In the spring of 2019, I led a team to the Chinese side of Mount Everest to try and solve one of mountaineering's greatest mysteries: Who really was the first to leave their boot prints on its summit? Officially, the tallest mountain on Earth was first ascended by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary on May 29, 1953. But there has always been a chance that pioneering British mountaineers George Leigh Mallory and Andrew Sandy Irvine, who were last seen at 28,200 feet on June 8th, 1924, still "going strong" for the top, might have beat them to the punch. Mallory and Irvine, wearing wool and gabardine, hobnailed leather boots and homemade oxygen sets, disappeared into a swirling cloud on that fateful day, never to be seen alive again. Ever since, the question of whether they might have made the top before falling or succumbing to the elements has stirred the collective imagination of the mountaineering world.

In 1999, my friend Conrad Anker discovered Mallory's remains at 26,700 feet on a rubble covered snow ledge on the North Face of Everest. Mallory was face down, his fingers dug into the gravel, with a severed rope tied to his waist. His partner, though, was nowhere to be seen, and nor was the infamous Vest Pocket Camera (VPK) they were said to be carrying. Technicians at Eastman Kodak have long held that the film, deep frozen for decades, might still be salvageable. Might that film show Mallory, ice axe held triumphantly over his head, standing on top of the world?

Armed with new research, a set of GPS coordinates, and specially modified high-altitude drones, my team set out to find Sandy and the camera in May of 2019 — to try and solve this mystery once and for all. At 27,700 feet, I left the security of the fixed ropes to make a solo climb out to the coordinates — only to discover that there was nothing there.

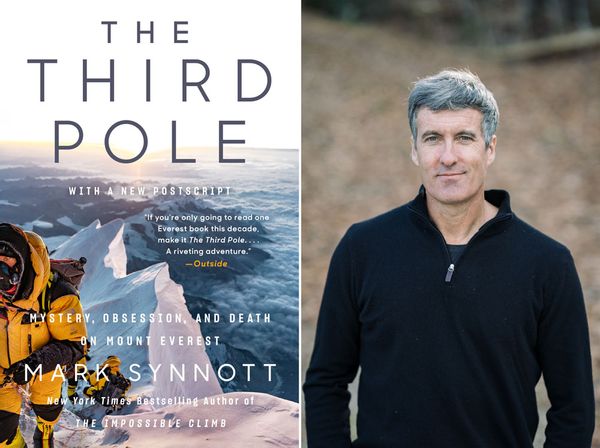

After the expedition, as I worked on my book, "The Third Pole: Mystery, Obsession, and Death on Mount Everest," I kept hearing rumors that explained why I didn't find Sandy: The Chinese had found his body and the camera long ago — and then buried the story. An official with the Chinese Tibet Mountaineering Association told a Nepali friend of mine in the fall of 2019 that the rumors were true. The camera was kept under lock and key, with other Mallory and Irvine artefacts, in a museum in China. Unable to let go of this story, I made arrangements to fly to Lhasa to interview a high-ranking official in the CTMA. I had plane tickets and hotel reservations when the novel coronavirus began spreading in Wuhan, China. My trip was cancelled, and it was unclear when or if I would ever have a chance to conduct these interviews.

Dear Mr. Synnott,

My name is Wayne Wilcox. I'm a former Marine officer, former US State Department Regional Security Officer, and retired corporate security director, now living in England with my wife and two boys. . . . My wife works for the British Foreign Office. Since 2008 I've been sitting on some information that I think would make a good story. With your new book out, I feel that you are the logical person to tell it. I'm not a real writer, I don't have the time or resources to research and write it, and I don't have the clout to get it published, but it's a story that I think should be told.

Wilcox went on to explain that his source, a high-ranking official in the British Embassy, had direct knowledge that the Chinese found the remains of a foreign climber at 8,200 meters during their 1975 expedition to the North Face of Mount Everest. And on that person, they had recovered the long-lost Kodak VPK and brought it back to Beijing. Wilcox also wrote: "They screwed up the development of the film and ruined it. Rather than admit they made a mistake, they erased all evidence that they had found the camera or the body."

I immediately reached out to Wilcox and learned that in 2008, Wilcox and his wife, Juliette, were stationed in China. As a diplomat with the British Foreign Service, Juliette was invited to attend the opening ceremony of the summer Olympics at the Beijing National Stadium. The event lasted over four hours and included more than 15,000 performers. Toward the end, the Olympic flag was carried in by eight Chinese national heroes. One of whom was a petite Tibetan woman in her late sixties.

After the ceremony, Juliette met up with a seasoned British diplomat who told her that he recognized the Tibetan woman. "That was Pan Duo," he said. "She was the first Chinese woman to climb Mount Everest." This man, whom I will call "the diplomat," noted that when the other flag bearers waved to acknowledge the Chinese leaders, Pan Duo had conspicuously abstained. This small detail had caught his attention, because years ago he had interviewed Pan Duo, and she had told him an interesting story.

It took months, but I eventually made contact with this diplomat. He agreed to share his story with me on the condition that I not reveal his identity.

The diplomat's interview with Pan Duo had taken place in 1984 at the headquarters of the Chinese Mountaineering Association (CMA; later to become the CTMA) in Beijing. The meeting had been arranged at the behest of Sir George Bishop, who at the time was the president of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). Bishop was a former British civil servant and businessman. He was also a skilled photographer and mountaineer who took part in eighteen expeditions to the Himalayas.

There were two Chinese representatives of the CMA at the meeting, Pan Duo and Wang Fuzhou. Fuzhou was one of three men who made the first ascent of the North Face of Everest as a member of the 1960 Chinese expedition. At the time of the meeting, he was the president of the CMA. Pan Duo was the second woman of any nationality to climb Mount Everest (missing out on being the first to Junko Tabei of Japan by eleven days) and the first to do so via the North Face. She grew up in western Tibet. Her father died when she was a toddler. By age six, barefoot and shabbily clothed, she was working in the fields, subsisting on a single barley cake per day and sleeping with yaks. In 1959, she was twenty years old and working on a state-owned farm when her physical strength and work ethic caught the attention of recruiters looking for trainees to join the fledgling Chinese mountaineering program. Later that same year, Pan Duo summited Mustagh Ata, a 24,636-foot mountain in Xinjiang. At the time, it was the highest elevation ever attained by a woman. On the descent, Pan Duo survived an avalanche that killed five of her comrades.

The British diplomat is the only person still alive who attended this meeting at the CMA. When we spoke over the phone in October of 2021, he told me that he couldn't remember a single thing about Fuzhou; Pan Duo, on the other hand, had made an impression. He remembered her as being "tiny" and having a beautiful, high voice. The one detail that he never forgot is that Pan Dou and Fuzhou said that on the 1975 Chinese expedition to the North Face of Everest, the team had found the body of Sandy Irvine and the Kodak VPK, which they brought home. Later, Chinese technicians attempted to develop the film but were unable to recover any images.

As all members of the British Foreign Service are trained to do, the diplomat took thorough notes at the meeting. He later wrote a memo, which he sent to Sir George Bishop and possibly the Foreign Office, but the document has disappeared. I searched the RGS; the diplomat pored over the UK National Archives for days; I was even in touch with Sir George Bishop's relatives, who told me that Bishop's widow burned all of his papers upon his death. As of this writing, the document remains unconfirmed.

I have, however, obtained an email that the diplomat wrote to the British Ambassador to China, Sir Anthony Galsworthy, on May 6, 1999. At the time, the story of Anker's discovery of George Mallory was spreading like wildfire across the globe. With all the speculation that was floating around about the missing camera, the diplomat wondered why Sir George wasn't coming forward with the information the two men had learned back in 1984. It wasn't until much later that he learned that Bishop had passed away on April 6, 1999, three weeks before Anker's discovery.

The subject line of the email to Ambassador Galsworthy reads: Did Mallory climb Everest?

"I don't have the answer to this question," writes the diplomat, "but just possibly I know how to find it [the camera] or to prove that it can never be found." The letter goes on to explain how Wang Fuzhou and Pan Duo told the diplomat and Bishop that the 1975 Everest team had recovered the camera. "We asked whether it had been possible to develop the film. I seem to recall that we were told there had been nothing on it. I also recall that we were told that the camera was in the Mountaineering Association's museum. Someone should speak with the Chinese Mountaineering Association. This was all a long time ago and I could have got it wrong, although I don't think so. And that meeting has always stuck in my memory. If the film really was mucked up, I imagine it is quite possible that the association [CMA] would deny that the camera had ever been found."

It is also possible, if not likely, that the film revealed Mallory and Irvine high on the mountain, perhaps even on top. This, of course, would rob the Chinese of the first ascent of Everest's North Face, an accomplishment that occupies sacred space in the hearts and minds of the Chinese people

When Wayne Wilcox was chasing this story back in 2008, he arranged for the editor of The Economist's China desk to interview Pan Duo. That interview took place through an intermediary shortly after the conclusion of the Beijing Olympics. The following is a shortened transcription that has been edited for length and clarity.

Economist: Roughly where on Everest did you discover the body?

Pan Duo: Probably at around 8,200 meters.

Economist: What was the condition of the body at that time?

Pan Duo: It was a foreigner, and he had a yellow zhangfeng [tent] with nothing else inside. The things had probably already been carried away.

Economist: When you saw the body, did you judge he had slipped on his way down from the summit, or did he die in some other way?

Pan Duo: He probably froze to death.

Economist: What about the camera?

Pan Duo: I don't remember the details of this . . . We buried him under a pile of stones: it wasn't bad. We stood there freezing. The body lay on the floor, when we went to pull him, maybe spleen or whatever, all would have been damaged. We considered it and then put small stones on his body, to show our grief/mark the grave.

Economist: And what about the camera?

Pan Duo: After we came down, we didn't see anything. Maybe others discovered it. I don't know.

Like most other clues in this mystery, this interview offers more questions than answers, but we do have Pan Duo admitting that the team found and partially buried the body of a foreigner in 1975 at around 8,200 meters. And we know that there was no one other than Mallory and Irvine who had died this high on the mountain. She doesn't admit to finding the camera, but it's likely she may not have been speaking as freely as she did with the diplomat back in 1984. As I detail in my book, by 2008 the Chinese were no longer acknowledging that they had found any bodies high on Everest during the 1960 and 1975 expeditions — even though we have testimony from several Chinese climbers to the contrary.

About a month after I spoke with the diplomat, I managed to track down Dechen Ngodrup, a CTMA official who had been on the mountain with us in 2019. I told him about the recent revelation regarding the camera and asked him if he knew anything about it. He said he didn't, but that he knew Pan Duo personally. "She is an amazing lady in China," he wrote. And she was, before she passed away in 2014. After her Everest climb, which cost her three of her toes, Pan Duo told a reporter, "Chinese women have a strong will; difficulties can't stop us. We climbed the highest peak in the world; we really hold up half the sky." She went on to be elected five times as a deputy to the National People's Congress. In 1981, she moved from Tibet to eastern China, where, as the vice director of the Wuxi Sports Administration, she trained the next generation of aspiring Chinese mountaineers, one of whom was Dechen. In 1986, she told the Beijing Review that she missed her home in Tibet terribly and was still struggling to adjust to the climate and the food in Wuxi. "Compared to Han cuisine," she said, "mountaineering is simple."

Dechen told me that Pan Duo had never mentioned the camera to him, and he did not know of it being in a museum in China. But he promised me that he would ask the surviving members of the 1975 expedition. I have not heard back.

If the camera was found in 1975, one possible place for it to reside is the Tsering Chey Nga Snow Mountain Museum in Lhasa. I don't know of anyone who has been to it, but I found a program online from Chinese state TV that offered a guided tour of sorts. Some of the historical items that are shown in this program are artifacts that have not previously been reported. Of course, I'd like to visit this museum and ask its director point blank about the VPK. But the COVID-19 pandemic continues to restrict travel to China, which remains, as it so often has, firmly closed to foreigners.

My own Everest journey has come to an end, but as I write these words from my desk in northern New Hampshire, I can't shake the possibility that someone, perhaps a high-ranking official in the CTMA, might know the answer to mountaineering's greatest mystery. Perhaps the Chinese do have the camera and they developed the film before destroying it and erasing the evidence forever. Or, maybe, those photos still exist, locked away in some vault in Lhasa or Beijng. Of course, given the present trajectory of geopolitics, the VPK might as well have fallen into one of the gaping crevasses at the bottom of the North Face, so slim is the likelihood that the Chinese government would reveal to the world what's on that film.

And so, I am left with only my imagination and the vision of Mallory and Irvine, still "going strong" for the summit — despite the late hour of the day, and the odds stacked terribly against them.