Environments across the planet are changing dramatically in response to human population growth and climate change. Some scientists even say human activity has pushed Earth into a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.

Amid this rapid transformation some special places, protected by fortuitous geography and geology, change so slowly they preserve evidence of Earth’s past over unfathomable timescales.

One such place is the flat, dry expanse of the Nullarbor Plain in southern Australia, where traces still remain of events millions of years in the past. Using high-resolution satellite imaging we have begun to map out some of these traces.

In new research published today in Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, we report the discovery of an enigmatic “bullseye” structure more than a kilometre across. We believe it is the remains of an ancient reef, created by microbes some 14 million years ago when the Nullarbor was at the bottom of the ocean.

No trees, no water, but not boring

Named the Nullarbor Plain (meaning “treeless”) during colonisation, and Oondiri (meaning “waterless”) by some of the First Nations people of the area, the region is notoriously dry, flat and barren. The exceptional overall flatness of the plain (the average slope is much, much less than 1°) is one of the first indicators of the region’s stability.

The rocks beneath the Nullarbor Plain are made of limestone that originally formed in shallow marine seagrass meadows. Such rocks can dissolve in weakly acidic rain and groundwater.

Due in part to its dryness, the region has not been intensively dissolved, or eroded by rivers or glaciers in the millions of years since it emerged from the ocean. This is in stark contrast to the classic ruggedness of much younger tropical landscapes (such as the volcanic Hawaiian islands), which are far wetter and more geologically active.

The plain covers some 200,000 km² and, like the curvature of the Earth, landscape features on the Nullarbor Plain are almost imperceptible to the human eye. Despite this subtlety, the area is not as featureless as you might think.

Careful scientific study and high-resolution satellite data are increasingly revealing the secrets of the Nullarbor Plain’s past.

Mummified marsupials and ancient dunes

Isolated caves do punctuate the Nullarbor Plain. Within their dry chambers, remarkably preserved fossils yield glimpses of Australia’s extinct animals that would rival the most wondrous zoo menagerie.

Mummified thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) remains and complete thylacoleo (marsupial lion) skeletons from thousands of years ago capture striking snapshots of changing ecosystems.

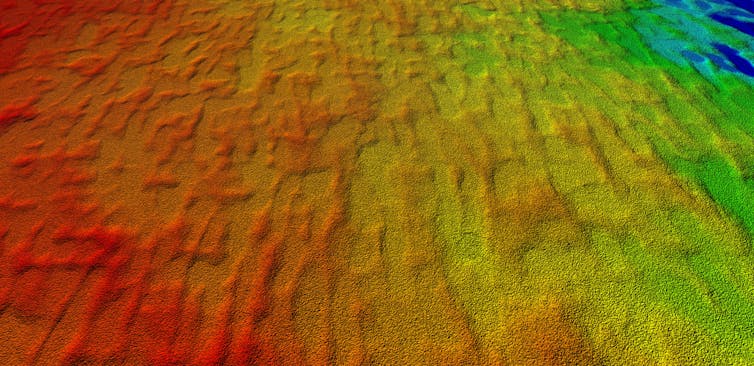

Older still are gentle linear ridges that cross the Nullarbor Plain. Recently, we showed these ridges are relics of a long-vanished landscape. Ancient sand dunes controlled the gentle dissolution of the underlying limestone to leave a subtle imprint of windblown patterns from millions of years ago.

The bullseye

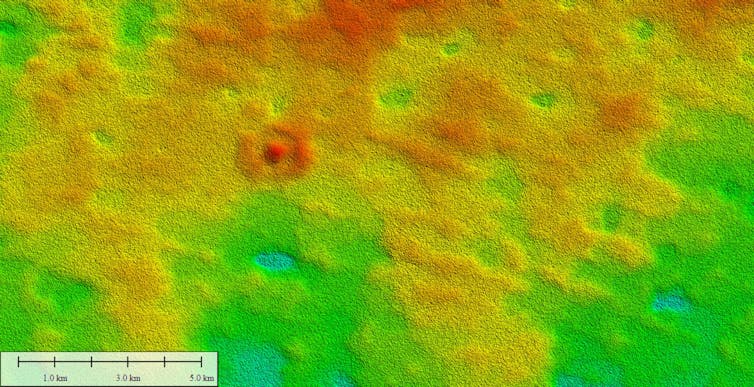

For our most recent work, we used landscape data from the TanDEM-X Digital Elevation Model produced by the German Aerospace Centre, which has a resolution of around 12 metres.

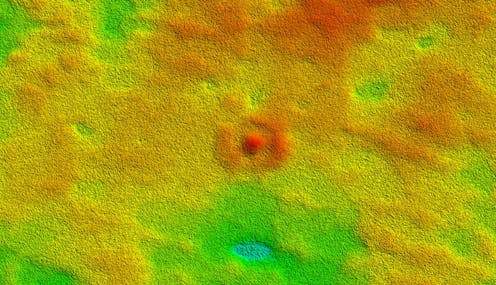

Studying these images of the Nullarbor revealed a previously unnoticed “bullseye” feature: a ring-shaped hill with a central dome, just over a kilometre wide and only a few metres high.

Initially, we thought we had found the first meteorite impact crater to be discovered on the Nullarbor Plain. The area is famous for meteorites that can help us understand the history of our solar system, but to date no definitive craters caused by meteorites have been found.

However, when we took a closer look at the bullseye we saw none of the chemical or high-pressure indicators of an impact.

We uncovered the real explanation for the bullseye after cutting and polishing samples of rock thin enough to let light shine through, and inspecting them under a microscope. Unlike the limestone seen at hundreds of other sites across the plain, here we saw evidence for tiny microbial organisms holding the sediment together.

Supported by similar “doughnut” structures formed by algae on the Great Barrier Reef, we interpreted the bullseye as an ancient isolated “reef”. This biogenic mound formed on the seabed long ago but degraded so slowly after the land was lifted above the waves that it is still recognisable roughly 14 million years later.

How understanding the past can help the future

Our findings add to increasing recognition of the region as an exceptional archive of environmental change that we must better understand and protect.

The emergence of the Nullarbor Plain has been an important driver of the evolution of plants and animals. Ancient fossils and even DNA preserved due to the stable conditions will help us more accurately reconstruct its vanished ecosystems.

More complete understanding of how landscapes and ecosystems were transformed in the past will in turn help us conserve the animals, plants and environments we have today, and minimise the negative impacts of future anthropogenic climatic change.

Milo Barham receives funding from the Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia, as well as Iluka Resources Ltd. for investigating mineral sands, including on the margins of the Nullarbor Plain.

Dr. Matej Lipar receives funding from Slovenian Research Agency, Australian Speleological Federation Karst Conservation Fund, and German Aerospace Centre TandemX.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.