerators, shooting electrons through the sky at tremendous speeds. When one of those speeding electrons inevitably slams into an air molecule (the sky is full of them), that collision releases a burst of energy and scatters subatomic particles, also moving at high speed, in a bunch of other directions. The energy of each collision increases until eventually, the energy releases gamma rays.

They discovered that the largest thunderstorms produce gamma rays a lot more often than we thought, partly because their strong electrical fields act like particle accelerators and fling electrons through the sky at tremendous speeds; that is, until those speeding electrons crash into an air molecule. The collision releases a burst of energy and scatters subatomic particles, also moving at tremendous speeds, leading to more collisions and more bursts of energy. Eventually, the collisions happen with enough energy to create small nuclear reactions, which release bursts of gamma rays — and even produce some short-lived antimatter.

“As it turns out, essentially all big thunderstorms generate gamma rays all day long in many different forms,” says Duke University researcher Steven Cummer, a coauthor of the study, in a recent statement.

The Unfriendly Skies?

The nuclear reactions produced by speeding electrons colliding with air molecules in thunderstorms are much, much smaller than a nuclear bomb; please do not panic. The radiation they release doesn’t mean that nearby aircraft, or their passengers, are in danger — at least not from radiation. Flying through big storms is a bad idea for more obvious reasons.

“Even knowing what we now know, I don’t worry about flying any more than I used to,” says Cummer. “The radiation would be the least of your problems if you found yourself there. Airplanes avoid flying in active thunderstorm cores due to the extreme turbulence and winds.”

Eerie Gamma-Ray Glow

Lightning flashes aren’t just happening in visible light. Most of the terrestrial gamma-ray flashes NASA’s spy plane measured happened alongside big flashes of lightning, and they last just millionths of a second. Østgaard and his colleagues suggest that when lightning discharges, it gives an extra boost of energy to those already super-energized electrons zipping around the storm cloud, so their collisions can trigger the nuclear reactions that release gamma rays.

But the tops of the biggest, most violent storms are also constantly alight with a flickering, baleful gamma ray glow. Østgaard and his colleagues compare the clouds simmering with gamma rays to a pot of water at a low boil. The glow can last for minutes at a time, and the constant release of energy may prevent the storm from building up to even more dramatic gamma ray bursts.

The spy plane’s instruments also recorded two previously unknown types of gamma ray flashes in the clouds: very short, bright bursts of radiation that didn’t coincide with lightning. One of them is a series of short flashes, blinking in a rapid sequence that lasts about a tenth of a second. Østgaard and his colleagues dubbed these “flickering gamma-ray flashes.”

“They’re almost impossible to detect from space,” said University of Bergen space physicist Martino Marisaldi, a coauthor of the study, in a recent statement. “But when you are flying at12.5 miles high, you're so close that you will see them.”

The other new discovery is an extremely quick burst of gamma rays, released in just a thousandth of a second.

“Those two new forms of gamma radiation are what I find most interesting,” Cummer said. “They don’t seem to be associated with developing lightning flashes. They emerge spontaneously somehow. There are hints in the data that they may actually be linked to the processes that initiate lightning flashes, which are still a mystery to scientists.”