Tennis loves using quick adjectives to characterize players—graceful Roger Federer and gritty Rafael Nadal and precise Novak Djokovic. For years, the Dutch player Robin Haase could not be discussed without the accompanying descriptor dangerous. Since turning pro in 2005 at age 17, Haase was known for his bursts of excellence, eyebrow-raising shotmaking, and unanswerable power that came from torquing his greyhound-slender physique—6'3", 170 pounds—and letting loose with one of the sport’s liveliest arms.

Danger, though, can be averted and overcome and defused. And so often Haase would work in flourishes. He’d play spectacularly for an hour or so …. and then, in tennis terms, go off the boil. During his career, he’d taken sets off Federer and Nadal and battled mightily with Djokovic—but beaten none. Still, here was a player who would win his share of matches, snatch the odd title, thrive in doubles as well as singles, and make upwards of $1 million a year as a reliable ATP Tour cast member.

Haase entered 2016 with swollen hopes. He was 28, the meaty prime for a tennis player these days. After years of knee troubles, he was finally healthy. Maybe, he reckoned, this would be the year he would fully deploy his gifts and turn all that potential—that danger—into consistent results.

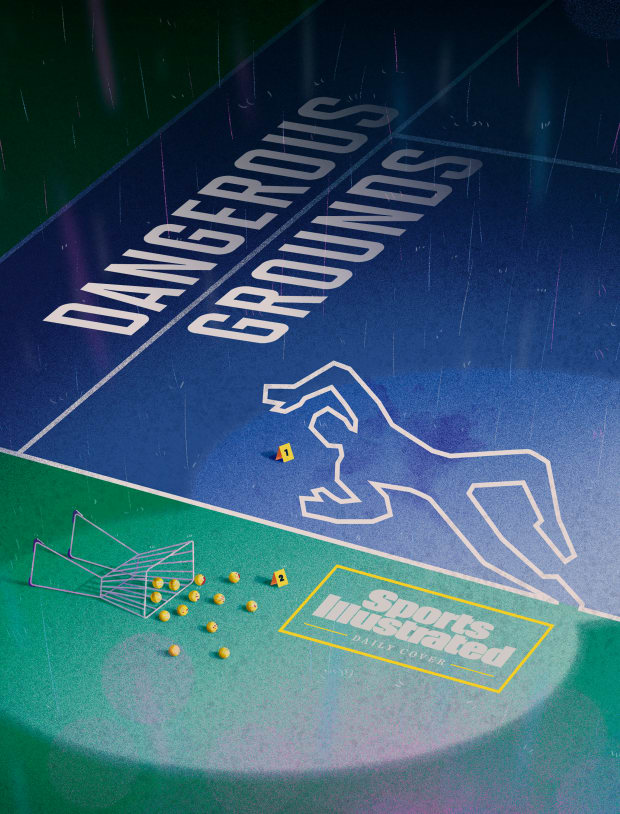

Illustration by Davide Barco

He started the season in Doha, winning a match and then falling to Nadal. No shame in that. He then won three matches in Auckland before losing to South Africa’s Kevin Anderson, once a top-five player. No shame in that, either. But then Haase struggled, losing early everywhere from the Australian Open to the Rotterdam event not far from his hometown, The Hague. His confidence was fissured. The return of those knee troubles wasn’t helping matters.

And then came an altogether different kind of blow. The first week of March 2016, as he prepared to head to the showcase event in Indian Wells, Calif., a tournament—here comes another of the sport’s shorthands—inevitably referred to as “tennis’ fifth major,” Haase received startling news. One of his close friends had been murdered.

Initially, the details were sketchy but brutal. On the night of March 3, Koen Everink—a running buddy not just of Haase’s, but of many in Dutch tennis circles—was stabbed in his home in Bilthoven, outside Amsterdam. The intruder had entered Everink’s home, taken a knife from the kitchen and plunged it into Everink’s body no fewer than 24 times, breaking the victim’s sternum and ribs in the process. In the morning, Everink’s 6-year-old daughter walked downstairs and discovered her father on the floor, lying alongside a knife, dead in a sea of blood.

With a day to go before his flight from Amsterdam to Indian Wells, Haase thought about staying home and attending Everink’s funeral. He remembered, though, that Everink had accompanied him to Indian Wells the previous year. Haase decided that he would play the event in Everink’s honor. Haase’s mother and sister would attend the funeral in his stead.

Haase’s coach, Mark de Jong, was shaken as well. He, too, was friends with Everink. So much so that earlier on the night of the attack, de Jong had been at Everink’s home, drinking and watching sports on television. Having already given a statement to police, de Jong figured that he would accompany Haase to Indian Wells, nine time zones and 5,500 miles from Amsterdam. de Jong told friends that perhaps the distance might help him process the murder of his friend.

In the California desert, Haase and de Jong commiserated and shared their grief over the chilling murder of their friend. Haase says he was deeply shaken, maybe even in a state of shock. The fact pattern was almost incomprehensibly tragic. A gentle man in his early 40s was murdered. … The life snuffed out of him … in his home … in a country with one of the world’s lowest murder rates … with his 6-year-old daughter sleeping upstairs?

For all its congenital nuttiness, tennis doesn’t often intersect with capital crimes. That week in Indian Wells, word of the murder rocketed around the player lounge and locker room. Some players recalled seeing Everink at tournaments, where he would accompany Dutch players and wear a credential that conferred him access to the sport’s backstages. A number of players as well as ATP staffers stopped to offer condolences to Haase, a popular veteran and past member of the ATP Players’ Council.

In Indian Wells, Haase won a match (against Diego Schwartzman, who would later enter the top 10). Then he lost a match (against Alexandr Dolgopolov, who is now retired and serving in the Ukrainian army). But Haase’s head was elsewhere. Contacted at the time by the Dutch publication, Quote magazine, and asked about the murder of his pal Everink, Haase said: “I have no words…I thought he had found his peace. I had no indication that he was being threatened or anything like that.”

Little did Haase know, Everink’s killer was at Indian Wells that week, sitting across from him at meals, courtside when he played, sleeping in the room next door.

Andy Astfalck/BSR Agency/Getty Images

Even into his early 40s, Koen Everink cut a contradictory figure, at once outgoing and introverted, both a socialite and a mystery man. He succeeded in business but had sold his internet travel company, reportedly for $15 million, and was vague about his next venture. He drove the right car and often was at the right party, yet could be self-effacing about his appearance, joking about his receding hairline or his desire to lose weight. He also had a curious way of finding trouble.

In the summer of 2012, Everink had attended Sensation, an electronic dance music festival held in Amsterdam’s Johan Cruyff Arena. He was sitting in a box that included Badr Hari, a prominent Dutch kickboxer. At one point, Hari became convinced that Everink had insulted his girlfriend at the time, Estelle Cruyff, niece of legendary Dutch soccer player (and stadium namesake), Johan Cruyff.

Everink denied saying anything unkind and suggested that there must have been a misunderstanding. But what ensued was no shouting match or even a knockabout. When Everink went to the restroom, Hari followed him. A 6'6", 250-pound combat sport champion, Hari lunged at Everink, punched him, took him to the ground and snapped his ankle as if it were a carrot.

Hari conceded that he could, at times, be overwhelmed by his violent impulses, erupting “[like a] storm, a hurricane, a disaster.” According to a Dutch media report, “Hari only handed himself into the authorities through fear of being arrested by a SWAT team.” He was arrested, tried and ended up spending 14 months in Dutch prison for various assault charges, including the attack on Everink. Hari also was ordered to pay Everink roughly $40,000 in damages.

Everink had hoped for a stiffer punishment. As a result of the attack, he spent years in excruciating pain, unable to work, unsure whether he would walk again. When the judgment against Hari was rendered, Everink received threats from Hari’s fans, often over social media, blaming him for disrupting the kickboxer’s career.

Single, wealthy and looking to reinvigorate his life, Everink found refuge in the Dutch tennis community. He had always liked the sport. He had played a bit. And after the accident, he was granted entry into the circle of Dutch touring pros. The arrangement—not an uncommon one in tennis—was never formalized but everyone knew the terms: Everink would travel the world and get to tournaments on his own dime. There, players would leave him guest passes.

On site, Everink would help when he could—taking rackets to stringers, helping book practice courts, picking up the tab for team dinners—happy for companionship and access. Describing it as “therapeutic” after his trauma from being assaulted by Hari, Everink was happy to be part of the subculture. If friends joked that he was a groupie, so be it.

Henk Seppen/BSR Agency/Getty Images

When he wasn’t coaching Robin Haase on the ATP Tour, Mark de Jong was known as an inveterate poker player—and not a good one, playing without any discernible strategy. The Dutch version of PokerStars would later reveal data indicating that de Jong had lost $62,839 over the course of 72,900 hands, mostly at $0.25 or $0.50 per hand, a startling rate of loss. And it wasn’t just online. While at tennis events worldwide, de Jong would often head off to local casinos.

In 2015, de Jong came to Everink to ask about a loan to pay off his losses. Everink obliged but asked to be repaid as soon as possible. Everink reportedly threatened to go public about de Jong’s poker habit if he failed to fulfill the loan agreement.

The morning after the murder, de Jong, the last man known to see Everink alive, was questioned by police. During the investigation de Jong, then 27, claimed that after he left Everink’s home on the night of March 3, he was stopped by a group of three unknown men. He said that they entered his car and forced him to drive back to Everink’s home. Two of the men went into the home, while one remained in the car with de Jong. After a few minutes, the two men returned, and the foursome drove away. Eventually the three strangers got out, de Jong said, leaving him to drive home alone.

After providing this testimony, de Jong was released and flew to California. But in the weeks after the murder, with de Jong in the United States, the police investigation uncovered a trove of evidence against him. A knife found next to Everink’s body contained traces of DNA that matched de Jong’s. Police also found traces of blood in de Jong’s car. A search of de Jong’s iPad revealed a lengthy list of violent search terms that included “stab in the neck,” “stab in the back,” “death by strangulation,” “carotid artery” and “knock on the back of the head.”

After his run in Indian Wells, Haase, accompanied by de Jong, went to the Miami Open in Key Biscayne, Fla. Hobbled by a bone bruise, Haase withdrew before his first match. He and his coach boarded a KLM flight back to Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. Haase was upgraded to business class; de Jong flew in coach.

When the overnight flight landed at 6 a.m., and Haase arrived at baggage claim, a Dutch detective asked him to come into a small room. There, the detective explained that his coach had been arrested as he’d gotten off the flight. Haase figured he’d just been summoned for more questioning. Then it hit him.

“Wait, do you mean taken for questioning? Or, like, arrested?”

Haase was told that, yes, Mark de Jong had been taken into custody. He was suspected of murdering Koen Everink.

For all the variables that can disrupt an athletic career, coach charged with friend’s murder is not particularly common. Now, in addition to dealing with the gruesome death of Everink, Haase’s trauma was compounded by the implication of his coach.

Word of de Jong’s arrest spread quickly in the Netherlands. Before Haase had even returned home from the airport, he began receiving calls from the media. He’d been told by police not to say anything because of the ongoing investigation. But he wanted to be accountable and explain that he was not involved.

He recalls: “They wanted to hear my story, from my side, because [de Jong’s] name was already known. … I didn’t want to have stories and things written that were untrue.” (Haase recalls that the onslaught of media calls abated later that afternoon when word broke about the death of Johan Cruyff, ironically, the uncle of Badr Hari’s former girlfriend.)

Haase says that, for weeks, he didn’t leave his home. He recalls going out for lunch and being recognized, so he walked with his head down. He was embarrassed, wondering whether he was recognized because he was a prominent international athlete or because his name was adjacent to a true crime story.

With a patchwork of coaches—a former junior coach, his father—Haase resumed playing, figuring that returning to work might serve him well. In retrospect, Haase says, he returned from this very different kind of injury too soon. At the annual Monte Carlo Masters, Haase lost his first match, unable, he says, to sustain concentration. For weeks, he had tamped down his emotions as he spoke to police and reporters. But in the locker room after the match, his release valve kicked in. “I started crying like a baby,” he says.” I wasn’t ready to play. It was like when you have a car accident and you want to go straight into the car again. I have to go back on court. But mentally, I was off.”

By the 2016 French Open, Haase’s stress level was so high that, he says, he was using the restroom 40 times a day. He lost to the American player Jack Sock, in front of dozens of Dutch journalists. Haase knew they were there to speak with him after the match, and not about tennis. But he faced their questions and was pleasantly surprised. “I have to say the sports press was really nice [that day],” he says. “It was kind of a relief because I was so tense. I really felt what stress can do to the body.”

Over the next year, Haase spoke to investigators multiple times as they built their case against his former coach. Once, he received a call minutes before walking onto the court for a match. Haase wonders whether the stress played a role in this mid-match outburst that went viral.

He emphasizes that, overall, other players were empathetic. But one colleague once saw Haase in a tournament restaurant and asked whether he should hide his knife. “I didn’t like it at all because it was, for me, a humorless joke—if you can call it a joke. But I didn’t blame him because everyone deals with certain situations in a different way. And he just didn’t know how to handle it, if he could just say, ‘Hey Robin, how are you?’”

Haase worked with a life coach and underwent considerable emotional spadework. He didn’t blame himself. Until he did. Maybe he should have parted earlier with de Jong, which he considered doing in late 2015. Maybe he could have picked up signs that his coach had a gambling problem— “I knew but I didn’t know,” he says—but he had no inkling it could lead to murder. Maybe he should have taken a longer break from tennis. In a quest to find that incremental difference, he switched rackets—which he now says was a mistake. He never found favor with the injury gods. He also has the misfortune of playing at a time coinciding with the three most accomplished players of all time. But it sure didn’t help that he had this unwanted role in a true-crime scandal. “It felt like I was in a movie,” says Haase. “A bad one.”

Haase did not speak to de Jong after his arrest. Asked about de Jong, by both the media and Dutch police, Haase was careful to provide facts but no opinions or speculation about his former coach’s guilt or innocence. One year to the day after de Jong’s arrest, Haase wrote a poignant blog post that read in part: “It took me a while to play tennis without thinking about the whole situation. … This was not an easy time in my life.”

Andre Weening/BSR Agency/Getty Images

Meanwhile in the Netherlands, the murder case against de Jong proceeded. While in prison awaiting trial, de Jong called his parents to inform them that he had hidden an IWC watch, a brand that Everink was known to have worn, in his sister’s bedroom. De Jong requested they get rid of the watch somehow. Unbeknownst to de Jong, police had tapped his parents’ phone.

Asked at trial about the watch, de Jong responded that he had found it in his car the day after the murder. Asked why he had not reported the watch to police when he was initially questioned, de Jong responded, “In hindsight, I should have said things differently.” Otherwise, de Jong stuck by his story, denying any role in the murder.

A panel of judges in Utrecht found otherwise. In January 2018, de Jong was found guilty of murdering Everink with his own kitchen knives. “The suspect robbed Everink of his life in a gruesome manner,” the chief judge said. “ It must have been terrible to be attacked in your own home by someone you trusted.”

In sentencing de Jong to 18 years in prison, a strikingly harsh punishment by Dutch standards, the judges made specific reference to the fact that Everink’s daughter was present. “She heard her father screaming. It must have been clear to the suspect that the little girl would find her father dead.”

De Jong appealed the verdict. On March 22, 2019, the Appeal Court sentenced de Jong to 20 years imprisonment, rejecting his claims that he had been kidnapped and the kidnappers had killed Everink. De Jong appealed again, pushing his case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the appeals court had erred in rejecting his request for a further investigation. On May 26, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the trial was conducted properly, and the verdict of the lower court was maintained. Today, de Jong sits in prison, still proclaiming his innocence.

Not far from the facility, Badr Hari, now 38, still trains as a kickboxer. After serving his prison time for assaulting Everink, he resumed his career. Elsewhere, a Dutch girl, now 12 years old, continues to mourn her father.

As for Robin Haase, in the years since the murder he managed, at times, to reenter the ATP’s top 50 and remain well, dangerous. He has beaten top players like Daniil Medvedev, Alexander Zverev and Casper Ruud. He has won dozens of matches, all over the world, in both singles and doubles. “I definitely got to a better place,” he says.

But he’s still processing these last few years. While it’s not a favorite topic of conversation, he recognizes that his friend’s murder at (literally) the hands of his coach is part of his story. “Still now, it’s strange,” he says. “Last week I dreamt about [de Jong]. It happened. I talk about it. It’s not like I’m holding it back. I’m not scared of It. But yeah, it still affects me in a way, I guess.”

Haase recounted this in the lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel in September. He’d come to New York for the U.S. Open, as a doubles player. With his girlfriend watching, he won his first two matches, lost his third and flew to the next event in France, hoping to wring a bit more from his career.

He’s 35 now. On most days, his body wages a kind of civil war against itself. His tennis odometer is down to its last clicks. He will never take the title at Wimbledon or the French Open as he’d hoped when he turned pro. And still, here he stands, proof that you can win in sports without hoisting trophies. For as often as sport figures talk about overcoming obstacles and getting beyond distractions, here’s an athlete who faced the most unusual disruption you could cook up. And he resumed his career.

He must be awfully proud of this, no? He pauses and exhales. “I obviously wish I’d never been in this [situation],” he says. Another pause. “But I guess when you put it like that, yes. I am proud.”

Additional reporting by Pieter Van Twisk.