The Kalhatti Ghat Road plunges into the Segur plateau on the outskirts of Udhagamandalam. The road aprons are ideal points for viewing the vast expanse of the magnificent plateau in almost its full splendour.

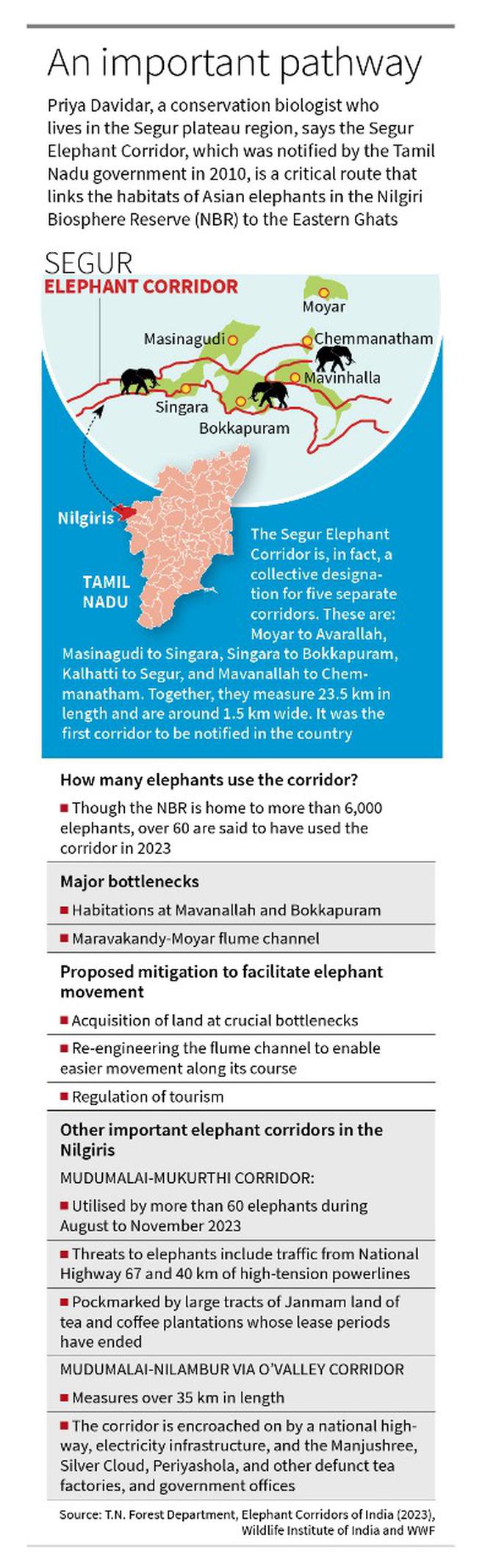

Looking down with a pair of binoculars from the 13th hairpin bend of the road, tourists can see the Kalhatti stream meandering down the plateau, eventually meeting the Sigurhalla River, the Moyar and the Bhavani Sagar Dam further downstream. The area, comprising Mudumalai, Nagarhole, Bandipur, Sathyamangalam and Wayanad, forms part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, a tract measuring over 5,000 square kilometre, which is home to the largest population of Asian elephants in the world, numbering over 6,000, says Priya Davidar, a conservation biologist who lives in the Segur plateau region. Ms. Davidar adds that the Segur elephant corridor, notified by the Tamil Nadu government in 2010, is a critical “elephant corridor that links these habitats to the Eastern Ghats”.

Orders on objections

A Supreme Court-appointed committee recently ruled in favour of protecting the corridor. It passed orders that declared 12 private resorts, along the corridor, illegal. The court had mandated that the committee, comprising a retired judge and two prominent conservationists, look into the objections raised by the owners of the 12 resorts who had challenged the validity of the elephant corridor notification. The committee passed its recent orders on the objections from the resort owners. The court had ordered the closure of 27 other resorts in 2018.

Ms. Davidar explains that the Segur elephant corridor is of global importance not only for elephants but also for other animals like tigers. “It is also home to the largest population of three critically endangered species of vultures in southern India.”

Illegal structures in land used by elephants

The Segur Corridor Inquiry Committee, in the orders passed against illegal resorts, said the resort owners had put up “illegal structures” invariably in the land abutting reserve forests and streams frequently used by the elephants. “...By erecting power fences, the resorts have hindered the movement of elephants in critical parts of the corridor.” The committee also said, “…unless their [Asian elephants] migratory corridors between their habitats are preserved”, the habitats would be fragmented, resulting in the extinction of the elephant population.

One of the main contentions of the resort owners was that parts of the elephant corridor did not comprise elephant habitats. But the committee highlighted the High Court’s observations while upholding the validity of the notification. “The High Court also held that any absence of elephants from the areas surrounding the appellants’ resorts was, in fact, due to the construction activities of the appellants, whereby access of the elephants has been restricted through erection of electric fencing,” the committee said.

Samuel Cushman, of the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at the University of Oxford’s Department of Biology, says in an email that wildlife corridors are often “networks of multiple and diffusive pathways that individuals use in part at different times... Corridor effectiveness is judged on how it facilitates movement across the landscape, which may include individuals traversing the full length of the corridor, or more often, traversing parts of it.”

The committee also flagged the apparent conflict of interest in one of the documents used by the resort owners to claim that the area in which the resorts were built did not comprise an elephant corridor. “…the Right of Passage report, heavily relied upon by the applicants, has been prepared by a non-governmental organisation — Wildlife Trust of India — in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and others. One of the trustees of the said organisation is also the editor of the report, who owns a property... in Bokkapuram, Sholur,” along the notified elephant corridor. It went on to add that while the editor had updated the number of elephant corridors in India from 88 to 101 in the second edition of the Right of Passage, he had “inexplicably” failed to include areas notified by the Government Order number 125, issued in 2010.

The committee said a closer analysis of the Right of Passage in 2017 revealed that the editor, who owns a property at Bokkapuram, which is surrounded by survey numbers wherein the resorts of the appellants are located, had omitted the specific portion of the corridor, though it was confirmed by the High Court in 2011. “The glaring omission of a specific portion of the elephant corridor cannot be overlooked and justified as normal,” it said.

Backbone of animal migration

Jean-Philippe Puyravaud, of the Sigur Nature Trust, says scientific methods to study elephant pathways , such as least cost path, factorial least cost path, circuit theory and landscape genetics have established that the regions between Masinagudi, Bokkapuram and Mavanallah form the backbone of animal migration, including that of Asian elephants, across the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. “I liken human settlements to the bubbles on Swiss cheese, around which animals have to pass to get to other parts of their habitat. It is not just a case of targeting one resort or house, but limiting the urban sprawl that results in elephant pathways being closed off,” Mr. Puyravaud argues.

Explaining how elephants prefer gentle, undulating slopes to move between habitats, Mr. Puyravaud says that if a settlement or building were to come up on such a pathway, it would result in disturbance to elephant movement. “Again, it doesn’t mean that all elephants will stop moving through the area. There might be a few individuals that do, but much of the population, including herds with young calves, will be discouraged from using these paths owing to noise, light and other factors that come up with urbanisation.”

Loss of livelihood

Despite the broad consensus on the need to protect the elephant pathways in Segur, the closure of the resorts has come at a cost to some of the Adivasi communities in the region. According to V. Maari, headman of Thottlingi village at Bokkapuram, the residents of the village and, to a lesser extent, the four surrounding Adivasi villages relied on the resorts as their primary source of employment. “Many of the families had jobs as cooks and cleaners, while the resorts sponsored the education of a few students at private schools. However, now that they have closed, the job opportunities have dried up and children have been admitted to government schools,” he says.

Mr. Maari says they were earning ₹20,000 to ₹30,000 each at the resorts, but have become daily wage workers. “Our fear is that once the resorts cease to function, we too will be forced out of the tiger reserve.” However, conservationists and Forest Department officials point out that the existing laws, including the Forest Rights Act, will ensure that the Adivasis will not be moved out of the buffer area of the tiger reserve.

According to N. Mohanraj, a Nilgiris-based conservationist, the Forest Department has been employing members of the Adivasi communities in the region as anti-poaching watchers and under eco-tourism initiatives organised by the government. He adds that with the closure of the resorts, the Forest Department should absorb more youths into its staff.

“The resorts hired these workers to do menial jobs, and it is imperative for the Forest Department and also the government to help the communities to farm and make a living from their land,” says Mr. Mohanraj. The Forest Department, he stresses, should utilise the skills of these communities in tracking wildlife and living off the land. “In future, when the Forest Department requires trackers and workers for protecting the forests, there should be enough people from the communities who have the skills and expertise. However, their skills will be lost if the communities leave the forests and work in non-forest jobs.”

When contacted, Justice K. Venkatraman, chairman of the Segur Plateau Elephant Corridor Inquiry Committee, said the committee had sent 203 final reports to the objectors, and some of the orders to the district administration. “We have passed conditional orders, allowing some people using their buildings only for residential purposes to stay there. However, we have ordered the closure of houses being used for commercial purposes,” he said, adding that the Adivasi houses inside the corridor were exempted from demolition and the members of these communities from eviction.

Over 40 buildings ordered demolished

According to sources, 40-50 buildings in the corridor, including resorts and residential houses, have been ordered demolished, while construction on farmland without the approval of the district administration has been banned.

Mr. Cushman adds that while preserving corridors are important, they “are best used as part of a comprehensive landscape-scale conservation design in which core habitat areas for the main population concentrations are prioritised and protected first, then these are often buffered to protect them from degradation or encroachment, and then they are linked with corridors designed to facilitate movement between the most important core areas”. The region around the Segur corridor is an important core area for the elephants. It should be identified, prioritised and protected along with other such core areas. Then corridors should be designed to link these pathways, he suggests.

A Forest Department official says that the committee’s orders have ensured the protection of the Segur corridor for generations to come. “You have to understand that it is not just a question of resorts and homestays, but what their presence in the landscape entails. These resorts draw thousands of tourists at weekends, leading to a huge pressure on the local ecology, waste management systems, and forest management.”

He hopes the orders passed by courts and the expert committee will also deter landholders in Segur from building illegal resorts. “There have been many instances in which elephants have died or been injured either in retaliation by tourism operators or by falling into sewage tanks and cutting themselves on litter discarded by visitors.”

On Friday, the resort owners again approached the High Court with a writ petition, challenging the orders passed by the committee. A Division Bench orally observed that unless the Supreme Court clarified whether the High Court could entertain the petition, it would not hear this case. It adjourned the case to October 6.