Few developments in human history have had as much an impact on everyday life as the mobile phone. The average person picks up their handset more than 50 times a day, not just to make and receive calls, but to send emails, stream video, and play games.

The ability to communicate with anyone else in the world from any location was revolutionary in itself. But since the 1980s, advances in technology have allowed the mobile phone to consume all other manners of personal electronics, including the calculator, the digital camera, the MP3 player, and the personal digital assistant (PDA).

Mobile phones are now as powerful as a home computer and mobile networks have advanced so that we have the entire internet in our pockets. We live in the era of the smartphone – a multi-purpose device that governs virtually every part of our existence, transforming society, entertainment, and the economy.

More than half the world owns a smartphone, and there are now more than 8.4 billion active mobile connections globally, according to Ericsson.

Early smartphones and the mobile internet

Adoption peaked in the 2010s, but the story of the smartphone goes back much further – to the very start of wireless communications. Even as the first commercial handsets made their way into the hands of those who could afford them, engineers were seeing how mobile networks could carry more than just voice traffic, while manufacturers were seeking to fuse the mobile phone with the computer.

The first devices we would recognise as smartphones appeared in the early 1990s. One of the most prized items in the Mobile Phone Museum’s collection is the IBM Simon. Launched in 1993, the IBM Simon was ahead of its time in acknowledging that the future of mobility and computing was converged, combining a mobile phone, with a graphical user interface (GUI), a file system, and productivity applications into a single package.

Announced in 1996, the Nokia 9000 Communicator appeared to be a standard handset on the outside but opened up to reveal a full QWERTY keyboard and large display. It boasted an array of productivity tools, supported third party applications, and could even access the internet.

The pdQ, created by PDA pioneer Palm and Qualcomm, arrived in 1998, and the following year saw the first handset to market itself as a ‘smart phone’ arrive - The Ericsson R380. Ericsson’s effort used an operating system that eventually became Symbian and boasted a touchscreen – nearly a decade before it became an industry standard. It was almost beaten to the punch by another Ericsson handset, the Ericsson GS 88, a dual screen device that boasted two different operating systems - one for the phone part of the device and GEOS for the PDA element. Interestingly, this OS from Geoworks also powered the Nokia 9000 Communicator. In the end, Ericsson decided to go all-in on Symbian and the commercial launch of the GS 88 was abandoned with only 200 units ever made. This allowed the Ericsson R380 to take its place in history.

While many of the early smartphones included some sort of data transfer or primitive internet access, the majority of functions were self-contained. The advent of mobile broadband changed everything, powered by code-division multiple access (CDMA) technology, developed by Qualcomm in 1988, that allowed multiple radios to share the same frequencies and therefore increased the number of phones that a mast could support. CDMA transformed 2G and provided the foundation for 3G networks and the mobile internet revolution.

The first commercial 3G networks went live in 2002, unlocking a whole new wave of use cases that went beyond voice and text. Qualcomm’s efforts helped evolve mobile broadband into an infrastructure that could support video conferencing, streaming video, music, games, imaging and video recording. Transmission rates were glacial by today’s standards, but the ability to watch football highlights on the bus – minutes after the final whistle – was unprecedented.

The high cost of 3G spectrum licences in many markets, coupled with a lack of consumer demand, hindered the development of next-generation networks but the technology was essential in enabling the first wave of what we might recognise as the modern smartphone in the 2000s.

Nokia, which had created camera, music, and gaming phones, was at the forefront with the N95, while Microsoft’s periodic attempts to extend its desktop dominance to mobile saw several Windows Phone-powered efforts from several manufacturers.

But if there is one vendor who defined this era it was Research in Motion (RIM) and its BlackBerry range. BlackBerry devices were void of gimmicks and were initially the preserve of businesspeople wanting to send and receive emails using a full QWERTY keyboard. However, their high production values and exclusivity made them highly desirable items among consumers – especially those who wanted access to the BlackBerry Messenger service (BBM).

The iPhone changes everything

Despite this hotbed of innovation, the most iconic and fondly remembered devices of the decade, such as the Motorola RAZR, the LG Chocolate, and the Sony Ericsson W800, weren’t actually smartphones. It would take arguably the most design-focused and influential technology company in the world to bridge this gap and make smartphones essential.

The history of the smartphone can be divided into two eras before and after 2007, the year the first iPhone hit the shelves. While Apple’s inaugural effort lacked an advanced camera, 3G connectivity, and even an App Store, its ability to fuse a mobile phone, iPod and an intuitive operating system into an attractive, full-touch screen design paved the way for a new era of mobility.

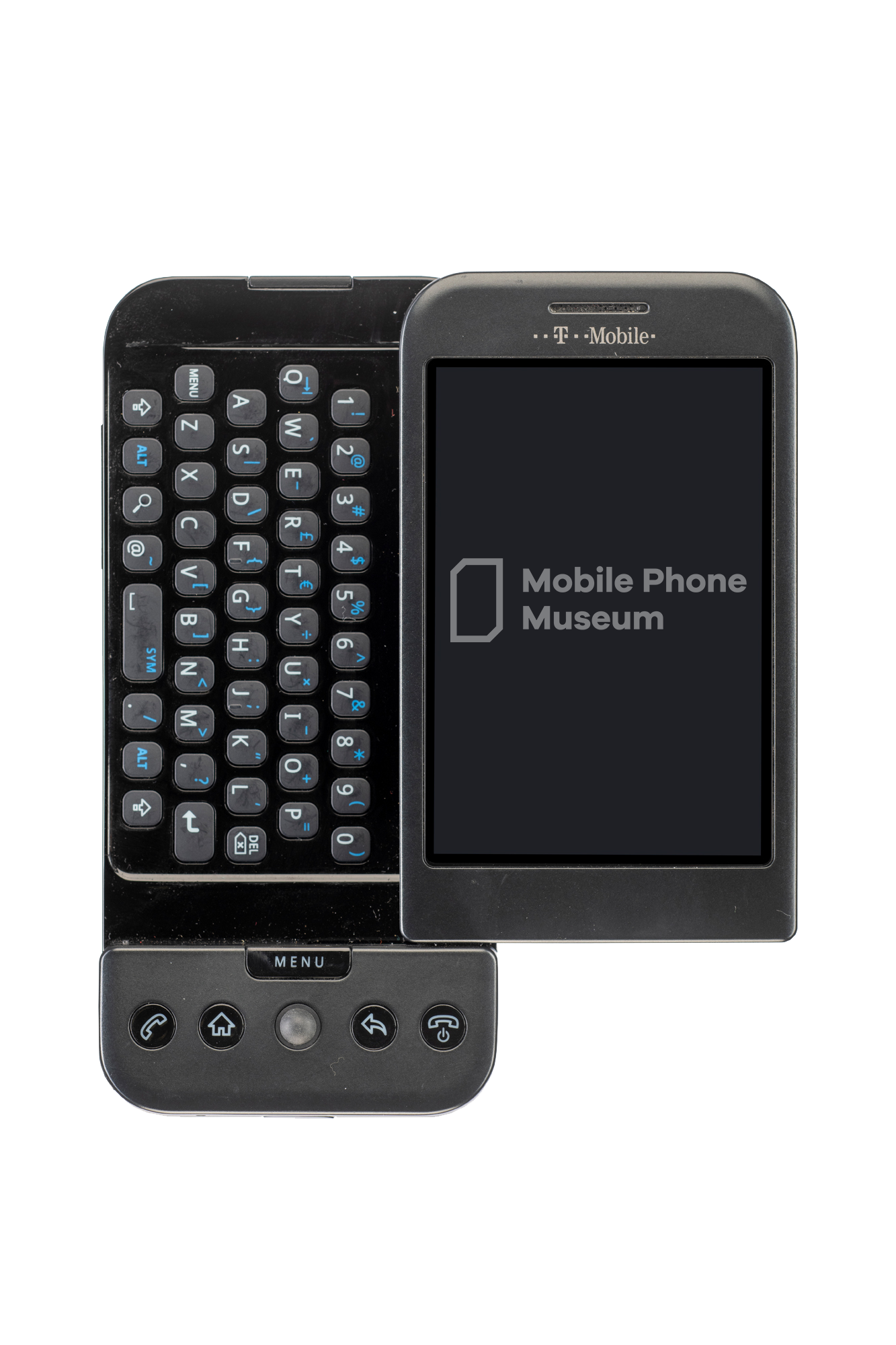

It might have been game over had it not been so quickly followed by the first Android-powered handset, the HTC-manufactured T-Mobile G1, just a year later. Android offered a competing operating system that would allow other manufacturers to create devices offering a similar experience to Apple’s gamechanger.

Android’s contribution would be matched by Qualcomm. The year 2007 also saw the first Snapdragon system-on-a-chip (SoC), giving smartphones access to 1GHz of processing power, the ability to support 720p video, 3D graphics, and a 12-megapixel camera. Snapdragon platforms would go on to power the majority of leading flagship handsets and transform what smartphones were capable of.

Qualcomm innovations can be found elsewhere in virtually every smartphone, whether its location-based services that power many common applications, wireless charging, and faster connectivity.

There were more than one billion 3G connections by 2010 but there was an understanding that even faster speeds and greater capacity would be needed to realise the full potential of these new mobile experiences. 4G, or Long Term Evolution (LTE), became the new global standard, delivering speeds similar to a home broadband connected and enhancing reliability.

By the mid-2010s, the world of mobility had converged around two ecosystems – Apple and Google. Efforts to offer a ‘third way’ fell by the wayside. Microsoft’s Windows Phone was much loved by its supporters but not even the acquisition of Nokia could establish it as a major player, BlackBerry OS 10 was too little too late, while upstarts like Tizen, Sailfish, Firefox OS, and Ubuntu Mobile failed to gain traction.

Applications were a key factor. When it launched in 2008, the App Store wasn’t the first mobile marketplace – Qualcomm’s BREW app store launched in 2001 and handled billions of transactions long before Apple had a phone – but it provided a platform for third party developers to get their wares onto the iPhone and generated an entire digital economy. Google Play, and a number of third party applications, did the same for Android.

Any challenger platform required the most popular apps on their device if they were to win over consumers, but developers weren’t going to support an OS if it didn’t have a large enough audience. It was a chicken and egg scenario.

The digital hub

The main form factor innovation of the period was size. Whereas the flip and slider phones of the 2000s were obsessed with packing more functionality into a smaller package, the phablet looked to bridge the gap between phone and tablet. Samsung’s Galaxy Note range was initially greeted with derision, but eventually commanded a loyal fanbase and influenced others to create larger screen devices – most notably Apple.

By the end of the decade, the smartphone had become the focal point for our digital lives, surpassing the home computer as the main method of access with the internet and digital services. Increasingly, mobile phones are now a hub for a range of other technologies, such as smartwatches, smart home appliances, and e-health sensors. The Internet of Things (IoT) is now a reality.

This trend will be accelerated by the further development of 5G networks capable of multi-gigabit speeds, huge advances in capacity, and ultra-low latency – characteristics that will enable entirely new applications in the field of virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR), cloud gaming, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Meanwhile, flexible display technology is ushering in a new era of form factor innovation, as evidenced by foldable handsets like the Samsung Galaxy Z Fold, Galaxy Z Flip, and the Oppo Find N2 Flip. We could even see the advent of the ‘rollable’, if the Motorola Rizr concept phone ever comes to market.

The smartphone has come a long way since the days it was described as a ‘computer with a phone’ and, if recent launches are anything to go by, the future is incredibly exciting.