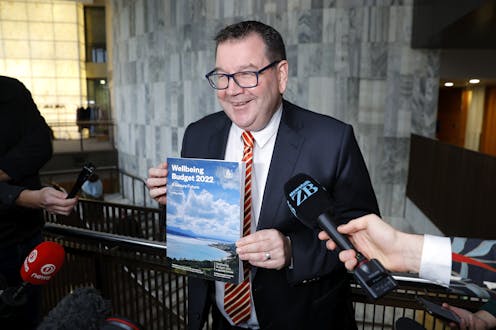

One way to make sense of Finance Minister Grant Robertson’s fifth budget speech was to see it as a political performance working on different levels.

First, Labour needs this budget to do an immediate job – address concern with the cost of living. Following two years of pandemic-dominated politics, Robertson had to tell a compelling story about his plans for tackling mounting fuel, food and other prices.

Reminding people that some of this is beyond the government’s control is not a winning strategy. Handing out something tangible was imperative today – hence a NZ$1 billion cost-of-living package, including a one-off $350 cash payment for some 2.1 million low- and middle-income earners, and extended public transport subsidies and fuel excise cuts.

But the government also wants a reset in its head-to-head with a resurgent National Party. Many voters have moved on from the pre-Omicron phases of the pandemic. And with a genuine contest looming at next year’s election, Labour and the Greens will be hoping today’s announcements serve as a political circuit-breaker.

Some of the big-ticket items – chiefly the health reforms and Emissions Reduction Plan – speak to the longer term. We can imagine the government will be closely watching the Australian federal election this weekend to see how much climate policy influences voters’ choices.

Finally, there may also be something deeper going on. As reaction to today’s budget rolls in, we’ll get a sense of New Zealanders’ ongoing appetite for a more active and engaged state. Here and internationally, the pandemic years have represented a break with small state orthodoxy.

And while Robertson reassured voters and markets that this is a prudent, sustainable budget (many governments would walk over broken political glass for a projected surplus in 2025), the National and ACT parties will seek to portray Labour as fiscally profligate. Whichever narrative prevails will go a long way to determining whether Robertson delivers a third-term budget.

– Richard Shaw, Massey University

The government in the economy

Budgets are generally no longer a surprise – most things are telegraphed well in advance. This is deliberate as mistakes happen when households and businesses have to play “guess what the government is thinking”.

A slight surprise was the one-off cost-of-living payment to those earning under $70,000. While no doubt any extra money is welcome to those struggling, the amount does need to be put into context. At the median wage of about $57,000 a year, an extra $350 is equivalent to a 0.6% pay increase. Inflation in the first quarter of 2022 alone was 1.7% and 6.9% for the year, and this is a one-off payment – you don’t get that money on an ongoing basis.

This budget also entrenches a bigger government presence in the economy.

In 2016, core crown expenses of $74 billion equalled 29% of gross domestic product (GDP). Core expenses are projected to be $127 billion (about 33% of GDP) for the year ended June 2023, and $138 billion (31% of GDP) by 2026. At the same time, tax revenue has grown from $70 billion (27.5% of GDP) in 2016 to a projected $116 billion in 2023 (30% of GDP).

Tax revenue is projected to grow to $138 billion by 2026 – or by about 6% per year – by which point it will be around 31% of GDP and the government’s books will balance once again. Under the current expenditure settings, significant changes to tax thresholds or rates seem unlikely.

– Stephen Hickson, University of Canterbury

Leaving poor children behind

The centrepiece of the budget’s cost-of-living response – a temporary three-month cash payment of $350 – targets families earning under $70,000. Cash injections, when targeted and adjusted appropriately, are important poverty tools, allowing families to plug gaps in vital expenditure.

The problem, however, is that such payments aren’t targeted progressively and bypass those who are really being “squeezed” – the lowest income families who are most likely being kept in poverty by our income assistance programmes, and who are not eligible for this cost-of-living payment.

Indeed, Treasury’s own estimates predict that, while all families’ incomes should increase in the next few years, middle-class families’ incomes are projected to increase at a faster rate than those at the bottom of the income distribution.

We shouldn’t be surprised by the most vulnerable families being forgotten in the budget announcements today. The government had announced changes to benefit rates (decried by child poverty experts at the time as not enough) ahead of the budget and signalled this was already “enough”.

But the announcement that child support payments will go directly to parents on benefits (rather than being paid by the other liable parent to the government) is a welcome change that will lift some children out of poverty and reduce another punitive barrier to supporting the well-being of families that don’t fit the nuclear norm.

By the government’s own budget projections, the already modest child poverty targets set last year won’t be put back on track. In fact, they’ll fall well short of estimates based on a relative measure of income before housing costs are included, and only just squeeze into the margin of error on a measure of fixed income after housing costs are included – a short-term target that was easily met last year.

This budget will be remembered as the first to demonstrably leave poor children behind.

– Kate Prickett, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

No step-change on climate change

With the announcement of the Emissions Reduction Plan on Monday, there were only a few surprises left for budget day: an additional $47 million went to climate adaptation, $16 million for community-based renewable energy, a $73 million top-up for the Warmer Homes programme, and $132 million to extend the public transport fare reduction for two months, or longer for Community Services cardholders.

Otherwise, the budget confirmed fiscal commitments we already knew, such as the ten-fold boost to decarbonisation funding at $678 million, and $350 million for cycleways and public transport. The ERP proposal for mission-led “climate innovation platforms” appears to be unfunded.

All up, the transport sector receives $1.3 billion, energy $692 million and agriculture $380 million. As a complement to the Emissions Trading Scheme, this policy mix is expected to reduce emissions by 95 to 228 metric tons over the next three emissions budgets until 2035.

But what about the government’s hints that, after underwhelming investment on climate action in past years, 2022 would be the year of the climate budget? If we exclude the extraordinary spending of the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund, then ordinary spending on climate-related initiatives through the budget process has only gently increased.

Building on earlier analysis, we estimate that at least $3 billion was allocated to climate-positive initiatives in 2022, compared to $1.4 billion in 2020 and $2.8 billion in 2021. Without a doubt, this year’s climate-related expenditure is more coherent and targeted, but not obviously a step-change.

– David Hall and Nina Ives, Auckland University of Technology

A mixed bag for health

Health was a clear focus of the budget ahead of the health system restructure. The $1.8 billion funding increase for year one, with $1.3 billion in the second year, will give the system a needed boost as it adapts to the reforms. The last thing we need is a seriously underfunded system unable to cope in a period of significant change.

Aside from the additional operational funding, the budget was a bit of a mixed bag for health. Mental health services received a significant boost, including for school-based mental health and well-being support and specialist mental health and addiction services. These initiatives are important for the government to deliver on improving well-being.

Additional funding for air and road ambulance services will be important in maintaining and improving service quality. The $191 million in additional Pharmac funding over two years will also be welcome news for many. However, it’s still likely to leave some people disappointed, as the budget doesn’t give clear directions on what that additional funding will be spent on.

The equity pay deal with support workers is set to expire, so it was good to see further commitment of $40 million per year. However, there was no specific response to calls for improved pay for allied health workers.

Health workforce development has been allocated additional funding to support the delivery of kaupapa Māori and Pacific services. This and other initiatives will be important for health equity. However, the budget doesn’t offer further specific commitment to overcoming the shortage of general practitioners. The need for a third medical school in New Zealand is becoming increasingly urgent.

Overall, more funding for health is always going to make things look better than less funding. The big questions now lie in how successful the overall reforms of the health system will be.

– Michael Cameron, University of Waikato

David Hall is affiliated with the Forestry Ministerial Advisory Group.

Michael P. Cameron receives funding from Te Hiringa Hauora/Health Promotion Agency.

Kate C. Prickett, Nina Ives, Richard Shaw, and Stephen Hickson do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.