The shriek of a whistle sounded an end and a beginning.

On an October night in 2015, reporters, curious out-of-towners and even satanists assembled at, of all places, a high school football game in suburban Washington state. They were all stoked for an impending collision, the crescendo of a fight that, over just six weeks, had ballooned into a spectacle.

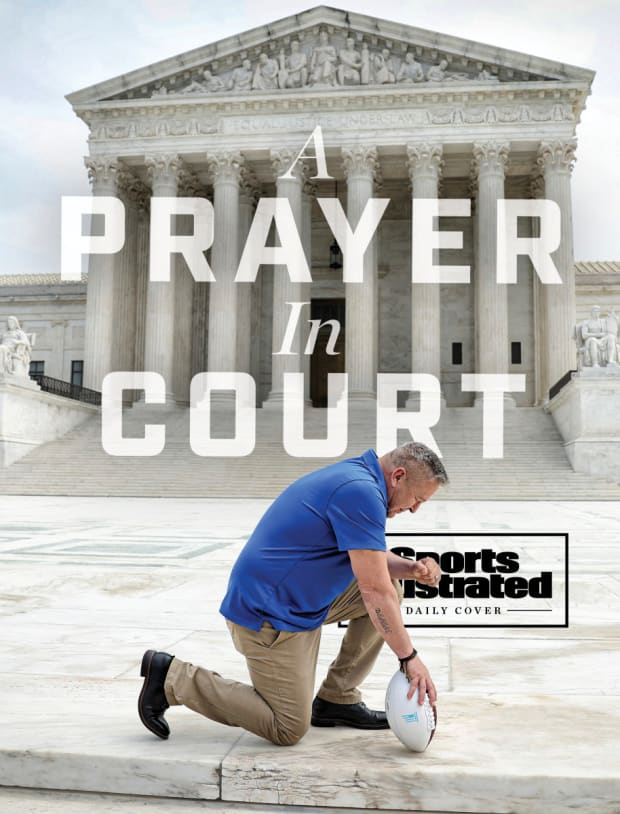

After the game clock hit triple zero, and after the teams shook hands, no one left the stadium. Instead, all eyes trained on Joe Kennedy as he walked onto the field. Once at the 50-yard-line, the Bremerton High School assistant coach bantered with opposing coaches, then gave this oddest of audiences the moment it had gathered for.

He dropped down, knelt and closed his eyes in prayer. But after rising, he noticed he had company. Members of the other team. Fans rushing down from the stands. News crews with cameras ready. Smiling politicians. The beginning of a path to much, much more.

Everything changed—for Kennedy, the district that employed him and two sides that came to eye broader objectives in their feud—in those 15 seconds.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

Kennedy insisted then and maintains now that he didn’t want any attention. That he desired only to pray, by himself, briefly, right there, as he had done after every game for eight seasons until the school told him that fall he had to stop. And that, despite his leadership role overseeing impressionable teenagers, his actions weren’t intended to coerce anyone.

His opponents say his intentions don’t matter, and, if they did, this scene was his creation, anyway. Kennedy had spent those previous six weeks conducting multiple interviews that exacerbated his conflict with the school. Two weeks before the game, he had retained First Liberty, the powerful Christian conservative law firm, in his burgeoning legal battle against the district. And he intensified the spotlight’s glare before kickoff with a pregame Facebook post, announcing a big night upcoming. In signing off, he asked for prayers.

It’s hard to read that sequence as anything other than performative, a plea for the exact kind of attention likely to add sympathetic supporters to his side. His opponents argue he got exactly what he wanted. But Kennedy says “uh-oh” flashed through his mind that night. Here, and in many other places, skeptics describe his framework as convenient, nifty bits of PR spin.

Regardless, the coach makes for an unlikely figurehead in these legal theatrics. He was aimless for most of his 53 years. For decades, he wasn’t religious at all, and he isn’t overtly so now. He never followed football all that closely. And yet, he is now at the center of a seven-year legal conflict that started with that covenant—to pray after every game. That morphed into a controversy, then a circus, then a lawsuit centered on the First Amendment and its clauses. That broadened into a political brawl. That widened into a culture-war cudgel. And that wound through the court system, until case No. 21-418 landed on the docket for the Supreme Court of the United States.

Kennedy’s life is now part of the public domain, an emblem to be viewed, utilized and manipulated for others’ aims. He’s a human embodiment of a country that’s deeply divided; a religious movement that’s surging with momentum, even as organized religion becomes increasingly less popular; and, most of all, a powerful right-wing machine many say is employing a timeless division tactic: us vs. them. All morphed a man’s unremarkable existence into an extraordinary one and imbued Kennedy with elusive, far-reaching purpose. He’s no longer just a man. He’s now a symbol, for what his supporters term “religious freedom.”

To them, he’s a hero, David slaying an anti-faith Goliath. To others, he’s a sledgehammer aimed at a bedrock of democracy: the separation of church and state.

It’s improbable that Joe Kennedy stands here. What’s not improbable at all is that someone would eventually have been placed where Kennedy now stands.

On that long-ago night, whether Kennedy wanted to create a scene or not, he got one. Even then, it’s unlikely he sensed where everything would lead. He did know two things with unwavering certainty: The district had a fight upcoming—and it had picked the wrong opponent. Defiance was his specialty, an ethos and defensive mechanism.

Reporters shouted questions. Supporters clapped and cheered. Security escorted him off the field. To observers, he appeared emboldened. But he says he felt sick, as the full magnitude of his stance started to sink in. At that point, he no longer welcomed the gathering storm. He turned off his cell phone. But not before he typed out another Facebook post sure to foment his growing legion of allies.

“I think I just might have been fired for praying.”

Rachel Laser winces and groans and stiffens in frustration on a Zoom call in early May. As the lead lawyer for Bremerton School District and the president/CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, she’s neither exasperated nor discouraged—not exactly. The better word is “terrified,” because this case, and others like it, have transported her to an alternate universe of disinformation and propaganda—and, in that world, even democracy is in danger.

While reporting this story, Sports Illustrated reviewed more than 1,000 pages of documents related to the lawsuit and met several times—in person, on the phone or via Zoom—with Kennedy and his legal team. SI also conducted more than 15 other interviews, including five with independent scholars or legal experts who hold no vested interest in the outcome. Three considered it, like Laser, as perilous to foundational American ideals, while two hedged, describing that sentiment as “overblown” or “misguided.”

Laser’s wider argument starts with a baseline, for both camps: two sides of a country that stand on opposite ends of a vast and growing and existential divide. Both push for their version of “rights.” Both cling to the same document, the U.S. Constitution. But Laser makes a critical distinction in how they push. One side uses facts, she says. The other, she believes, distorts them. (Four scholars agreed.) She (and three of the scholars) define the latter side as “white Christian nationalists.” They believe America was created by a preeminence of people like themselves and should always have laws in place that reflect America’s origins.

Many of those nationalists, Laser continues (and four scholars agree), live in a country they claim to no longer recognize, and, many of them see an “other” America that now exists in its place. One that elected its first Black president (2008), embraced the end of a white Christian majority (’14), hailed marriage equality (’15) and elected a record number of women to Congress (124 last year).

While its numbers shrank, the Christian conservative base was reinvigorated and emboldened over the past seven years, anyway. That owes mostly to Donald Trump’s presidency, his proposed Muslim ban and anti-immigration stances, his border wall and inciting rhetoric; and his appointments of religious conservatives to the judiciary’s most powerful positions.

The Christian conservative undertaking—described by three Kennedy supporters to SI as “a war”—led to an informal playbook, a strategy that Laser refers to as “jujitsu” and others (including two scholars) describe as “white Christian fragility.” At its core, they argue, is an intentional misdirection built not on facts but fear. Like when religious conservatives claimed that advocates for same-sex marriage aren’t in favor of equal rights but anti-religion. Groups fighting for legitimate equality are framed as wanting to take from Christians. This logic twisting makes the arguments zero-sum and assumes that Christian nationalists have lost their rights—all to maintain a culture-war strategy that hinges on a gross oversimplification of stakes.

“That’s what this case is about,” Laser says. “A movement that is so determined they are not willing to stop. They are willing to destroy our democracy to achieve their ends.”

The movement, according to Laser and three scholars, is backed by a billion-dollar industry that brands its argument not under “Christian nationalism” but the more palatable “religious freedom.” Laser (and three scholars) say that’s part of the disinformation campaign. She also points to briefs filed in support of Kennedy on the SCOTUS docket from organizations that have publicly argued in favor of Muslim travel ban and against voting rights, LGBTQ rights, and to overturn Roe v. Wade. She describes the ledger as a “who’s who of religious extremists in this country.” (Responding to that characterization via email, First Liberty special counsel Jeremy Dys wrote, “I have not heard that. What I know is that we would represent [Kennedy] regardless of his faith.”)

Given the legal precedent, Laser calls the case a “slam dunk” in the district’s favor. She knows it’s not, and that Kennedy is expected to win. She agrees he is a symbol. She even, in some ways, sees him as a sympathetic one. She allows that he might not see the larger picture she is painting—or might not have at first. But whether he sees it no longer matters, because she can’t square this unremarkable man with the dire goals of the larger movement she sees his case folding into.

“This coach is being used as a pawn,” she says.

And his compelling backstory makes him that much more effective.

Kennedy reclines in the backseat of a rented SUV in early April. He’s still trying to reconcile how in the heck he ended up here, three weeks out from his appearance in the Supreme Court. He cannot understand this idea that his story intertwined with that of modern-day America—germane to a specific time, place and schism. He laughs at the larger notions, connections to which he never has subscribed. Pawn? No way. (“If crazy people are saying untruthful things, I would hope they would either stop or people would ignore their lunacy,” Dys wrote to SI via email.)

He’ll make that clear, he promises, through a trip back in time. One he will take on that day in the place where his story and the case both started, roughly 45 years apart: Bremerton, Wash.

He points to Harrison Memorial, the hospital perched on a nearby hill. He was born there and immediately given up by a teenage mother. His adoptive parents believed they couldn’t have children of their own but desired a large family. So they adopted a baby girl through an arrangement with a local Catholic church. And, about one year later, they added Joe.

Despite the religious nature of his placement, Kennedy didn’t recite Bible verses every night. For most of his childhood, he says he “hated” God.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

The SUV parks. Kennedy takes a deep breath. That house, he says, pointing across the street, was where he first grew up, when he didn’t say prayers so much as he needed them. The trouble started there, around age 7. His adoptive parents discovered that not only could they have children, but they could have many and did, birthing five in rapid succession. Only then, Kennedy says, did they tell him he was adopted.

The next six years, through age 13, are a murky mess of memories, a precise retelling lost to time and smoldering rage and a childhood lived without purpose beyond the only thing that mattered: survival. Of him and older sister, Kennedy says his adoptive parents didn’t “need us anymore.” But they didn’t exactly give him up, either. (Sports Illustrated was unable to reach Kennedy’s adoptive parents, or obtain his adoption records, which are sealed.)

They neglected obvious needs like school lunches and clean clothes—details confirmed by his neighbors, the Reeds; Gloria and Hansel to most, “mom and dad” to Kennedy. Hansel says Kennedy’s adoptive parents “treated him like crap, the worst,” like when they locked the front door at night, leaving him with nowhere to sleep.

Kennedy bounced around, shuffling between his adoptive parents, the Reeds, three foster homes and two group homes. He lived briefly with an uncle and made dozens of emergency overnights on couches, in parks, or under outdoor awnings. He first broke into a garage for shelter at age 9.

He admits that he lashed out, that his actions made things worse, that he was “a terrible kid”—even if his wrath was understandable. His elementary school booted him in third grade for truancy and fighting. He went to a Catholic school where the nuns told him they were praying for his soul because he would “never amount to anything” and would “only cause pain” to those he loved. He had hardly tried organized sports when he was banished from his first baseball team for striking someone with a bat.

His beloved neighbors at least had a son of the same age. They became like brothers, and while the Reeds never formally adopted him, they gave Kennedy something more important—his first taste of purpose, which became the high he chased.

“Those people saved my life,” he says.

He wouldn’t see how for years. Especially on another night, when he jimmied the lock to a Catholic church and tried to sleep underneath a pew. All the noises—creaking wood, random chimes, the echoing of his footsteps—spooked him. At that moment, Kennedy says he didn’t just hate God; he also feared Him.

Here he was, still a boy, virtually alone, abandoned and cast aside. His anger was really sadness. He didn’t belong anywhere, to anything or anyone.

What’s the big deal? Kennedy often wonders. Football, as he views it, always twinned perfectly with faith. Think Tim Tebow affixing Bible verses to his eye black … “Hail Mary” passes … players who thank God in news conferences … locker-room Bible study … postgame prayer circles … team chaplains … the Touchdown Jesus statue at Notre Dame. Faith is everywhere in football, the relationship between both so long and deep that there’s a section detailing their intersection at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Kennedy believes the two belong together, at an intrinsic level, both as American as the stars-and-stripes. He isn’t alone in that conviction, as evidenced by the NFL Hall of Famers (like Steve Largent, Joe DeLamielleure and Darrell Green) and current players (like Kirk Cousins and Nick Foles) who submitted legal briefs on his behalf. But while the outward faith-and-football messaging resonates deeply with Christian conservatives, it’s not actually what Kennedy and his legal team, First Liberty, are arguing in court.

While they often frame the case as a simple but egregious violation of an American citizen’s First Amendment rights, legally their position—and the district’s counter—center on divergent answers to the same question. Was Kennedy’s covenant simply a private expression of his religious beliefs? Or was it coercive—a public school employee, on district property, at a public event, while working in an official capacity, in a leadership role overseeing teenagers—not private at all?

Kennedy’s lawyers style his ritual as short and solitary, noting he never intended to pull anyone into it, let alone his players. They maintain that his prayers never lasted long. They insist that, once those prayers started attracting attention and the school’s principal told Kennedy to stop, he did. And they disagree with the district’s contention that it provided reasonable alternative accommodations—that he could pray by himself in the press box, which had glass windows in view of the stands; or once the stadium had emptied; or after taking the long walk to the school, down to the bottom level and into the custodian’s closet. First Liberty argues that those options were reprimands masked as compromises, choices made intentionally difficult to force him to stop praying.

First Liberty, as the nation’s largest nonprofit legal organization with the stated exclusive aim of “defending religious liberty,” is no stranger to such arguments. It has represented Muslims who weren’t allowed to put a cemetery on their purchased property and Jews who couldn’t partake in a customary atonement ritual by slaughtering a chicken on the eve of Yom Kippur.

While Kennedy retained First Liberty before that October game in 2015, his lawyers remain adamant that Kennedy’s decision to pray in defiance of the school district that night was his own. “Coach makes his own decisions,” Dys wrote in an email to SI, “as anyone can tell from meeting with him for more than a few minutes. And as his lawyers we follow his instructions.” Dys adds that the goal was to resolve the case in ’15 and allow Kennedy to return to the team as soon as possible. For Kennedy’s case, First Liberty added Paul Clement, the former U.S. Solicitor General and an ace Supreme Court litigator.

All work for Kennedy pro bono. But don’t mistake a lack of bills for altruism. As with the promotional video they released that sells Kennedy as an everyman confronting the cruel establishment of religious suppression through his Bible and guts alone, it’s all part of the story they want to tell and sell.

In what its opponents describe as ongoing attempts to redefine church and state, First Liberty has argued that attempts to stifle teaching creationism and sanctioned prayer in schools represent hostility to religion. Those opponents see the Kennedy case as the likely next step in what they describe as an “erosion” of the separation, their argument backed by other recent rulings: that “God” can remain in the Pledge of Allegiance, that the federal government can give money to faith-based schools, and that religious groups can discriminate based on their beliefs when hiring.

The effect on the human inside this crucible is both massive—years out of coaching; a cross-country move; a near divorce—and incidental. Politicians who likely couldn’t pick Kennedy, the man, out of a lineup, posture and take “moral” stands to further their careers. The Kennedy supporters SI spoke with highlighted their religious convictions, tying their aims to the same principle: that nothing and no one should come between them and their faith. Kennedy, the symbol, is fighting for them.

Kennedy may not be handing over cash, but there is a base to rally and resources to be raised through donations to the cause. Whenever the coach makes his frequent appearances with various types of news outlets, including several hits on Fox News or with Glenn Beck, the publicity barrage can seem designed to ramp up his case’s notoriety, stoking both anger and donations.

Laser’s organization, and others like it, have their own agendas, too, not to mention organizational similarities. But she believes that the context of how Kennedy fits into the larger movement shows the evolution of the stakes. The argument isn’t whether faith belongs in football. It’s only somewhat about private vs. public prayer. For Laser and the four scholars who subscribe to her wider arguments, it’s really about whether church and state should be separated—and where that line of separation should be drawn. Or redrawn. Or removed.

Kennedy’s search for purpose continued in his teens, after his adoptive parents returned to his life only to trick him with a short vacation to nearby Port Angeles. They no longer lived in Bremerton, but they still held legal agency over him, due, he thinks, to an overwhelmed foster care system. At the end of the weekend, they revealed the true purpose of their jaunt. He was heading to the Flying H Ranch in central Washington. He didn’t have a choice. He would be “locked up” there, at a Christian home for troubled youth, for at least six months.

Kennedy treated the staff there the same way he dealt with anyone in positions of authority—as enemies unworthy of trust. The tougher ones would pick him up by the neck and slam him against the wall or throw him onto a pool table. (Richard Wagner, the current administrator at Flying H, was complimentary of Kennedy but said he is “unaware of any such actions.”) The more empathetic ones dispensed hugs and Bible verses, trying to find commonality in humanity.

One afternoon, a mild-mannered counselor who performed repairs around the ranch asked Kennedy to help him lay down tile in a bathroom. Kennedy stared at Terry Fike—who confirmed Kennedy’s account of his time there – and started an argument about forced labor, I hate it here, life’s unfair. Fike listened, attuned to Kennedy’s lone solution to any problem. “Always a fight response,” Fike says. “He didn’t have a flight one.”

Fike waited for Kennedy to calm down, then softly suggested he try religion. “You’ve been fighting this system forever,” he said. “It hasn’t worked. What are you waiting for?”

Kennedy was putting in tile below a toilet seat, his face inches from the bowl. The juxtaposition of gentle query and lingering smell combined for an unexpected revelation. I’ll try on God, Kennedy thought, and see how it fits. He began dabbling in scripture, Bible study, service. He was eventually released. He prayed his new purpose would help keep him on track.

It didn’t stick.

His search began anew. He found it back in Bremerton, through self-sufficiency, after returning to finish high school. He lived on his own, at age 15, working nights at a restaurant. He moved into a tiny spot, maybe 550 total square feet, in a sad collection of duplexes. Rent cost between $200 and $300 a month. He owned only a few clothes and a hot plate rendered useless because he couldn’t afford electricity. He augmented his income with “illegal stuff on the side” and hustled old-timers at a pool hall for money to buy cigarettes. He didn’t have cable or electricity, but he had a home, Apartment No. 7, and it was his.

He graduated in January 1988, the district confirmed. He posits that his grade point average might have been the lowest ever recorded in school history (his estimate: 0.33). He could do anything, Kennedy says, and he would refuse to give anyone else control over his life.

That didn’t stick, either.

Instead, Kennedy gave up all control, following the Reeds’ son into the Marines. He reported to boot camp at age 18 and served for the next 18 years, rising to the rank of gunnery sergeant, channeling his anger at new (and very real) enemies he encountered on new (and very real) battlefields. His faith vanished. He had a new purpose; he was a fighter, and he no longer needed Him.

Shortly before retiring from the military, Kennedy called his childhood flame. He had first spied Denise brushing bangs out of her eyes at age 9 and rather than introduce himself, he proposed marriage. Their relationship evolved from “you’re creepy” to friends to childhood sweethearts, and even as Kennedy went all over the world, they kept in touch. Both married and had children of their own (one for Kennedy, three for Denise). And, by early 2005, they lived close enough to reconvene. Dinner led to another round of dating, and Kennedy helped untangle her from a bad marriage. But the scars it left ran deep.

They moved immediately back to Bremerton, before marrying in May 2005 at the local courthouse. They blended families. She started at the district as a secretary in human resources. He found work, odd jobs mostly, at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. But his job, all the sweeping and mopping and chipping paint, did not fulfill Kennedy. And off he went, hunting for purpose once more.

He would find it in two places—religion and football—and soon uncover the critical notion that would lead all the way to the Supreme Court: a little faith went a long way.

With legal arguments forever broadening, the back-and-forth of case 21-418 sprawls endlessly, even for the scholars interviewed by SI. Few points were met with universal agreement. Two bought Laser’s argument in its entirety. Those two (Group 1) didn’t want to be named in this story, fearing retribution from Kennedy supporters. Two others (Group 2) endorsed most of her points, but not all. The last scholar (his own Group 3) found both the tenor of the arguments and the tie to the large movement “unfair” to Christian nationalists.

Consider Laurence Tribe, the cofounder of the American Constitution Society and a Harvard professor, a member of Group 2. He believes that religion should “never be discriminated against, dumped into the gutter, or squeezed out” of society. But he also sides with the legal history when he notes that “our system works best, and people are (most free), when church and state are kept as far apart as possible.”

“If it’s elevated above everything else,” Tribe adds, “then people who don’t share the dominant religion are made to feel like outsiders—and that contributes to civil wars among religious lines that have plagued places like Europe for centuries.”

Another constitutional law scholar at Harvard, a self-described atheist named Michael Klarman, draws a distinction between the larger movement and this case. He’s Group 3. From partisan gerrymandering to invalidating sections of the Voting Rights Act to defending the Jan. 6 insurrection, he describes the larger threat from the conservative movement to democracy as “very real.” But with church and state, he says, “Questions of where to draw the line are genuinely hard, and shifting the line a bit in one direction or another is not [part of that threat].”

The real question upon which the case rests, he argues, is: When does private prayer become coercive? First Liberty, he believes, has a plausible argument to make there.

Klarman also finds Laser’s argument as problematic as to how she frames her opposition. “Is Americans United for Separation of Church and State not a machine built on money and privilege?” he asks. “It’s Politics 101 to scare your supporters into believing your adversaries are demons, out to wreak much more havoc than the present incident suggests.” He clarifies that he’s not saying she or the scholars are wrong. But he believes they cannot make such lofty and alarming connections with confidence. Though, he adds, “I acknowledge I could be wrong.”

Tribe agrees, in part—that Kennedy v. Bremerton will not mark the end of a separated church and state. But he does maintain it’s possible that the court will move, through Kennedy, in that direction, and he predicts—as all the scholars did—that the coach will prevail. “Like when [the U.S. Supreme Court] overrules Roe v. Wade, it will be giving a victory to a long-running campaign by Christian fundamentalists who are imposing their view of human life on the rest of society,” Tribe says. “That’s dangerous. I do think it’s a slippery slope.”

Early into their marriage, Denise went to church every Sunday. Her husband did not, despite weekly invitations, until the kids whined about his absences. He suffered through sermons, arms folded, eyes rolling, after that, while growing increasingly alarmed at the state of their marriage.

This leads to another story, from late 2007 or early ’08, that Kennedy expects many will find hard to believe. One Sunday, while “I Surrender” by Hillsong Worship played, he felt a sudden rush. He can’t explain the force that compelled him forward, toward the altar, where he dropped to his knees and sobbed. He proposed a holy trade that day: If God helped heal them, he would walk in faith for the remainder of his days. When he opened his eyes, there she was, his bride, sitting right beside him with her arms outstretched and those beautiful brown eyes wet with her own tears.

God, it seemed, had agreed to his terms.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

Kennedy had also taken up running around then, both to stay active and in part because the darkest memories from battle—dying comrades, clips emptied, devastation wrought—still lingered. He often wore Bremerton Knights gear as he jogged through the streets near the high school, grinding through the turmoil.

On one run in 2007, a man stopped him near the football stadium and introduced himself as athletic director George Duarte. After some small talk, he explained that Bremerton needed coaches. Perhaps Kennedy might want to join the staff part time? Duarte persisted for almost a year, then pushed a real offer.

That night, Kennedy vacillated at the dinner table, hoping his blended family could steer him toward clarity. He worried about upsetting their delicate home balance. But to his surprise, their unconditional support came with questions that made him reconsider. Did he not want to atone for past sins? Wasn’t this part-time gig actually perfect?

Later that night, when he couldn’t sleep, Kennedy flipped through the offerings on late-night television. He came across a movie, Facing the Giants, about a football coach at a Christian school who overcomes a mob of parents intent on replacing him by leading his team to a string of victories. The coach did this not with any intricate football knowledge, but by inspiring his players through faith. Kennedy fixated on one detail: The protagonist praised God after every game.

After this sign from above he decided to “plagiarize” the film’s protagonist, specifically the prayer. God, I’m going to give you the glory after every game, win or lose. “It was,” Kennedy says, “my covenant” with Him.

Never mind the countless hours for a “part-time” gig, perpetual headaches and meager salary ($4,500 a season). He could build discipline, shape leaders and propel players in a downtrodden program toward “peak” performance. After finally uncovering his true purpose, he could help kids like him.

And, yes, he knelt in prayer at midfield after every game.

The district’s lawyers anchor their argument in legal precedents, the decades of rulings that clearly prohibit state-sponsored prayer in public schools. Like in Engel v. Vitale (1962), in which SCOTUS ruled that even “brief-and-general prayer” authorized by a school marked a violation of the separation. Or, more recently in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000), when SCOTUS affirmed that students at a high school in New Mexico could not lead organized prayer at football games.

Kennedy could have drawn a connection from his time at Flying H. The ranch still exists, but ended its partnership with Washington state due to conflicts over faith-based curriculum. Officials chose to alter their structure, becoming a private entity; Kennedy chose to sue. But the basic elements—public funding/government entity/religion—are the same.

What’s different now? The landscape. Tribe says Supreme Court decisions on church and state made in the 1960s would have been rendered differently today. Starting with the Reagan Administration, he watched conservatives undertake a “systematic packing of courts with judges who don’t really believe in the separation.

“And it has accelerated now, to the point where all three of the [Supreme Court] Trump appointees are committed to tearing down that wall,” he continues. “Although they wouldn’t put it that way, it’s crumbling faster than ever before.”

Kennedy supporters point out more recent judgments in that vein that skew toward allowing more freedom for one group at the expense of others. One ruled in favor of churches that opposed COVID-19 restrictions, another for a Catholic adoption agency that eliminated same-sex couples from foster care consideration.

Lower courts, bound by precedent, ruled against Kennedy. They often used atypically strong language—for example, the term “deceitful narrative” is used in reference to Kennedy’s counsel’s assertion of his “silent, private prayer”—to dismantle his arguments. Had the case moved to the Supreme Court level earlier, it’s likely, Klarman says, he would have lost, because Justice Anthony M. Kennedy represented the Supreme Court’s swing vote. He had aligned against his conservative brethren in similar cases, like Santa Fe. Trump had already nominated Justice Neil M. Gorsuch in 2017, and, when Justice Kennedy retired the next year, Trump tabbed Justice Brett Kavanaugh to replace him. “That’s the key development here,” Klarman says.

Joe Kennedy’s case was elevated to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which denied one of his last available motions. And, in 2019, SCOTUS declined to review that decision, marking what seemed like a dead end. But in reality, it provided the possibility of a future review.

In this particular place, at that specific moment in time, few locals seemed to care about the praying football coach at first. Bremerton is only about an hour by car or ferry from liberal Seattle, but proximity does not equate to similar. It’s home to about 40,000 people, a U.S. naval base, and, by one count, 100 churches—or one for roughly every 400 residents. There, for most of eight seasons, Kennedy says, “We never had a problem.”

In those years, he ran the JV team and helped with the varsity, while feeding and clothing anyone who needed it. He repaired worn-out cleats with duct tape and gave Gatorade to players who worked hard, while raising cash for camping trips and new equipment. A team that won two games combined before his arrival went 9–2 and won the district title in his fifth season. There it was: purpose, powered by a new, super-charged engine: faith.

Still, as the years went by, more and more residents began to notice Kennedy’s dedication to his covenant. Players started asking whether they could join. Kennedy allowed it. “Lord,” he would say, “I want to lift these guys up for the battle they just fought. I just love ’em and appreciate being a part of their lives.” When a captain asked whether he could invite the other team, Kennedy again said yes.

He also deepened how his faith informed his coaching, leading prayers in the locker room and giving motivational speeches built around stories from the Bible. (Klarman calls these actions “obviously impermissible in a way that his own prayer wasn’t.”) Regardless, Kennedy did not consider how his views might be coercive, even inadvertently, when delivered in that setting.

Per Kennedy’s recollection, two families did raise issues with him directly. One parent told Kennedy he didn’t “want my kid involved with any of this.” Kennedy says he promised to uphold the father’s wishes. Another player addressed Kennedy directly. Kennedy says he lauded the athlete for his conviction. In both cases, the coach considered his response sufficient. But he also placed the onus of broaching an uncomfortable subject on the parents or their teenagers, leaving others to wrestle with just how separate church and state should be.

After the “prayer that got me fired,” the district placed him on paid administrative leave. When it came time to renew his contract for the next season, he didn’t reapply. After the childhood of turbulence, the Marines and all his progress, he chose—or, he argues, the district forced him to choose—to upend everything again. He says he considered obvious factors. He was suing the district. Denise, by that point, ran the HR department. Both reasonably expected that Bremerton would not renew his contract. But he wasn’t fired. He was fighting.

To his legal opposition, Kennedy’s covenant, however intended, was coercive, delivering a powerful message to teenagers who wanted to play and coveted their coaches’ approval. Some might have participated to curry favor or join “us” rather than “them.” One brief in the SCOTUS docket is from psychologists who argue there’s a fragility to adolescent minds.

Laser, the district’s lead lawyer, points to one moment from the SCOTUS hearing, when Kavanaugh reminded the courtroom of his time in coaching and asked Clement about coercion. “What about the player who thinks, if I don’t participate in this, I won’t start next week?” Kavanaugh wondered. “Or the player who thinks, if I do participate in this, I will start next week?” Clement redirected, saying the coach in that hypothetical would be wrong, coercive, doing what Kennedy had not done. Kavanaugh then raised Laser’s point for her. How could anyone tell the difference, if coercion isn’t obvious and yet conformity is expected?

Kennedy backers point to another SCOTUS case, Lee v. Weisman (1992), where the justices determined that clergy could not give official prayers at ceremonies like for graduation. But in the dissenting opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia made a distinction that could prove pivotal for the Kennedy case. Only “coercion backed by the threat of penalty” should count, he wrote, not “psychological.”

The district’s arguments revealed examples of the latter, through one Bremerton player and the parent of another athlete. The player said he refused to bow his head out of respect for his own beliefs, then was “persecuted” for not fully conforming. From the brief: “The coaches were unfriendly towards him and only tolerated [him] because [he] was a good player and had the respect of [his] team.” The backlash, he said, still haunts him. Same went for district employees who received death threats from religious supporters.

Tribe can understand why Kennedy’s legal team maintains he wasn’t being formally coercive. He wasn’t speaking for the school or praying at an official graduation ceremony, per se. But Tribe also views the continued erosion of separation as harmful to religious groups; when there’s a dominant faith, he argues, it’s not just other religions squeezed to the margins.

He points to other citizens, closer to the middle, with less extreme viewpoints, who might argue that society is falling apart and fundamental Christian principles are good for society and what’s the big deal? But, Tribe says, “In the very long run, that’s going to mean much more entanglement between church and state. That’s going to be dangerous to an ideal society where nobody feels that their religion or lack of it makes them second-class citizens.”

In declining to review Kennedy’s case in 2019, the conservative SCOTUS members expressed interest in the broader legal issues it raised. Samuel A. Alito Jr., one of the most conservative members, highlighted a specific concern. He asked whether the 9th Circuit meant that all coaches must refrain from any “manifestation of religious faith,” even when “they’re not on duty” and described the lower court’s understanding of First Amendment clauses as “troubling.”

When Trump appointed another conservative judge, Amy Coney Barrett, to the Supreme Court in October 2020, the conservatives added another member to their team. More rulings in Kennedy followed, as did more appeals. But in Sept. 2021, as foreshadowed, SCOTUS put Kennedy on its docket—only with an even larger conservative majority to weigh in.

To Tribe and three of the other scholars, that’s not a good thing. He predicts SCOTUS will rule, 6–3, in Kennedy’s favor. And if that happens, he says, America “will look much more authoritarian.” He highlights Roe v. Wade, as an example, pointing out that those in favor of overruling the decision are a clear minority (around 33% according to a recent Gallup poll). “Because of gerrymandering, they’re exercising the majority of the power, and they have a court with true believers,” he says. “The country is rapidly heading into a less-and-less situation. It’s less democratic and less inclusive.

“And, in the long run, that will make us all less free.”

Kennedy strides down East Capitol Street, clad in a blue polo shirt and khakis, sunglasses hiding the determination in his eyes. He spins through the plaza, past the fountains and the marble candelabras and the bronze flagpole bases crested with symbols, everything designed to convey importance and significance, the heft of history.

None of this is lost on him.

The former assistant football coach never expected he’d be here. But he is here, gaining purpose with each step, up the stairs and through the pair of bronze doors that weigh 13 tons combined. He’s almost floating now, down a long corridor and into the Great Hall, past rows of marble columns, toward the chamber where nine justices shape American history inside a small-but-dignified room with 44-foot-tall ceilings. The Supreme Court of the United States.

It’s April 25, Kennedy’s “final chance,” the precise moment when the man and the symbol become impossible to separate anymore. Kennedy sits down in the chamber. Every other eye in the courtroom turns his way. He’s no longer nervous. He’s ready. In the fight he couldn’t let go of, the bell sounds for the final round.

The arguments last for almost two hours. First Liberty covers the proceedings like a football game, with two reporters on-site offering observations.

His new status, as a symbol to tens of millions of Americans who view him as their champion carries both a real emotional connection to why he’s so entrenched and a deeper purpose than he ever had before. He says he only wants to coach at Bremerton again. But he also tells SI that he can’t “lose and then there’s millions of people that are going to be screwed for the next 50 years.”

Of course, in the unlikely event a court packed with conservative judges rules against him, those “millions of people,” affiliated with a religion that holds immense wealth and power, would be almost completely unaffected. If/when SCOTUS rules for him, it will add steam to a movement that threatens to force religious views—no matter how unpopular or ethically dubious—and alter the lives of those who don’t practice that specific faith.

Does Kennedy know? Does he care? Or did he evolve to embrace playing the “hero,” and having this large of a purpose? Maybe the political operatives who stood with him found the perfect mark, a man in search of a calling, a grand stage. They gave him the biggest theater imaginable—the Supreme Court—to further their agenda, while groups fighting for their own aims joined in. After all, football never drove Kennedy, nor did faith, until more recently. But this saga of faith-and-football now reads like Kennedy’s own Christian football movie. He’s the hero. He wins, and for everyone on his side.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

As he leaves the nation’s highest court that day, Kennedy doesn’t seem to notice the five clergy members from greater Bremerton in attendance. They’re half of a group that filed a brief on the docket—but not in support of him. After the arguments have ended, they explain why on the courthouse steps. They also hail from his hometown. They also care deeply about religious freedom. But they must consider all faiths and all people, period, and they believe that this freedom stems from protecting the separation of church and state.

Their stance opposite of Kennedy even includes a Bible verse intended to debunk his argument. It’s Matthew 6:5: “When you pray, don’t be like the hypocrites who love to pray publicly on street corners and in the synagogues where everyone can see them. I tell you the truth, that is all the reward they will ever get.”

That same afternoon, while the clergy make their case, Kennedy walks past them, down the steps and toward the waiting television cameras. Then he kneels, his right hand holding a football, and prays once more to a waiting and eager audience. As he bends, he can’t help but grin.