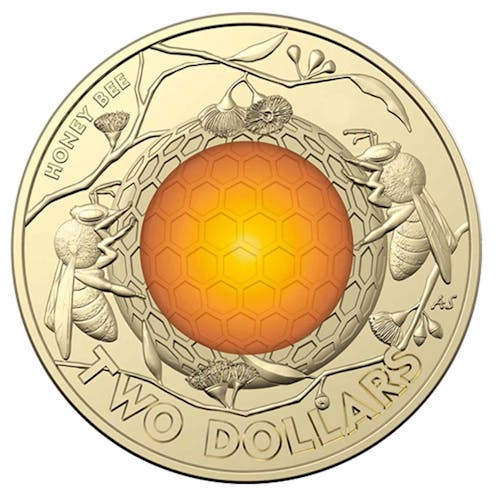

The Royal Australian Mint has released a $2 collectors’ coin to celebrate 200 years since the introduction of the European honeybee.

At the time of writing, one of the 60,000 uncirculated coins was selling for as high as A$36 – but that’s not the only sting in the tail of this commemorative release.

The coin celebrates an invasive alien species, and continues a long tradition in Australia of romanticising introduced fauna.

Meanwhile, we’ve missed an important opportunity to showcase Australia’s native pollinators, some of which are threatened with extinction.

Honeybees: two sides of the coin

The coin was released to mark the bicentenary of Australia’s honey bee industry. Honeybees were introduced to Australia by early European settlers and there are now about 530,000 managed honeybee colonies.

The commercial honeybee industry provides pollination services to a range of crops, as well as honey and beeswax products.

But the industry comes with costs as well as benefits. The introduced honeybee can escape managed hives to establish feral populations, which affect native species.

In New South Wales, feral honeybees are listed as a “key threatening process”.

Honeybees can take over large tree hollows to build new colonies, potentially displacing native species. Tree hollows can take many decades to form and bee colonies occupy hollows for a long time – so this is a long-term problem for native bees.

Many other native species also rely on tree hollows for shelter and breeding, and are likely to be affected by competition from honeybees. They include at least 20% of birds including threatened species such as the superb parrot and glossy black cockatoo, as well as a range of native mammals and marsupials.

Honeybees, both feral and managed, also compete with native species for nectar and pollen in flowers. Research has shown honeybees often remove 80% or more of floral resources produced.

Read more: Phantom of the forest: after 100 years in hiding, I rediscovered the rare cloaked bee in Australia

Unrealised pollinator potential

As others have noted, farmers around the world have become “dangerously reliant” on managed honeybee hives to pollinate their crops. Overseas, honey bees colonies are declining due to threats such as parasites, loss of habitat, climate change and pesticides.

While Australia has been sheltered from some of these threats, relying on a single managed pollinator is still considered risky.

For example, Australia is the only inhabited continent free of the varroa mite, a parasite implicated in the collapse of overseas bee colonies.

Should the mite become established in Australia, it could lead to agriculture industry losses of $70 million a year. Fortunately, the varroa mite has little impact on native species.

Read more: Explainer: Varroa mite, the tiny killer threatening Australia's bees

Australia is home to a range of native pollinators, including bees, butterflies, and bats, which all contribute to the $14 billion pollination industry.

Some – such as Australia’s 11 species of stingless bees – can produce honey – though not to the extent honeybees can. They can also pollinate blueberries, macadamias and mangoes.

In fact, some native bee species can nest on the ground in stubble and other parts of crops. In contrast, honeybee hives are often trucked from crop to crop.

And best of all, pollination by non-commercial native species is free.

A recent study found the common native resin bee is a suitable lucerne pollinator, and that small, ground-nesting nomiine bees were more efficient at pollination than honeybees. Pollination by stingless bees also may result in heavier blueberries.

While these studies are promising, more research is needed to assess the potential of native pollinators.

Read more: 'Jewel of nature': scientists fight to save a glittering green bee after the summer fires

Feral horses: a true national icon?

This is not the first time an Australian coin has commemorated an invasive species. This year, the Perth Mint released a collectable $100 coin to celebrate Australian brumbies – or feral horses – which it described as “national icons seen by many as symbolic of our national character”.

Brumbies have long been an object of affection in Australian culture, including romanticised depictions in movies and poems such as Banjo Patterson’s The Man From Snowy River.

In recent years this has translated into a campaign to protect feral horse populations, which can wreak havoc in fragile ecosystems such as NSW’s Kosciuszko National Park.

The damage includes trampling endangered ecological communities, causing soils to erode or compact and sending silt into streams. Feral horses drive away native species such as kangaroos and can wipe out populations of threatened native species.

Like feral honeybees, feral horses are listed as a key threatening process in NSW. They’re also considered a potentially threatening process in Victoria.

Which species should we celebrate?

When species are featured on a coin, it elevates their profile, engenders public affection and, according to the Royal Australian Mint, helps “tell the stories of Australia”.

Australia’s native species are tenacious – often the underdog fighting for a fair go in a harsh environment. Surely that’s a story also worth telling.

In response to this article, chair of the Australian Honey Bee Industry Council, Trevor Weatherhead, said the Royal Australian Mint “took the opportunity, after representation from our industry, to highlight a very important pollinator that makes an enormous contribution to the Australian economy […] If people want other pollinators to be on a coin then they can approach the mint to do so.”

Eliza Middleton receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

Caitlyn Forster receives funding from the Australian Research Council and is a board member for the Australasian Society for the Study of Animal Behaviour.

Don Driscoll receives funding from DPI NSW, DELWP Vic, National Geographic, Rufford Foundation, and Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC. He is Director of the Centre of Integrative Ecology at Deakin University. Don is a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and Society for Conservation Biology.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.