Three men, riding together on a scooter, arrive at the Osmania General Hospital (OGH)’s in-patient facility on a Tuesday afternoon. The one in the middle carefully gets off the two-wheeler and trudges inside, to an overcrowded, overworked out-patient department, supported on the shoulder of the pillion rider. The third man proceeds to locate a parking spot in a hospital so overcrowded he may have to park outside. The scene is reminiscent of a comical sequence from the 2009 Hindi film 3 Idiots, but is, in fact, a glimpse into the everyday experiences of people seeking medical care at Telangana’s top tertiary government hospital.

On the face of it, Hyderabad’s OGH is an institution, some of whose buildings date back to 1926, need help. Nearly a century on, the toilets are frequently flooded and often unusable, while patches of ceiling in almost all the buildings peel off and come crashing down. But when the Telangana government decided to demolish all the 29 buildings and bring up new ones with 1,812 beds, across the 24-acre campus, there was resistance.

Every day at the hospital kitchen makes food for approximately 900 patients. At the laundry, about 1,100 bedsheets are washed, ironed, and folded. It is this scale of operations that has stretched the limits of the hospital, originally built for 400 patients. Currently, each patient is accompanied by at least two attenders, adding further pressure to the system.

Vijayender P.S., who served as chairman of Telangana Junior Doctors Association (TJUDA) during his study period at OGH from 2016 to 2019, recalls a portion of the ceiling falling on a patient in 2017. “At that time, the hospital administration and the government called for a contractor and made temporary repairs. After that, such incidents continued to be reported from across the hospital. If the government had taken proper control of the situation at that time, maybe we would not have reached this stage where we have to talk about demolition,” he says.

The building, one of four in the city in the Indo-Saracenic architecture style, was envisaged and executed by Vincent Esch, an established British architect in India. The style was developed by the British in India, fusing elements of Islamic design and local materials.

Highlights

- One of the origin stories of Hyderabad’s famed Osmania Biscuits is linked to the Osmania General Hospital. According to this lore, the nutritionists at OGH baked the cookie in the hospital canteen. The crumbly yet crisp biscuit had a hint of salt and sugar.

- The OGH has in its forecourt a giant tamarind tree with a garden. A small graveyard with graves is also present. When the 1908 flood wreaked havoc, about 150 people clambered up the tree and survived the deluge. The tree is a marker of the event.

- A 1942 map shows how OGH was the hub for healthcare with the primary health care centres in Kamatipura, Dabeerpura, Khairatabad, Aliabad, and other places functioning independently and referring serious cases to OGH.

In 1866, when it was at another location and called Afzalgunj Hospital, people came in from across the Nizam’s Dominion that stretched to modern day Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh. The OGH is also part of the riverfront rejuvenation project initiated in the aftermath of the devasting September 1908 flood which claimed 15,000 lives. The other buildings along the stretch are the Kachiguda Railway Station, Telangana High Court, and City College.

“Without the series of domes of OGH, the landscape will not be the same. It is part of the identity of people and the city here. The Telangana High Court had ruled in the Irram Manzil case that heritage is part of identity. The existing buildings should be protected while another must be constructed to improve healthcare for a growing city,” says Sajjad Shahid of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage.

Buildings crumble, staff at work

Vijay Kumar, 46, an autorickshaw driver, has come from Bhalki, a town in Karnataka’s Bidar district, after he was diagnosed with kidney stones. Instead of heading to the nearest hospital in his home State, he chose to travel 200 km to get a consultation at OGH. His family has been coming here since 2006, when Vijay’s father fractured a leg.

Then, a relative in Hyderabad had urged them to come to OGH for treatment. “We hesitated thinking that it is a government hospital, and were unsure about the quality of treatment. At that time, the doctors at OGH were kind and helpful. That hasn’t changed even now,” says Vijay’s mother, who was also with him.

The in-patient facility at OGH, the Quli Qutb Shah Block, built in 1992, is a sea of humanity with patients inside and their attenders outside. The families bring food, eat together, and wash clothes right there. A pack of canines shares the space. “I have to stay vigilant at all times. People try to sneak in and go near the patient. I have to face the music if there are too many attenders crowding around a patient,” says a guard, shooing away men and women who make frequent trips to the facility for updates on their relatives’ health.

For Rahman, 35, from New Delhi, OGH spells cure. In 2020, when his three-year-old son suffered burns, the family brought him here. They were surprised at the quality of treatment and care at the hospital. When Rahman recently got injured in a road accident, his family knew where to take him. He says he is very happy with the medical care provided at OGH. His only grouse? The serpentine queues outside labs that take hours to move.

Break and make

In March 2022, the government, through the Municipal Administration and Urban Development Department, constituted a four-member committee to submit a structural stability report. The panel included engineers-in-chief of the Roads & Buildings, Panchayati Raj, and Public Health departments, and chief city planner, Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC).

The High Court intervened in May 2022, and stipulated that the committee include one member each from the Archaeological Survey of India and the Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad. This committee reached a conclusion in June 2022 that stated, “However the structure can be repaired and renovated so as to increase the life of the buildings. These can be put to use after taking up repair works, for non-hospital purposes. As it is a listed heritage building, appropriate conservation repairs are to be taken up under supervision of Conservation Architect.”

However, the Telangana government, in July 2023, constituted another high-power panel that included Home Minister Mahmood Ali, Animal Husbandry Minister Talasani Srinivas Yadav, and Hyderabad MP Asaduddin Owaisi, among others. This did not include the two independent members from IIT-H and ASI. This new panel’s report was submitted as a memorandum in the High Court on July 27, 2023, recommending that all the buildings on the OGH campus be razed and a new facility built instead. “…it was unanimously opined that the old building is unfit for any kind of patient care and the said building is to be removed along with other satellite buildings for development of alternative hospital building of 35.76 lakh square feet...” was the conclusion of this committee.

It used the word ‘removed’ instead of ‘demolished’ but the import was the same. On September 5, the State government filed a counter-affidavit in the High Court about its plan to demolish the old OGH building as well as the other facilities there to build a new structure.

“It will still not meet the needs of the patients who come to the hospital,” says a doctor from Telangana Junior Doctors Association-OGH branch. “The government’s proposal takes into account only the current demand. If we talk of healthcare access for more people, 1,812 beds will still fall short at times. The number of patients will definitely increase in future. The government should consider constructing at least a 3,000-bed hospital, given the patient count,” the doctor says, adding that it would also be pertinent to conserve the old structure because of its sense of history.

‘No future without a past’

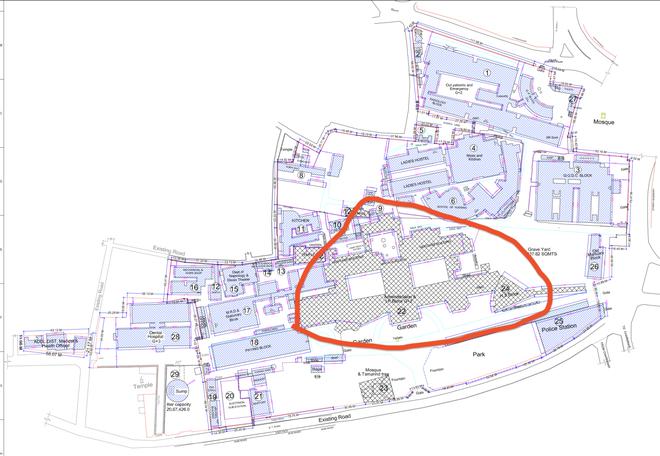

At his office at Jubilee Hills, Architect A. Srinivas Murthy shows a PPT with a series of images of dilapidated and derelict parts of the heritage block, including the grand dome with stained glass. Then he drops an image of a large rectangular block beside the layout map of the OGH complex.

“This is the 2,000-bed hospital block I have designed for a corporate group in Hyderabad following all the existing building bye-laws of the State. A similar facility can be built without disturbing the old buildings. Heritage is our past. Without our past, we are nothing,” says Murthy, who heads SMG Design, but is also the founder-president and CEO of Architecture and Design Foundation [India], a non-profit that promotes awareness of art, architecture, and design. “The idea is that the heritage structure needs to be protected however dilapidated the condition may be,” he says.

The hospital currently has 30 departments and 14 super-speciality services with nine hospitals affiliated to it — Modern Government Maternity Hospital, Modern Government Maternity Hospital, Niloufer Hospital for Women and Children, MNJ Cancer Hospital, Ronald Ross Institute of Tropical Diseases (Fever Hospital), Institute of Mental Health, Government General and Chest Hospital, Government ENT Hospital, and Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital and other facilities scattered all across the city.

The doctors at the hospital are aware of the shortcomings of the facility. A doctor, who recently completed his internship at the hospital, says many patients who are referred to OGH for surgery are sent back home and called just the day before as the hospital grapples with a shortage of beds. “Many get hospital-acquired infections while getting treated here,” another doctor admits.

Even as patients endure considerable hardship due to the hospital’s frail infrastructure, this suffering is equally shared by the medical staff, with female doctors encountering numerous challenges especially when it comes to accessing washroom facilities within the hospital premises.

“The management tries to keep the bathrooms clean despite the high patient load. Constructing a bigger hospital will help make provision for adequate washrooms, which is badly needed,” said a final year student of Osmania Medical College.

Plan of action

A senior official from the Health Department says that if the High Court gives the nod, the government will have two options to take the process forward. The first is to undertake demolition in two phases. Phase 1 will have the Quli Qutb Shah in-patient building and the out-patient block functioning as usual, while other structures including the heritage block are demolished.

Post demolition, construction of the new facility will begin. Once it is completed, preferably within a year, and ready for use, phase-2 will see the in-patient and out-patient buildings being pulled down and new construction taking place.

The alternative plan is to shift the entire operations to Government Hospital at King Koti and other hospitals affiliated to OGH so that the existing premises can be demolished in one go and a new modern super-speciality hospital can come up. This process will disrupt patient services as it will take about 15-18 months for construction works to be completed, the official adds.

“Whatever the government does, patient care should not be disrupted. That’s my only concern,” says a doctor at OGH, admitting that the present status of the hospital has become a divisive issue among the medical fraternity.