When ‘Tamil Maravan’ or ‘Tamil Yeoman’ (Cirrochroa thais) was named the butterfly of Tamil Nadu in 2019, it was a credit to years of efforts made by scientists, biologists and butterfly enthusiasts who painstakingly observed, documented and put together their thoughts in butterfly conservation in the Tamil landscape.

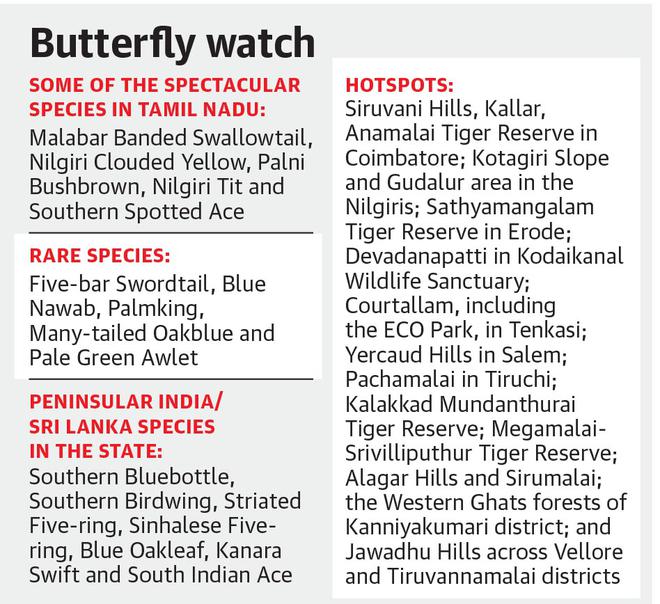

Tamil Nadu is home to 328 species of butterflies and the status of 322 of them has been revalidated as of now. The State boasts 95% of the 346 butterfly species that inhabit the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot.

“Many do not know Tamil Nadu is a butterfly-rich State. Tamil Nadu’s unique diverse landscape — which comprises the scrub, deciduous, evergreen to montane Shola and grasslands of the Western Ghats, the Deccan Plateau, the Eastern Ghats, the vast plains and long coastal lines — is the key factor in its butterfly richness,” says A. Pavendhan of The Nature and Butterfly Society.

Early accounts of butterfly documentation from south India supposedly started in 1758 when father of modern taxonomy Carl Linnaeus introduced a system of naming animals and plants, say experts. According to them, Crimson Rose ( Pachliopta hector) could be the first species described in all probability. Collections of butterflies from Tamil Nadu are now housed in museums of Europe and other places. Many of the south Indian collections were from the Nilgiris (Coonoor and Kallar), the Palani Hills and the Coorg Hills.

“Madras Government Museum in 1966 published a descriptive catalogue of butterflies wherein it is stated 228 butterfly specimens from south India were available. Many of the collections were from the Nilgiris, the Palani Hills, the Kalakkad region and Madras. Works of G.F. Hampson (1888), W.H. Evans (1932), J.A. Yates (1930s), G. Talbot (1939), Wynter-Blyth (1957), T.B. Larsen (1987-88) and many others need mention for south India, and especially for the Tamil Nadu region,” says Mr. Pavendhan.

“Some species, including the Spotted Royal and the Banded Royal, were spotted in the Nilgiris which we like to call as a ‘rediscovery’ as they were seen after several decades,” says Manoj Sethumadhavan of the Nilgiri-based The Wynter-Blyth Association. The Kotagiri slopes and the Gudalur region are butterfly hotspots in the Nilgiris. The upper reaches of the district are also rich in butterfly diversity. “We have been able to document the life cycle of Nilgiri Tit, which was found with a particular ground orchid as its host plant,” he adds.

Though parts of the Eastern Ghats are dry, they are also rich in butterfly diversity, according to S.R.K. Ramasamy, a Madurai-based farmer-turned-butterfly expert. “Many butterflies of the Western Ghats are also seen in the Eastern Ghats. This shows the Eastern Ghats hill ranges are also equally good in biodiversity and insect life,” he says.

According to P. Pramod, Senior Principal Scientist. Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), butterfly diversity and conservation are directly linked to plant diversity and their conservation. Each species has its own host plants. If plant diversity is lost, butterflies lose their larval food plants.

Habitat destruction as in the form of plantations, dam projects, degradation of evergreen forests through the spread of invasive plants, monoculture and habitat fragmentation, forest fires, use of pesticides and weedicides pose challenges to the gene pool.

I. Anwardeen, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, feels that securing the database on the species available in each habitat or forest division and monitoring the population diversity and distribution are important aspects of butterfly conservation. “Systematic butterfly surveys have been conducted in many divisions with the support of citizen science forums,” he says.

Surveys have been undertaken at the Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary, the Coimbatore Forest Division, the Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, the Erode Forest Division, the Salem Forest Division and in the Nilgiris in recent years.

“Host plants are very specific to each species. The Department has reoriented views from normal tree-based conservation, and the focus has expanded to other plants. Earlier what was thought to be parasitic weed on trees in the forest, namely Loranthus, is a host plant for Common jezebel. The size of the flower, floral tube and nectar content determine the size and type of butterflies that can visit the flowers for nectar. The Department is studying these nectar plants to augment their protection,” he explains.

The Department is focusing on awareness and capacity-building, too. An open butterfly garden was established in Tiruchi and another one in the Vandalur zoo. Small butterfly gardens have been set up at Aliyar in Coimbatore and the Kurumbapatti Zoological Park in Salem.

Mr. Pramod also stresses the need to have systematic studies on the migration of certain butterflies. “The Western Ghats sections of Tamil Nadu witness migration of several species every year. We do not have a clear idea of these phenomena which need a focused study,” he adds.

While 247 species were documented in the Siruvani Hills, Kallar boasts of 206 species. Coimbatore district has one of the highest species count, at 281. There are many areas with a checklist of more than 150 species. Butterfly enthusiasts and forums like TNBS look forward to the government declaring the Siruvani Hills a butterfly sanctuary, highlighting the importance of sacred groves and green parks within the city scape. The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, covers about 443 butterfly species and subspecies. Out of the six Schedules in the Act, butterflies are found in three Schedules — I, II and IV.

Schedule I, the highest protection status, covers Crimson Rose, Common Mime, Malabar Banded Swallowtail, Blue Nawab, Danaid Eggfly, White-tipped Lineblue, and Orchid Tit. About 60 species and subspecies from the butterflies that are found in Tamil Nadu are covered by the Act. This is about 18% of the total species count in the State and a majority of them are placed under Schedule II.

Experts feel more species need protection; hence, the Schedules may be revised soon, based on reassessment. Only two species, Nilgiri Tiger and Malabar Tree Nymph, have been assessed to be ‘Near Threatened’ by the The International Union for Conservation of Nature. More species must be assessed for their status in India, they feel.