Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump claimed in August 2024 that a photograph of a large crowd of supporters welcoming Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris to Detroit on Aug. 7 was doctored. Trump falsely wrote on Truth Social that the crowd did not exist because “she ‘A.I.’d’ it.”

Multiple independent news sources, including Reuters and the BBC, confirmed that the photograph was not created by artificial intelligence. The large crowds at other Harris rallies also suggested that this turnout was not an anomaly. But minuscule details such as the apparent lack of reflections on the plane made some conspiracy theorists skeptical.

Trump himself came under fire after fake, AI-generated images made by his supporters of him amid crowds of smiling Black supporters circulated. But even if Trump seems willing to share fake images, he does not have a monopoly on the practice.

After a bullet grazed Trump’s ear on July 13, for instance, some people – including those who identified as anti-MAGA activists – shared social media posts and memes asserting the false idea that the assassination attempt was staged.

These kinds of accusations – that fake-looking images are real, that real-looking ones are fake – have been a common feature in politics, particularly among extremists, especially since the early 20th century.

That’s when it first became technically possible to routinely print photographs in newspapers and magazines. During this era, a new form of media blossomed, as magazines began using photographs, rather than just drawings, for illustration purposes. These magazines were particularly popular during the Weimar Republic, a government in power in Germany from 1919 through 1933, before the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, most often known as the Nazi party.

During the 1920s, Germany experienced an unstable economy, parliamentary paralysis and an increasingly polarized society.

During this economically and politically tumultuous time in Germany, photo manipulation in popular news publications – particularly one run by the Nazis – was rampant.

The rise of the Nazis’ publication

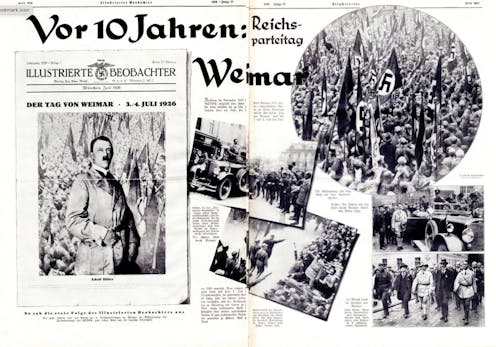

I am a scholar of Germany, and as part of my research on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, I have been researching an idiosyncratic Nazi propaganda magazine called the Illustrated Observer – or, in German, the Illustrierter Beobachter.

The Nazis, who formed as a political party in 1920, started publishing this magazine in 1926. The magazine, published through 1945, provides valuable historical context for understanding today’s political mudslinging about fake and doctored photos. It also shows how, left unchecked, publishing fake information could potentially contribute to dire political consequences, such as a rise in fascism.

As the Illustrated Observer’s name suggests, it belonged to a genre of publications that Germans call Illustrierten, literally translating to “illustrateds” in English.

These magazines included serious news stories and photojournalism, but also short fictional stories, jokes, cartoons and crossword puzzles. And because of advances in printing technologies, they also included lots of photographs.

These glossy, stylishly illustrated tabloids were so popular in Germany that the most popular publication, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung – or Berlin Illustrated Newspaper – had a circulation of 1,844,130 copies each week by 1929.

The actual readership numbers surpassed this figure, as multiple people in homes, hotels and cafés in Germany would share copies of the newspaper.

‘Who lies?’

In July 1926, the Illustrated Observer published a spread that included eight large photographs of a Nazi rally held in the town of Weimar. It included one photo that was taken with a wide-angle camera lens that exaggerates the crowd’s size.

Alongside this camera trick, the Nazis also used misleading captions and photo cropping to skew how people would likely interpret this and other photographs.

The Nazis were still a small political party in 1926, but they were steadily gaining power, and this sort of photographic trickery helped fuel their rise.

The caption for the photo that shows a crowd of people at the Nazi rally hatefully shouts: “Who lies? Photography or the Jewish newspapers?”

With this question, the Illustrated Observer aimed to discredit centrist newspapers, which accurately reported that the rally was a noisy and violent affair attended by hooligans, whom one journalist mocked as “Hitler-people.”

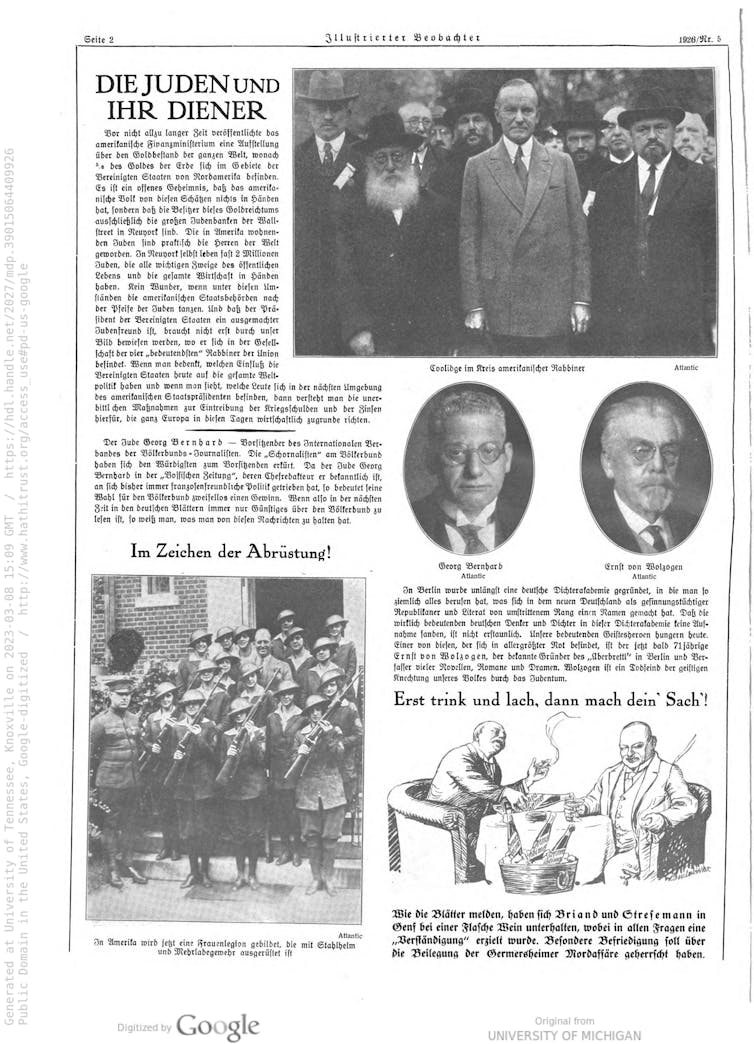

A few months later, the Illustrated Observer’s Christmas 1926 issue included a story headlined “The Jews and their servants.” A tightly cropped photo showed U.S. President Calvin Coolidge surrounded by about a dozen rabbis, who were dressed conservatively and had top hats and thick beards, traditional for Orthodox Jewish men.

But this was not the full story. The photograph was cropped, and the original image showed a much larger group portrait of more than 100 people who attended a religious Zionist meeting at the White House. Through cropping and misleading headlines, the Illustrated Observer falsely tried to show that a small, conspiratorial group of Jews controlled the American president.

A flashback to the 1920s

These kinds of photo manipulations were common during the final years of the Weimar Republic, Germany’s first but ultimately failed experiment with democracy that left the doors of power open to the Nazi takeover in January 1933.

The Nazis effectively used a visually striking mix of incendiary words and images in their magazine to constantly sow the seeds of doubt among readers. It was hard to know which photographs were real and which were fakes – and, thus, who was telling Germans the truth and who was not. This practice eroded confidence in the news, fueled further conspiracy theories and made it hard to know which political party to trust.

These conflicts from a century ago will sound familiar to people following the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

Now, there are also claims of doctoring images, angry rebuttals, accusations of media bias and an intense, conspiratorial fixation on details that supposedly expose certain images as fakes.

To some, the knowledge that the current political trend of photo doctoring is not new may make it easier to dismiss this as a fact of life in politics. But to others, the ominous historical consequences of unchecked photo manipulation might be too significant to ignore.

Daniel H. Magilow receives funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities in the form of a faculty fellowship.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.