I was reading Noongar author Claire G. Coleman’s third novel, Enclave, a few days after the US Supreme Court overturned the Roe v Wade judgement, a political victory for a conservative project many years in the making.

As Michael Bradley argues in his recent article in Crikey, those driving this project “want to live in the America of their small imaginations: white, straight, patriarchal, Christian and mean”.

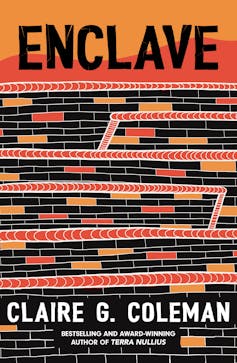

Review: Enclave – Claire G. Coleman (Hachette)

Such small imaginations also inhabit the world of Enclave. Divided into two parts, the novel opens in a dystopian society just enough like our own to be disconcerting.

The third-person narrative is told from the perspective of Christine, who is soon to turn 21. She has recently completed her undergraduate degree and is about to enrol in a Masters of Pure Mathematics. She has grown up in a walled town ruled by a Chairman and controlled by an Agency full of identity-less men in charcoal suits, backed up by security forces. People are led to believe that the widespread camera surveillance and armies of drones keep them safe.

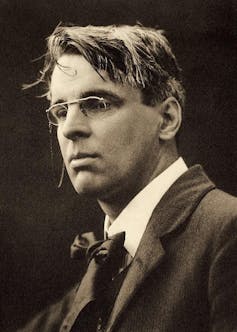

The world is hotter than our own, so everyone lives indoors in temperature-controlled environments. Opening a window in your own home is enough to alert the security forces. Light does not illuminate – it sneaks up, heats up, blinds and glares. It is violent and ugly bright, not unlike the “blank and pitiless” gaze from W.B. Yeats’ poem The Second Coming.

Christine lives a life of seemingly immense privilege. Servants are bussed in from outside the wall each day to serve her every whim. The algorithms of the Enclave’s social network anticipate and manufacture desires that are met before Christine is even aware she has them.

The Safetynet’s news service feeds residents a constant stream of images of the terror, violence and chaos outside the wall, from which the Agency is protecting them.

The people of the Enclave live in uncannily similar homes that all seem new – even the faux old buildings of the University. They present perfectly manicured and curated lives on Safetynet socials. The town is nominally Christian, but no one goes to church.

Christine is just starting to wake up to the reality of her situation. Her family is cold and loveless. Her father is a callous and unfeeling patriarch who works for the Fund, which controls the finances of the town. He wants Christine to do the same, at least until she gets married.

Her mother drinks herself numb during endless long lunches with empty women who all share the same cosmetic surgeon. She exhorts her daughter to do the same, which is both menacing and hangover-inducing.

Christine’s brother Brandon, a clone of her father, is a business student preparing to work for the Fund. He is, as she suggests, a real dick.

Christine is also mourning the mysterious disappearance of her best friend Jack who, in a dig at the handful of controversially well-funded programs in the Australian university system, studied in the Western Civilisation Studies department. She is awaiting a message from him through a secret channel. It never arrives.

Read more: The concept of 'Western civilisation' is past its use-by date in university humanities departments

Becoming illegal

Life in the Enclave is deeply oppressive, not to mention boring. Questioning the status quo is not tolerated. The lonely, loveless and listless descriptions of Christine’s world are enervating.

Although she is meant to be rather smart, Christine has a remarkable lack of curiosity – an effect, one supposes, of the world in which she is raised. But for the first time in her life, she is starting to notice that all of her servants are brown-skinned or darker. Though they move around her home silently, catering to her every need, she doesn’t know any of their names.

Things come to a head when she sees for the first time that one female servant in particular is breathtakingly beautiful. She feels desires that she wasn’t aware were even possible, and kisses her. They are caught on one of the many surveillance cameras. Her family is appalled, not only because Christine is attracted to a woman, but to a dark-skinned woman. According to her father, this makes her a “dyke, race traitor, bitch”. (I was more concerned about the power dynamics between master and servant.)

Christine is cut off from everything – money, accommodation, communication – and taken into custody. She thus learns that Safetown, the name of her walled Enclave, is actually a private facility, so being without support is trespass. She is, in effect, illegal.

Safetown, it transpires, is one of several organisations that established walled enclaves made possible by earlier government policies and laws. It is an economic and socio-political enclave started by extremely wealthy people, to produce and sustain a homogenous society.

Christine is cast into the world outside Safetown: a hellish liminal zone where sunburned white exiles, dressed in rags and living off soup kitchens, slowly go mad. In this violent and dangerous place, people survive by trapping rats and pigeons with discarded wire. This wasteland is littered with corpses, evidence of prior occupation of the land on which Safetown was built.

Read more: Witchcraft and fascism collide in Jane Rawson's imaginative new novel

Utopian and dystopian

Coleman’s vision is both utopian and dystopian. The world of the Enclave is a dystopia created in an attempt to realise an exclusive utopian vision: a homogenous world of straight white people served by a coloured underclass. In Safetown, everyone believes themselves to be protected from the chaos and violence outside the wall.

Part two reveals Safetown as the walled dystopia the reader already knows it to be. And it offers a revised postcolonial and queer utopia – a place of radical inclusivity, in the form of a more technologically advanced version of Melbourne.

Buildings are covered in plants to combat climate change. Trains are free to keep cars off the road. There is a universal income. Education is free and world-class. There is no surveillance or drones. Food is multicultural and always delicious; the coffee uniformly good (in that sense, not too different from Melbourne today):

It was like a fever dream of a civic heaven, all light and beauty and people in connection with the natural world, which appeared to be invited into all human spaces […] And everywhere there were people, men, women, people she could not determine either way, every spectrum of skin colour from darker than Sienna to lighter than her.

Like all literary utopias, Coleman’s idealised city reminds us that change is possible if we can imagine an alternative vision that makes change worth fighting and hoping for. But the novel also falls prey to the dangers of all utopias with its ideological certainty, its lack of nuance, the totality of its vision, and its dehumanisation of those who don’t share it.

Surely, I’m not the only reader who is suspicious of a utopia in which everyone is beautiful. And a place where everyone is happy all the time has its own sinister and coercive feel, flying in the face of the human condition as it does.

Having said that, Enclave is a novel that inclines towards hope. It touches on many of the issues of our own world – the ecological crisis, the scourge of racism, Australia’s treatment of refugees, greed and the manufacture of algorithm-driven desires, our acceptance of widespread digital surveillance and stolen attention, and the refusal to adequately acknowledge prior occupation and dispossession. It also reminds us of the dangers of the othering politics of fear.

Enclave’s epigraph and some of its section titles are taken from Yeats’ The Second Coming, which describes a strange alternative to the prophesised return of Jesus. The poem opens in a world spiralling into chaos where

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The Second Coming proposes a catastrophic and apocalyptic vision for a world on the brink of self-destruction that seems all too apt for the present moment. Coleman’s novel offers us an alternative: a world in which people, in meeting the demands of the present with curiosity, courage and conviction, can bring about a more just and inclusive future.

Maggie Nolan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.