Steven Soderbergh wants to show you something strange.

One of our most eclectic — and prolific — modern filmmakers, the Oscar-winning director of Traffic, Contagion, and Logan Lucky has worked in every genre and at every budget level, whether he’s crafting high-gloss heist pictures (Out of Sight, the Ocean’s trilogy), neorealist experiments (Bubble), or paranoid thrillers of a modern persuasion (Unsane, Kimi). Since first emerging into the rough-and-ready ’90s independent film scene with Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Soderbergh has proven himself an agile, compelling presence inside and outside of the studio system. And, having averaged one film or series a year since reemerging from a short-lived hiatus in 2017, including both conspiracy-thriller miniseries Full Circle and sci-fi comedy web series Command Z in the past six months alone, he shows no signs of slowing down.

But beyond his hot streak on television, Soderbergh is paying it forward at the box office this fall, furthering his long-established track record of working with other directors to help them realize their most radically experimental visions. As executive producer of Eddie Alcazar’s Divinity — a bizarro, black-and-white sci-fi saga — and Godfrey Reggio’s Once Within a Time — an anarchic, avant-garde fairy tale from a legend of nonnarrative filmmaking — Soderbergh is granting his seal of approval to two films unlike any other you’ll see this year.

Soderbergh’s Divine Intervention

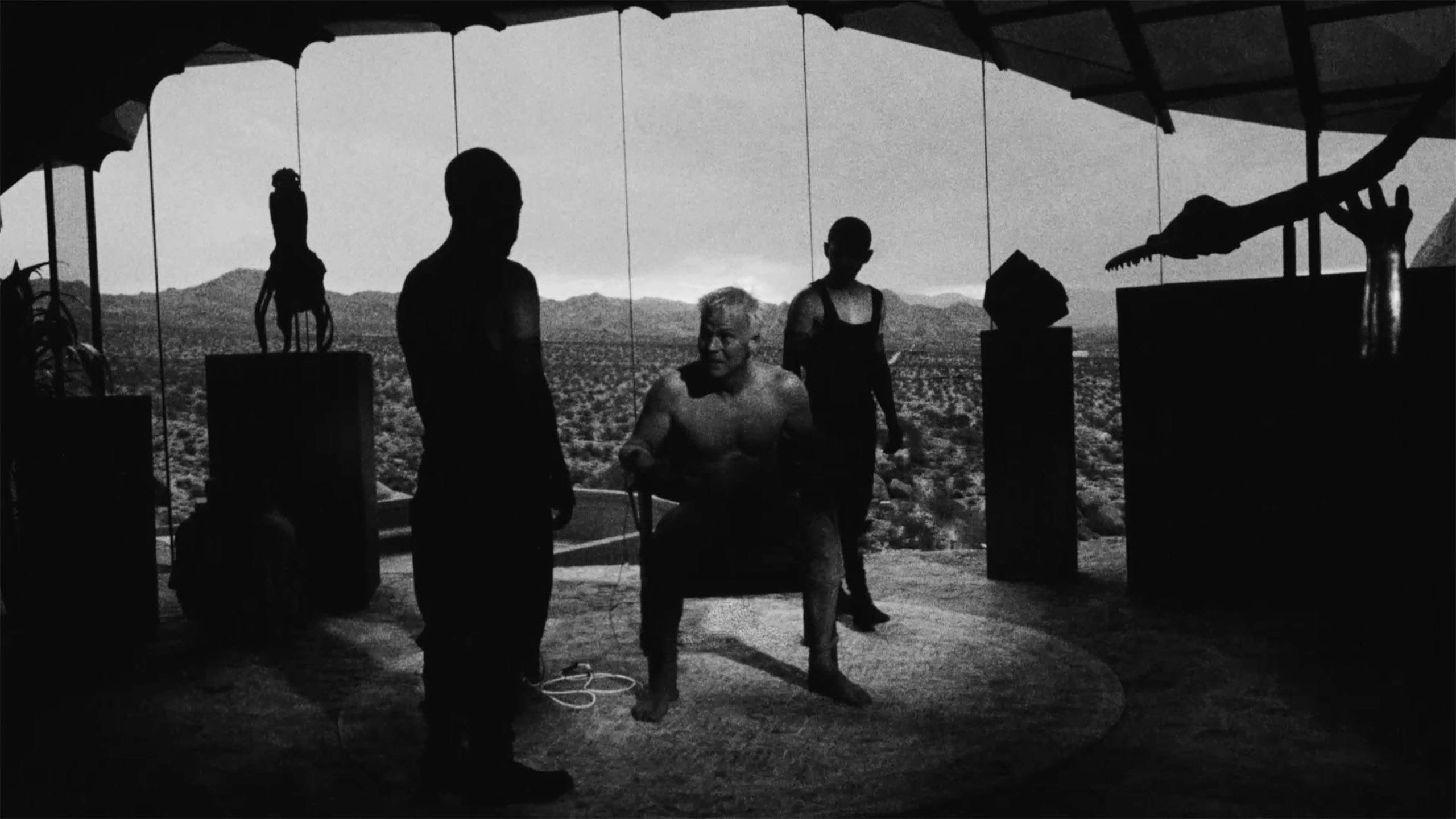

Set in an otherworldly future where a groundbreaking immortality serum has given humanity physical perfection but also left it barren, Divinity (now in theaters; expanding nationwide Nov. 4) is a retrofuturist head-trip that plays much like a transmission from an alien world. Shot in vintage black-and-white on specially made film stock, and featuring an alternately ethereal and oppressive synth score by hip-hop pioneer DJ Muggs and David Lynch collaborator Dean Hurley, the film’s aesthetics are as stark and immersive as its sprawling themes of life, death, and uncertain reality.

Alcazar, also a co-founder of Flying Lotus’ Brainfeeder Films, tells Inverse that Divinity was “an impossible film to make” for a young independent filmmaker — until Soderbergh came into the picture. Alcazar first connected with Soderbergh after working with actor Chris Santos on his feature debut Perfect, set at a mysterious clinic where patients transform their bodies and minds with the aid of genetic engineering. Santos had starred opposite Sasha Grey in Soderbergh’s The Girlfriend Experience and sent the filmmaker an early cut of Perfect on Alcazar’s behalf, asking for his opinion. Shortly thereafter, Alcazar found himself meeting Soderbergh in Los Angeles, discussing his reaction to Perfect and how he could help contribute to its editing process.

“He wasn’t necessarily serving as an editor, but that was the easiest way for him to give notes and contribute ideas,” Alcazar says, noting that Soderbergh ultimately joined Perfect as an executive producer. “That was inspiring: to see his perspective, how it translated what I’d created, and what came out of what I’d initially made once I could look through his eyes.”

“Sometimes, I get stuck on certain things, I ask him about them, and I don’t really get a clear answer back. And that’s his point: That it’s my voice, and I have to define it and find my own answers.”

Soderbergh then made an offer that Alcazar still looks back on in complete disbelief: Without imposing any conditions as to its subject or aesthetic style, he would fund Alcazar’s next project. “It puts a lot of pressure on you when somebody gives you that much trust,” Alcazar reflects. “You really want to come through. But that’s what motivates me and keeps me on my toes.”

Soderbergh’s promise of creative freedom meant that Alcazar and cinematographer Danny Hiele could shoot in 16mm black-and-white reversal stock, made specifically for the production by Kodak; it also meant that Alcazar didn’t have to finalize a script before filming. Instead, the writer-director presented his collaborators with a basic treatment and storyboards, soliciting ideas from actors and crew members, and ultimately completed the film over the course of seven different shoots, in between which he edited footage and continued to explore new ideas. It’s thanks to that iterative process that Divinity was able to capture many of its most memorably stylized scenes, such as a fight-sequence climax that blends live-action footage, LED walls, and stop-motion animation in what Alcazar calls a “meta-scope” technique.

“He’s been so trusting,” says Alcazar, looking back on the collaboration with Soderbergh. “That's the biggest thing. He’s a great mentor in the sense that he lets you find your own way, and he doesn’t give you too much. Sometimes, I get stuck on certain things, I ask him about them, and I don’t really get a clear answer back. And that’s his point: That it’s my voice, and I have to define it and find my own answers.”

Once More, A Long-Awaited Collaboration

According to cinema legend Godfrey Reggio, who has worked with Soderbergh to release his own wildly experimental features for the past 20 years, it’s precisely that method of backing other filmmakers’ visions without influencing them that makes Soderbergh an ideal collaborator.

“He’s a man of few words,” Reggio tells Inverse, speaking by phone ahead of the release of his new feature, Once Within a Time (now in theaters). “If you write an email, he might give you all of two-word responses. He’s the real deal, and he doesn’t interfere. He lets you be free as a bird, gives you the final cut, and everything. He looks in on everything we do out of interest, not out of a desire to control.”

Reggio’s first film in a decade, Once Within a Time is described by its distributor, Oscilloscope Laboratories, as “a bardic fairy tale about the end of the world and the beginning of a new one, tinged with apocalyptic comedy, rapturous cinematography, unforgettable vistas, and the innocence and hopes of a new generation.”

Reggio, now 83, prefers to think of the hypnotic 52-minute feature, which forgoes easily decipherable dialogue throughout its cascade of ambiguous, awe-inspiring images, as “a symphony in three acts,” shifting between retellings of classical myths and reflections on the next generation’s embrace of technology. (Mike Tyson also makes a strange, mind-expanding cameo appearance.)

Reggio calls Once Within a Time his first comedy, made for children and their parents to watch together. Shot on a soundstage in Brooklyn, the feature fluidly moves between storytelling techniques — from animated miniatures to helter-skelter collage art, digital effects, and actors performing in front of a green screen — but all 112 of the film’s images “are made up of the aural and visual,” according to the director.

Once Within a Time is a long-awaited return to filmmaking by the director, best known for the Koyaanisqatsi trilogy, which explores the impact of modern technology and industrialization on society and the natural world. (In the Hopi language, koyaanisqatsi means “life out of balance.”) Among the most unique film debuts in American cinema history, Koyaanisqatsi can be described as a meditation on the state of humanity’s relationship to the greater world, one that draws its elemental power from juxtapositions of images and sound, depicting civilization’s transition from natural environments to technological milieu against music by the legendary experimental composer Philip Glass. It soon became a cult film; many consider it a masterpiece.

“I’ve learned as much from him as he has from me. We’re like inmates in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Soderbergh first saw Koyaanisqatsi in 1983, when it came out; a 20-year-old aspiring filmmaker at the time, he was mesmerized by the experience and later executive-produced several of Reggio’s films, starting with Naqoyqatsi, the final film in his Qatsi trilogy. Reflecting on how the two first crossed paths, Reggio claims that he “conjured Steven Soderbergh” in the early 2000s by speaking with Boston Globe film critic Ty Burr for a New York Times interview. In that conversation, Reggio spoke about the challenges of funding Naqoyqatsi, despite his grand ambitions for the planned third film of his Qatsi trilogy: “It’s like I’ve been given an enormous Rolls-Royce and a teaspoon of petrol,” he said.

“That afternoon, Soderbergh’s producer got in touch with Philip Glass, because he knew how to reach him,” recalls Reggio. “The next morning, I was in Los Angeles, sitting with Soderbergh and my producer, Lawrence Taub. His first question was ‘Do you have the emotional fortitude to go forward?’ Of course, I acted as if I knew what I was saying, and I said, ‘Of course.’ That’s where our relationship began.”

Reggio and Soderbergh’s collaboration now spans 20 years and three released films, also including 2013’s Visitors. Composed of 74 shots, depicting people’s faces in slow motion and landscapes evolving with time-lapse photography, Visitors, like all the rest of Reggio’s work, explored humanity’s trancelike relationship with technology. (At the time of its premiere, Soderbergh said, “If, 500 years ago, monks could sit at a bench and make a movie, this is what it would look like.”)

Reggio teases that another film, The Holy See, featuring Visitors’ same visuals but a different soundtrack — a Stradivarius cello, played by one person the whole time — could come out within the next year, as part of his collaboration with Soderbergh. “I’ve learned as much from him as he has from me,” reflects Reggio. “We’re like inmates in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Driving Hollywood ‘Outsane’

Both Divinity and Once Within a Time explore strange new worlds dominated by technology and in some ways ravaged by humanity’s relationship to it. Both employ experimental cinematic techniques that allow them to grapple with existential conflicts of modernity and tradition, past and future, and simulation and reality. And neither film could have been made by anyone else, at any other time; what unites the two most of all is an overriding spirit of sui generis innovation that Alcazar, Reggio, and Soderbergh consider all too rare in the American film industry today.

“Whether people love Divinity or hate it, what I’m most proud of is the fact that we’re doing something unique that could help push the medium forward in its exploration and hopefully motivate others to do the same,” says Alcazar.

“The guy doesn’t stop, and he gives his good luck away to other people who he feels share his outsane point of view.”

“Every artist just wants to get deep into their own work and know that they’ll be recognized for their form of expression,” he adds. “That’s a beautiful thing. If artists feel the work can be their own, they’re going to work that much harder to make it — because it’s going to be a representation of what they can do and what they love to show people.”

What strikes Alcazar the most about Soderbergh’s motives for investing in projects like Divinity and Once Within a Time is that, as a filmmaker who releases new films at a head-spinning frequency, Soderbergh has seen more than most how unfriendly studio filmmaking has become for experimental filmmakers.

“Working with Soderbergh makes me want to help others in the same way,” says Alcazar. “His is a great mentality to have in an industry so constricted by big, low-risk franchises and commercial cinema.”

Reggio agrees. “The guy doesn’t stop, and he gives his good luck away to other people who he feels share his outsane point of view,” says the director. “He’s a child that never grew up, like I am.”