The scrubby harbour-side hills of a South African city recently revealed details of an historical event that transformed Australian coastlines. That event led to the arrival in Australia of a native South African shrub, bitou bush. The invader went on to become one of Australia’s worst weeds, smothering coastal dune vegetation.

While bitou bush has been widespread along Australia’s east coast for decades, the weed arrived in Western Australia relatively recently. The species (Chrysanthemoides monilifera subspecies rotundata) was discovered in 2012 at Kwinana, a port and industrial area south of Perth. This new invasion required urgent attention.

Knowing where a weed has come from is fundamental to managing it well. Understanding how plants are introduced to new regions can enable effective biosecurity measures to be put in place. Establishing a weed’s origin also reveals where to look for its natural enemies, such as insects or fungi, that can be used as classical biological control agents.

Our research set out to decipher how bitou bush originally entered Australia and then spread from east to west. We reveal how the chance of new bitou bush arrivals in Australia is low and better biological control is possible.

Read more: Attack of the alien invaders: pest plants and animals leave a frightening $1.7 trillion bill

Establishing relationships between populations

Earlier research on bitou bush established Australian populations went through “genetic bottlenecks”, meaning only a few plants, seeds or parts of plants arrived to begin with. However, the work was unable to identify a population in South Africa that was a genetic match to the bitou bush found in Australia.

Our new research took a more comprehensive approach to reveal plants from the South African port of East London were the likely source. Our findings suggested there was a single introduction of bitou bush to eastern Australia, with subsequent movement of material to establish the population in Western Australia more than a century later.

Travel by ballast

To build confidence in our results, we scoured historical archives in Australia and South Africa for records that could support or refute these findings. Could we turn a plausible hypothesis into a feasible smoking gun?

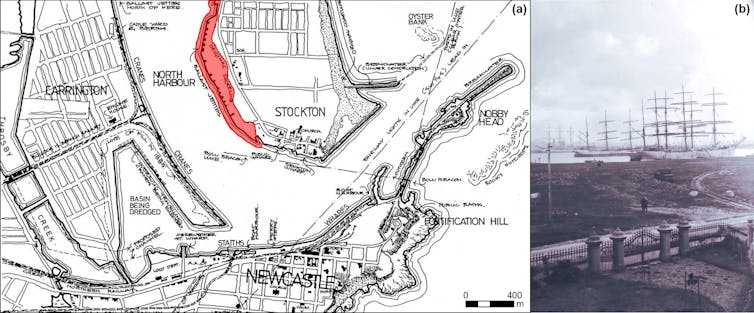

In the storage racks of the National Herbarium of New South Wales lies a pressed sheet of dried plant material. Collected in 1908, this sample – later identified as bitou bush – was from the port-side suburb of Stockton in Newcastle. Newspaper reports revealed Stockton’s local government had been complaining for at least ten years about a weed threat from dry ballast, making it likely the introduction of bitou bush to Australia occurred even earlier.

Dry ballast consists of sand, soil, rocks and other matter used to provide stability to wooden sailing ships that had to travel without a heavy cargo load. This material was usually quarried at the port of departure. At the time, an increasingly large area in Stockton was reclaimed land comprised of ship’s ballast.

We found historical shipping records that showed ships were regularly leaving the South African Port of East London after taking on dry ballast, then sailing directly to Newcastle to collect coal. Before taking on coal, these ships discharged their dry ballast onto the ballast field at Stockton. We found documents showing that in 1904, more than half the ballast arriving in Australia was dumped at Stockton.

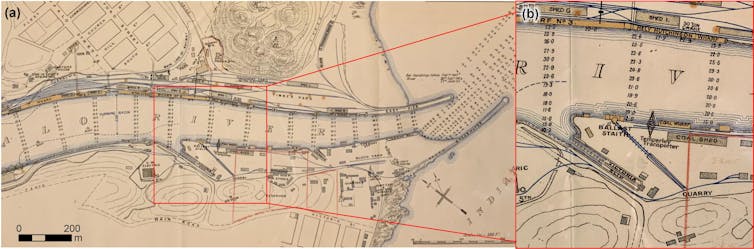

Historical maps revealed a ballast quarry on the west side of the Port of East London. This quarry existed in 1902 and exposed remnants can still be seen today. Bitou bush can still be found across the vegetation-covered hillsides near the old quarry. Their seeds are therefore likely to have been contaminants in dry ballast.

To Newcastle and beyond!

The arrival of bitou bush at Stockton was the beginning of a wider invasion of the eastern Australian coastline. The plants now cover 1,600 km from Victoria to Queensland.

This spread included deliberate plantings for dune stabilisation in the 1950s. Our molecular work revealed these dune plantings were enabled by the local collection of seed from a limited number of plants, rather than new material from South Africa or widely sourced seed.

We were not able to conclusively identify the introduction pathway from New South Wales to Western Australia. However, contamination of steel shipments between Newcastle or Port Kembla and Kwinana, or landscape plantings for the companies involved, are considered most likely.

Why does this matter?

The discovery of a potential source population and pathway into Australia for bitou bush reveals two avenues for improved invasive species management.

First, it opens the door to improved biological control. Earlier ineffective agents were sourced in South Africa from populations distantly related to the material introduced into Australia. Many effective agents, particularly pathogens, are highly host specific. New surveys around East London could discover a more effective biological control agent.

Second, the work has clarified the ongoing risk of new introductions following the same pathway. Thankfully the use of dry ballast ceased with the move to steel-hulled ships carrying wet ballast, although the latter has its own biosecurity concerns.

More generally, the case of bitou bush in Australia highlights the problem of inadvertent outcomes from introducing plants, either accidentally or deliberately, without rigorous risk assessment. We must remain vigilant to the risk of introductions facilitated by global trade and maintain strict border biosecurity protocols.

Bruce Webber receives funding from Fremantle Ports Authority and CSIRO Health & Biosecurity.

John Scott does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.