The Delhi High Court last week sought the Centre’s response to a petition challenging a government notification that requires married women to submit a no-objection certificate (NOC) from their husbands if they wish to legally change their surnames back to their maiden names.

A division bench comprising Acting Chief Justice Manmohan and Justice Manmeet Pritam Singh Arora ordered the government to file its response by May 28, when the matter will be heard next.

The case once again exposes the gendered fault lines within existing regulations that often presume that married women must take on the identity of their husbands. Although a highly prevalent practice now, research shows that the tradition of women changing their surnames post-marriage is relatively new to India. In a 2005 paper, sociologist Raja Jayaram noted that naming practices in India began to get standardised under the influence of British colonial rule. “The British colonial system expected the Indians to have both personal names and surnames, corresponding to their own naming system that consisted of a first name (e.g., John), a middle name (e.g., William), and a last name or surname (e.g., Goldsmith),” he wrote.

In her book “Seeing Like a Feminist,” writer and academician Nivedita Menon attributes the practice to India’s patriarchal caste system. “The emergence of the universal ‘surname’ as part of the homogenising practices of the modern colonial state and the wife taking the husband’s name as a natural and unquestionable part of marriage amounts to the gradual naturalisation of two dominant patriarchies – North Indian upper-caste and British colonial,” she wrote.

However, recent data suggests that there is a gradual shift in this social convention. A survey conducted by the matrimony app Betterhalf.ai in 2022 showed that 92% of the respondents considered it normal for married women to not change their surnames after marriage.

Also Read: What’s in a surname?: On a woman’s right to choose her own identity

An undated government notification

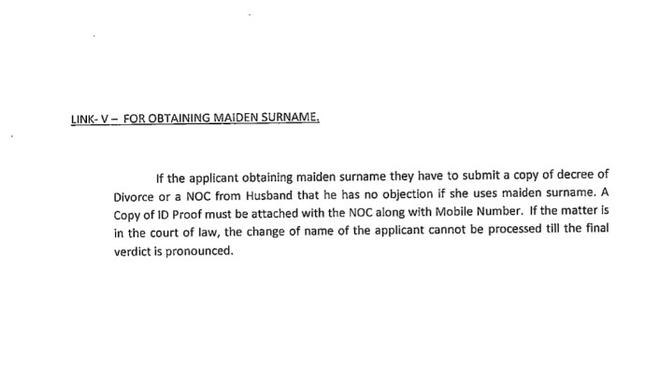

The notification in question was published by the Department of Publication of the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) and stipulates that a woman seeking to legally change her name back to her maiden name has to either submit an NOC from her husband or a copy of her divorce decree. A copy of her identity proof along with her contact number also has to be submitted along with the NOC. If divorce proceedings are pending, then such an application would remain on hold until the case is concluded.

The notification is titled “Change of Name (Major & Minor), (Change of Sex, Change of Religion, Public Notices for Correction of Name, Adoption of Child), specifically under the category “Change of Maiden Surname.”

Surprisingly, it is neither dated nor is it known why it has been issued by the MoHUA, since this falls outside its ambit. Ruby Singh Ahuja, Senior Partner at law firm Karanjawala & Co. and Advocate-on-Record at the Supreme Court, who represents the petitioner in this case, told The Hindu that even her legal team was unable to find out when the notification was published.

‘Patently discriminatory’

The petition has been filed by Divya Modi Tongya, a 40-year-old Delhi-based woman who legally took her husband’s surname in September 2014. In 2019, she changed her name to include both her maiden as well as her husband’s surnames. In August last year, she filed for divorce under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, before a Delhi court and wished to revert to her maiden surname during the pendency of the proceedings.

However, owing to the “arbitrary nature” of the government notification, she was unable to do so without obtaining an NOC from her husband. She challenged the notification before the Delhi High Court, demanding a direction to quash it.

Her petition contends that the notification violates a host of fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution under Articles 14 (equality before law), 19 (protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc.) and 21 (protection of life and personal liberty.) Highlighting its “patently discriminatory” nature, Ms. Tongya argued that the notification displays “evident gender bias” by imposing additional and disproportionate requisites exclusively on women.”

The Court was also apprised that by imposing a restriction that is contingent upon the passing of a verdict in divorce cases, the notification introduces an element of arbitrary delay that impinges upon the prompt exercise of a one’s right to choose her name.

According to Ms. Ahuja, the notification also constitutes an invasion of privacy since it requires women to submit their contact details, which is not a necessity at all. “Why must the husband’s permission be sought to exercise a fundamental right? If a man has to change his surname, does he require anybody’s permission?” she asks.

She also points out that it creates an irrational classification between women who did not change their names after marriage and those who did, but later wish to revert to their maiden names.

Judicial precedents

This notification is part of a larger systemic problem that is also reflected when married women who retain their maiden surnames access government services— when opening a bank account, getting a passport, or availing ration facilities, among others. But courts over time have attempted to ease this disproportionate impact by clarifying that there is no legal mandate for such a practice.

In JigyaYadav v. CBSE (2021), the Supreme Court recognised that the ability to change one’s name is an important facet of the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19 of the Constitution. An individual must be in complete control of her name and the law must enable her to retain as well as to exercise such control freely for all times, it underscored.

Also Read: Spousal consent not must for organ donation: court

In an obliquely-related case, the requirement of spousal consent through the issuance of NOCs for organ donation by women was overruled by the Delhi High Court and the Madhya Pradesh High Court in 2022. Justice Yashwant Verma of the Delhi High Court asserted that insistence on such a requirement would impinge upon the right of a woman to be in control of her own body.