Doomsday is an evocative word for a grim idea, and it’s hard not to be spooked by the knowledge that the Doomsday Clock is currently set at 90 seconds to midnight. According to its operators – the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – who monitor the combined risks of nuclear annihilation, climate disaster, biological threat and disruptive technologies, we have never been closer to global catastrophic destruction since the clock’s founding in 1947. Oof.

And yet, humanity has a primal instinct to survive. Anyone in doubt of this bold statement would do well to hotfoot it to Mudac – the Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts – in Lausanne this month, where a compelling new show, ‘We Will Survive’, demonstrates in glorious breadth and depth that we are a resilient species. Or we are doing our utmost to be as prepared as is humanly possible for disasters of all scales, from blackouts and biological warfare to full-scale, four-horsemen apocalypse.

In a State of Prepare: discover the exhibition 'We Will Survive'

The show introduces us to the ‘prepper movement’, preppers being the term for people who prepare for catastrophe. It is a practice that has been on a rapidly upward trajectory since the dawn of the atomic era, aided by wars, climate change, terrorism, pandemics, rolling recessions, technology and the media. Today, ‘prepping’ is mainstream – a global movement and industry – and the value of the preppers industry is growing globally seven per cent year-on-year, due to reach $2.46bn by 2030.

Anniina Koivu – who co-curated the show with Jolanthe Kugler – stumbled across the subject of preppers in a 2017 article in The New Yorker which discussed the boom in emergency shelter construction in the US.

When you start to look, you find initiatives and examples of preppers everywhere

Anniina Koivu

She quickly discovered the parallel world of prepping that runs alongside daily life in dedicated stores, online communities and in-person gatherings right up to government-led plans and strategies. ‘It is just out of sight, but when you start to look, you find initiatives and examples of preppers everywhere,’ she says. She has been immersed in the subject ever since.

By way of a preview, Koivu curated a ‘Prepper’s Pantry’ with Mudac for Salone del Mobile last year, in the suitably bunker-like Dropcity, a new centre for architecture and design beneath Milan’s main station. Amid the excess of furniture and frivolity that week, the objects she showed demonstrated a sobering reminder that design has an essential role in survival, not just titivation. There is nothing glamorous about toilet paper, instant noodles or duct tape, but even the cleverest of sofa systems is unlikely to save anyone in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

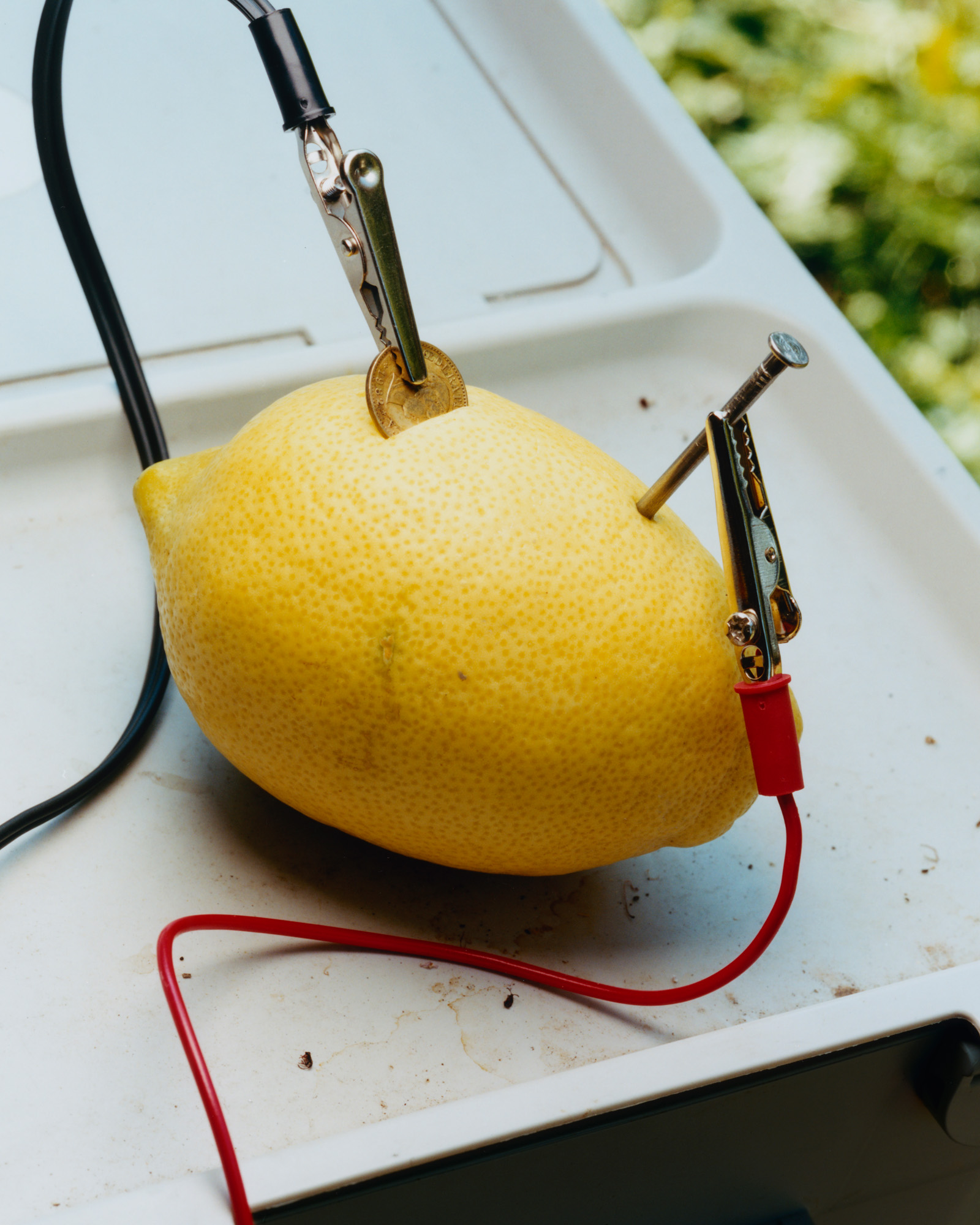

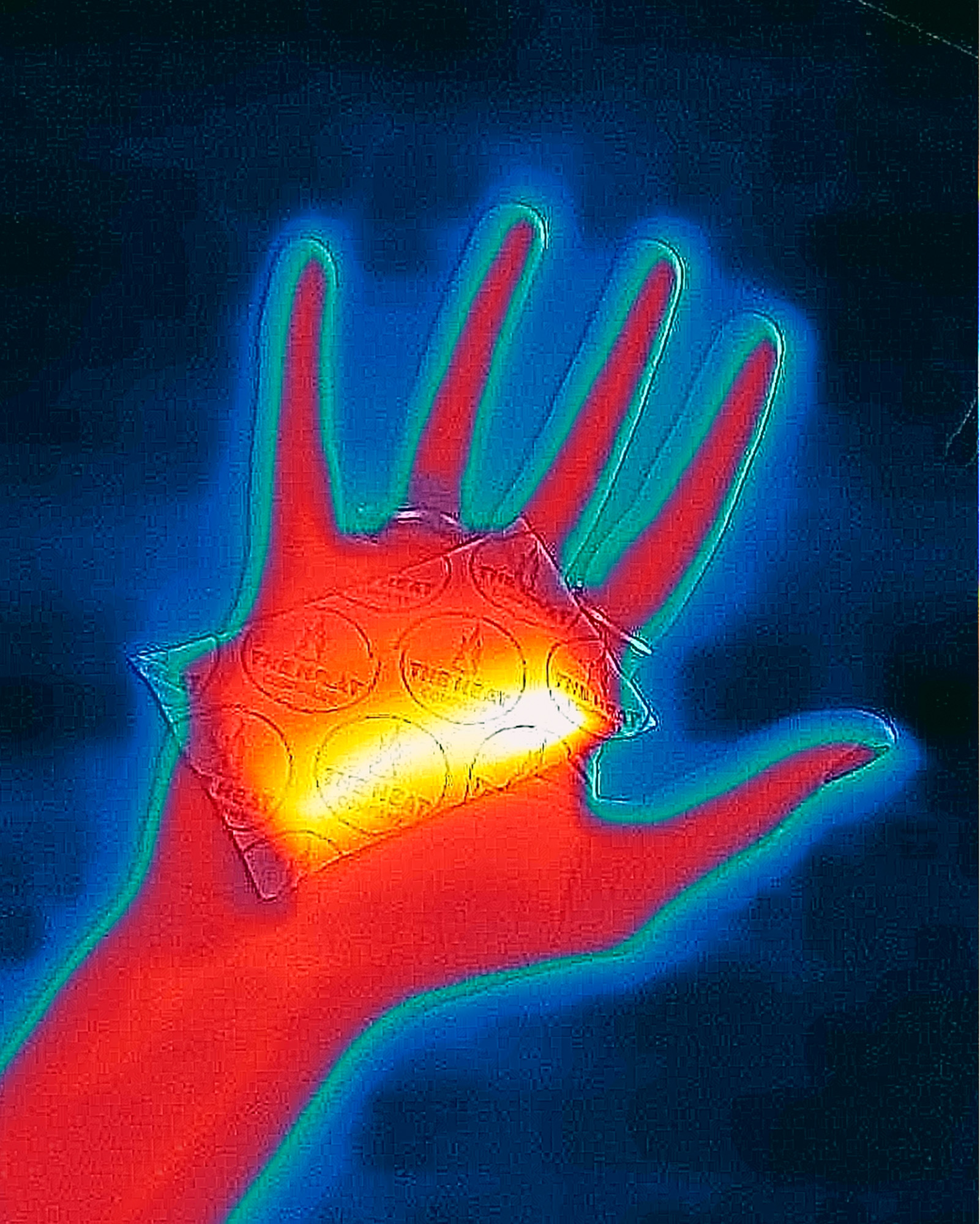

For the Lausanne show, the pantry has swollen to become a supermarket for objects that save lives, with the objects displayed in a taxonomy that follows an established sequence of categories necessary for survival: water; food; hygiene (including health and mental health); skills; tools; energy, heat and light; shelter, protection and rest (including comfort); and finally, communication, navigation and transport.

Koivu is quick to point out that the selection is by no means definitive. ‘Together, these objects provide a glimpse into the world of objects designed for survival,’ she says. ‘Different scenarios and time frames have been taken into account, including short-term evacuation, such as for wildfires or hurricane warnings; medium-length confinements at home, such as a pandemic lockdown; situations that necessitate fleeing, like chemical spills or violent attacks; situations that require coping in the wilderness for an indefinite time; and long-term stays in underground fall-out shelters in the aftermath of a large-scale disaster.’

The objects will be displayed on shelving from a decommissioned Migros supermarket, which lends its own weight to the show; the failure of institutional convenience such as supermarkets is one of the more tangible triggers for prepping, as any pandemic stockpiler can attest.

We feel we can buy our survival

Anniina Koivu

‘The supermarket felt like a fitting context for the show because when disaster strikes, we go shopping,’ says Koivu. ‘We feel we can buy our survival.’ Meanwhile, photographer Charles Negre has taken a series of still-lives of prepper products, which will appear alongside the exhibition, encouraging us to look anew at the beauty in a tin of Spam or a toothbrush.

Beyond commerce, Koivu and Kugler have also included a layer of important ‘How to…’ instructions for fundamental survival tactics, from tying knots to sourcing and purifying water. Outside the supermarket are a series of case studies that introduce institutional and governmental prepping responses. These include the Swiss National Redoubt, a defensive plan providing shelter space in the event of an invasion; the evacuation plan of the area around Mount Vesuvius if it erupts; and a specially commissioned film by Tapio Snellman, detailing the underground masterplan developed by Helsinki, which contains a skatepark, swimming pool, running track, shopping mall, museum, gallery spaces and even a church.

It is testament to Koivu’s deft curation that the subject feels fascinating to the point of optimism, rather than mawkish or doom-laden. This is the same Koivu who set Milan alight during the 2018 Salone with her show ‘U-Joints’, celebrating the subject of connections, literally and beyond. Her approach to curation is simultaneously forensic and generous. ‘I enjoy looking at subjects that have bigger implications, but I’m careful not to be judgmental,’ she says. This approach steered her away from covering the more radical fringes of the prepper movement, but far from ignoring the uglier social dimensions of the subject, she has diligently surfaced the essential and unequivocal, using the lens of design for parsing a sector, rather than human paranoia as a source of entertainment.

As such, the exhibition is a celebration of ingenuity and resilience, albeit with a nod to the eerie, and Koivu has worked in collaboration with her cohort at ECAL (where she is head of master theory), with installation design by Camille Blin, Anthony Guex and Christian Spiess, and graphic design by Frederik Mahler-Andersen.

Everything is almost as it should be, but then you notice things are just a little uncanny.

Anniina Koivu

She points to the show’s graphic identity to demonstrate how a fairly archetypal sans serif font has been warped slightly with all the vowels tilted to the left. The effect is just mildly sinister. ‘SNAFU was our guiding principle for the show’s design,’ she explains. ‘It’s a military acronym that stands for: ‘situation normal: all fucked up’.’ Everything is almost as it should be, but then you notice things are just a little uncanny. The effect is like opening a friend’s cupboard to get more wine and realising they have been stockpiling baked beans for the apocalypse.

‘It has to be an optimistic project,’ says Koivu. She namechecks two books that helped her see the light in a potentially dark field. ‘Hannah Ritchie’s Not the End of the World looks at data not news, and suggests we are not nearing the end of the world at all, which is a relief.’ Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell is similarly enlightening, examining the fallout from tragedies such as Hurricane Katrina and noting that a fundamental sense of community emerges from catastrophe. ‘Our instincts are to help each other, not to steal our neighbour’s jewellery box.’

Are we all preppers to some degree? And are we better-prepared generally now, thanks to our pandemic-induced rediscovery of more primal skills, such as planting, cooking and mending? ‘I think we’ve come to appreciate aspects of life that we had maybe taken for granted,’ muses Koivu. ‘I’m from Finland, where being in nature, prepping for winter, preserving and salting are part of our annual rhythm. You plan ahead for more difficult times. This is ingrained in us as an instinct for survival. Very few of us live on a day-to-day survival strategy in modern times. Prepping is really just a healthy way of life – so long as you don’t tip overboard into obsession or science fiction.’ Less a call to arms or panic then, and more a gentle directive to keep calm and learn how to pickle. It’s just the prep talk we need.

‘We Will Survive’ is on show from 13 September-9 February at Mudac, Lausanne, mudac.ch