Sydney World Pride and Mardi Gras 2023 were a huge success. Sydney was activated in a way rarely seen – block and street parties, cultural festivals and dance parties for all tastes. Now that the beats have diminished and the glitter has settled, viewing Pride (R)evolution at the State Library of New South Wales made it all the more richer and remarkable for me. This show is an astonishing survey of the importance of difference.

Pride (R)evolution is one of just five serious, in-depth exhibitions about queer culture held in Sydney during Pride: the others were curator Margot Riley’s William Yang’s Sydneyphiles Reimagined, University of New South Wales’ The Party – about the rich seam of Sydney’s club and dance parties from the 1970s to the 1990s, National Art School’s Queer Contemporary, including Richard Perram’s major exhibition, and the Powerhouse’s Absolutely Queer, with a focus on non-binary dressing and the current generation. It was the smaller, more agile spaces that held these significant shows, and not the larger, prominent galleries, such as has been happening in Melbourne.

Libraries and archives are incredibly important spaces as they can actively work to reflect the diversity of their constituents. The State Library of NSW has been collecting and analysing queer stories for decades. As gay life in NSW was criminalised until 1984 and policed much longer, much of the story survives in court records, sensationalist reporting, and traces left behind by queers themselves. Pride (R)evolution is remarkable for seeking out new voices via the queer community and reconnecting a whole series of broken threads.

It also tells the story of “good people” who are queer-friendly or queer-adjacent and who believed these stories deserved to to be saved. At the height of the AIDS crisis, many gay men died without a legal will and their life records were often destroyed. Some of those trailblazers include former Mitchell Librarian Margy Burns, an out lesbian who believed in “voices from below”, and library curator Sally Gray, who developed protocols to preserve the work of creatives.

Archives and memories

Since Margot Riley lead-curated Coming Out in the 70s in 2019, State Library staff have been involved in a major push to bring in new collections and voices in time for World Pride. At the same time, the queer community itself has become intent on conserving its archives and memories – such as a major archive building opened in Melbourne in 2021.

A curatorial collective worked with a consultation group of 30 community figures, activists and creators to bring in stories from across Sydney, including western suburbs and South Asian voices.

Curators such as Bruce Carter distilled the most powerful words and images from hundreds of metres of archives and thousands of images.

Queering the State Library

The exhibition opens by queering the whole organisation: we have a section on Ida Leeson, the sapphic-appearing Mitchell Librarian (1932-46) who was the first woman to hold a senior post in an Australian library and who lived openly with Florence Birch, YWCA official – Leeson’s private papers were burned by her family.

A multi-path layout allows visitors to take any path they wish, complex and tracking in different directions like many queer lives. Bright, primary colours reflect the energy and activism of the lives we are about to meet.

How did we meet before apps? We learn about communication in the pre-digital age with the formation of both gay and lesbian presses, examples of classified ads, phone lines, and computer dating services.

Who was present? We learn about Indigenous Australian involvement in Mardi Gras: Malcolm Cole, who featured as Captain Cook in the 1988 Mardi Gras, and who was the first Indigenous man to be commemorated with a death notice in the gay press in 1995.

What about anti-violence initiatives? I had forgotten we were encouraged to wear whistles, as the violence had become so bad by the early 1990s. The whistle necklace became a fashion cue, an example of resistance merged with style politics.

Authentic and domestic lives

How was all this social change cobbled together in the pre-internet age? Original painted and collaged designs for Mardi Gras posters highlight a messy materiality.

There is a strong “Do it yourself” and agitprop aspect to much of the work that meshes with postmodern irreverence and the blurring of boundaries.

Art, craft, design, jewellery, performance, fashion, fun: labels didn’t matter, and no one really cared what they were doing or wearing so long as it enabled them to better live an authentic life.

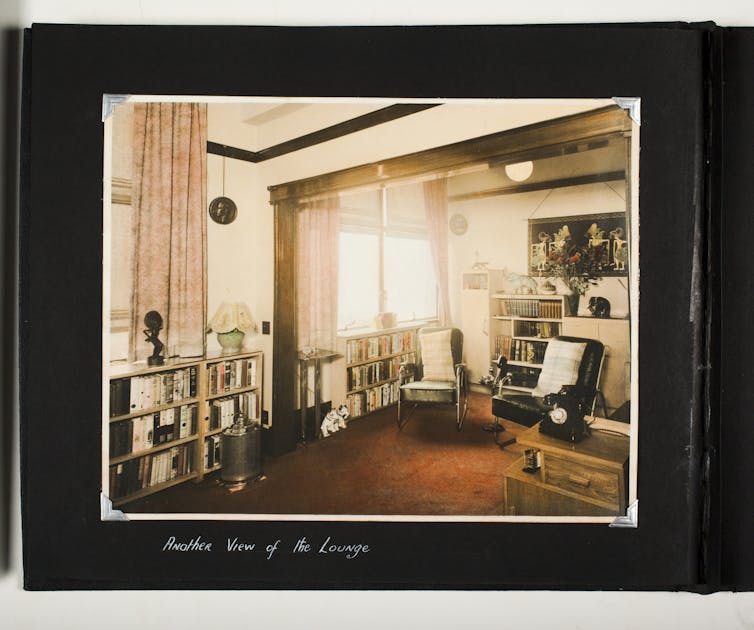

Gay lives are also domestic lives. There is that great rarity, a 1938 photo album of the modern furnished Astor apartment of Fred James and George Anderson, a couple who had met in Hollywood and were in the beauty business.

There is also a terrific section on 1970s gay share houses as spaces for “reinvention and kinship”.

Sound and voices

Sound features strongly in the exhibition. There are voices drawn from oral histories and even soundbites from gay community radio and helplines. We can listen to a recreated lecture by important gay activist and historian Garry Wotherspoon. These digital assets allow for intergenerational understanding and transfer.

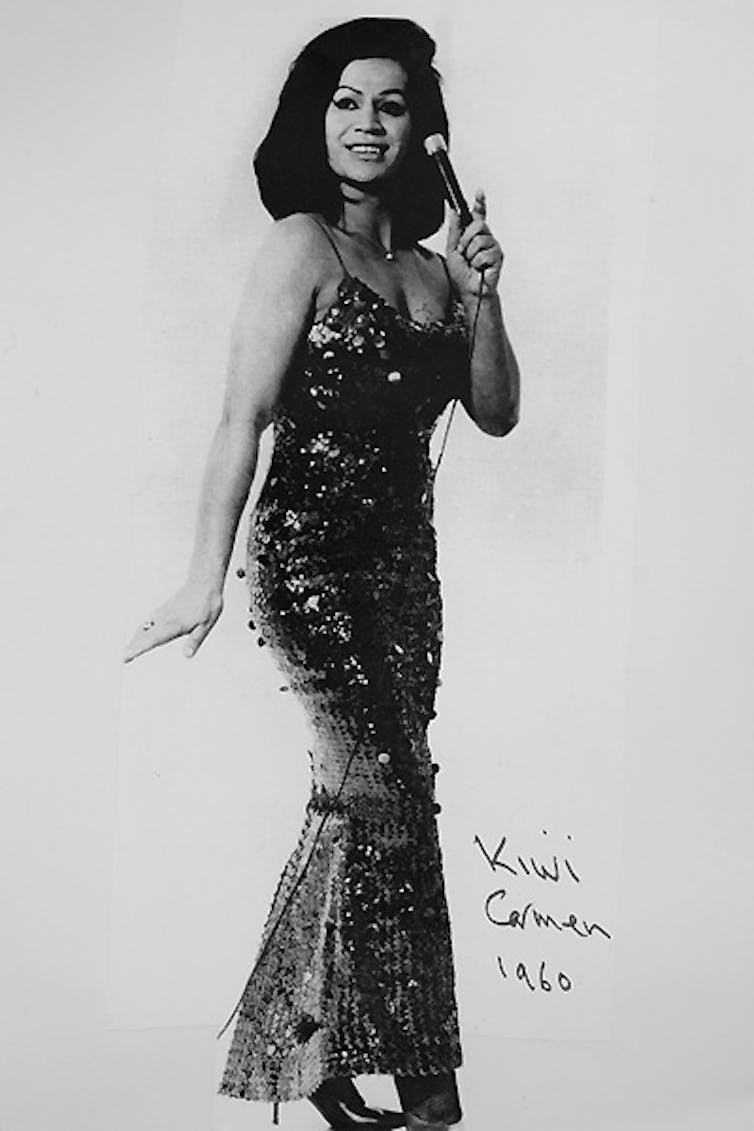

Drag queens have been called the “social workers” of the gay community for the work they undertook advocating for queer people during the AIDS crisis. Their stories, including of the sex work they often undertook, are told respectfully with reference to figures including famous Whanganui Mâori trans woman Carmen Rupe (I miss her darting around on her motorised scooter, tropical flowers in hair).

Not alone in history

Incredible 1970s photographs of the transfeminine community of Kings Cross taken by the theatrical designer Bary Kay are shown for the first time. We learn about Roberta Perkins, a trans woman who advocated for sex workers’ rights. NSW was the first jurisdiction in the world to decriminalise sex work in 1995.

“Predecessors confirm that you are not alone in history”, notes Archie Barrie. Pride (R)evolution is a live example of how collections and archives enable citizenship.

People have a right to be seen and find themselves in public institutions: “you are each living your own stories”. This intergenerational dialogue permits us to see how far we have come, how the “personal is always political, and the private often becomes public”.

Peter McNeil does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.