Britain is big on hi-fi. And there are some famous British hi-fi firsts we think are well worth shouting about, especially during our British Hi-Fi Week.

But before we get into it, let it be said, you have to hand it to the Americans. When it comes to sound, they did an awful lot of the pioneering work. The first record player – American; the first amplifier – American; the first headphones – American; the first loudspeaker – American. You get the idea.

So we thought we’d better give British audiophiles some ammunition in case you ever find yourself in a heated discussion in a US bar. The good news is, we have plenty to shout about...

- Check out all of our British Hi-Fi week reviews, features and news

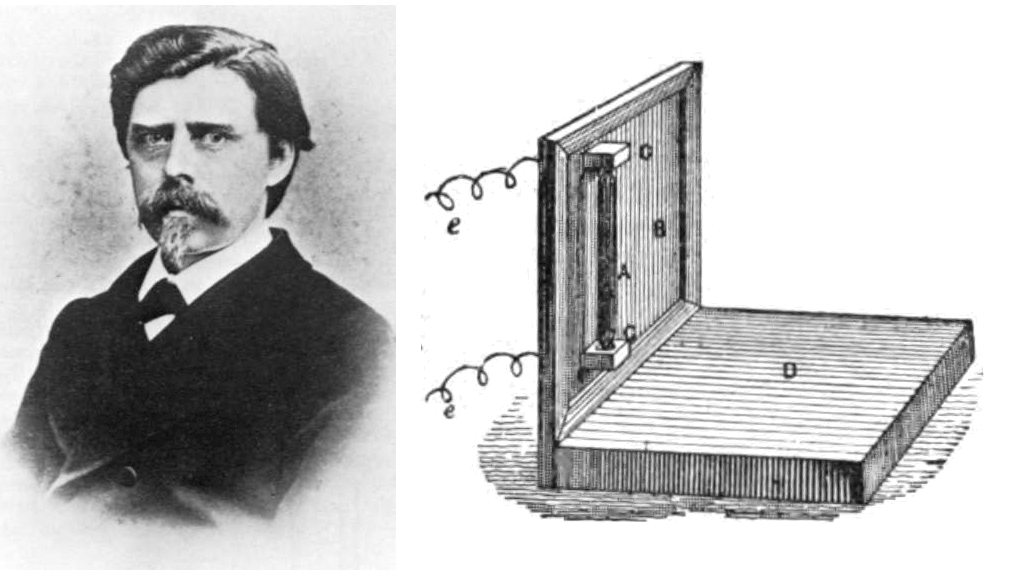

Microphone (1877)

Before the microphone, there were no audio recordings to listen to, so its creation is arguably the most significant in hi-fi. As it goes, it’s American Thomas Edison who holds the 1877 patent but historians credit the microphone’s invention to a Brit by the name of David Edward Hughes, who successfully demonstrated his creation at the Royal Society some time earlier, picking up and magnifying the noise of insects scratching inside a sound box.

Hughes’s ‘carbon microphone' was developed for telephony. It used a layer of loosely packed carbon granules sat in between two plates with a constant direct current through the assembly. One plate was a very thin diaphragm that was pushed by the source soundwaves, bringing the two plates closer together, periodically compressing the granules. This causes a change in resistance, modulating the current, which is recorded electrically as a sound signal.

Carbon microphones gave way to condenser mics and eventually the dynamic microphones we mostly see today, but there are still carbon mics in use in certain settings, such as chemical plants and mining operations where higher voltage equipment cannot be used. And there’s no doubt that it was Hughes' invention that was the granddaddy of them all. So that's one for the Brits.

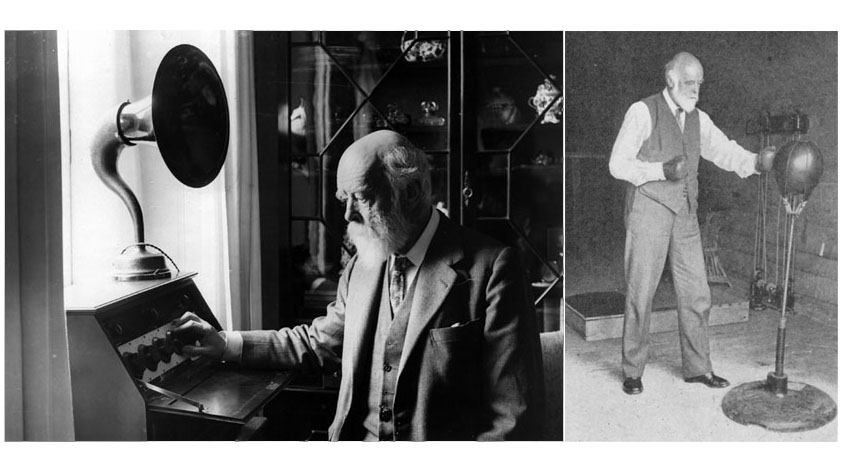

The moving coil driver (1898)

If you thought that the dynamic loudspeaker was invented by Americans Edward W. Kellogg and Chester W. Rice in 1924, then you’d be absolutely right. It was and what the pair came up with is very much the ancestor of what we use in hi-fi listening today.

But, if Kellogg and Rice were able to see far, then it’s because they were standing on the shoulders of giants – one of whom was Briton, Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge, who gained a patent for a moving coil loudspeaker in 1898; a coil connected to a diaphragm suspended in a strong magnetic field.

Lodge’s cone loudspeaker which he called the ‘bellowing telephone’, was the first of its kind after fellow Brit, Alexander Graham Bell, had created an audio ‘transmitter’ for his telephone in 1877. In those days, of course, there was very little recorded music, which is why it took more than 20 years for Lodge’s idea to be refined, completed and popularised.

Fortunately, Lodge was able to keep himself busy with the invention of the tuning radio, something which he disputed with the Marconi Company until 1912 when Marconi bought Lodge’s radio patent and gave him an honourary mention as ‘scientific advisor’ in its creation. He also liked to keep fit while wearing a suit. You can see the original Lodge Loudspeaker in the Science Museum in London.

Stereophonic sound (1931)

Eat that, everywhere else. A Briton invented stereo. In 1931, Alan Blumlein of EMI was at the cinema with his wife when he decided he was going to fix a problem with sound during the old ‘talkies’ films. With everything recorded and played back in mono, you would often get the jarring situation where the actor you were watching was on one side of the screen, yet their voice was coming out of a speaker at the other, creating a disconnect between their body and dialogue.

Blumlein began experiments in what he called ‘binaural sound’ and lodged a patent in December 1931, which was successfully awarded in June 1933. It included recording two channels in the walls of a single record groove sitting at right angles to each other, 45 degrees from vertical. The first stereo discs like this were cut in 1933.

In 1934 Blumlein recorded the London Philharmonic Orchestra playing Mozart's Jupiter Symphony in stereo at Abbey Road Studios in London, which you can listen to here. He also shot the first ever film in stereo sound called Trains At Hayes, a clip of which you can enjoy above.

Despite the obvious success, EMI decided to shelve Blumlein’s work on stereo, stating that it had no immediate commercial potential...

Electrostatic loudspeaker (1952)

Electrostatic speakers are a little different to the more conventional cone-based, electrodynamic variety. Their goal is still to move a diaphragm backwards and forwards to create acoustic waves but the way that that force is generated is different.

It’s not about voice coils and magnetic fields. Instead, a statically charged, lightweight diaphragm sits within a high voltage electric field, which is created by two electrically conductive grids on either side. The audio signal is fed into those grids and, as the current changes, so does the electrostatic field between them. This then causes a changing force on the diaphragm, which moves it back and forward accordingly. With the whole moving surface lightweight and all actively driven, electrostatic speakers can have an incredibly clean, minimally distorted and dynamic sound.

Of course, this isn’t supposed to be a physics lesson, it’s a history one – British hi-fi history to be precise. It was Cambridgeshire-based Quad Electronics that made this history when its founder, Peter Walker, unveiled the world’s first full-range electrostatic speaker in 1956 – the Quad ESL-57.

The ESL-57 used an ultra-thin stretched Mylar sheet for the diaphragm, with perforated plates either side with a potential difference of up to 10,000 volts! Their high transparency and ultra low distortion led them to be used as studio monitors at Philips and the BBC. They weren’t without their drawbacks – reliability, scale and the lack of a serious bass response – but it doesn’t seem a bad deal for just £52.

Demand for the ESL-57 was such that it stayed in production until 1995. Quad still manufacturers electrostatic speakers today, albeit considerably more refined than that first and original generation.

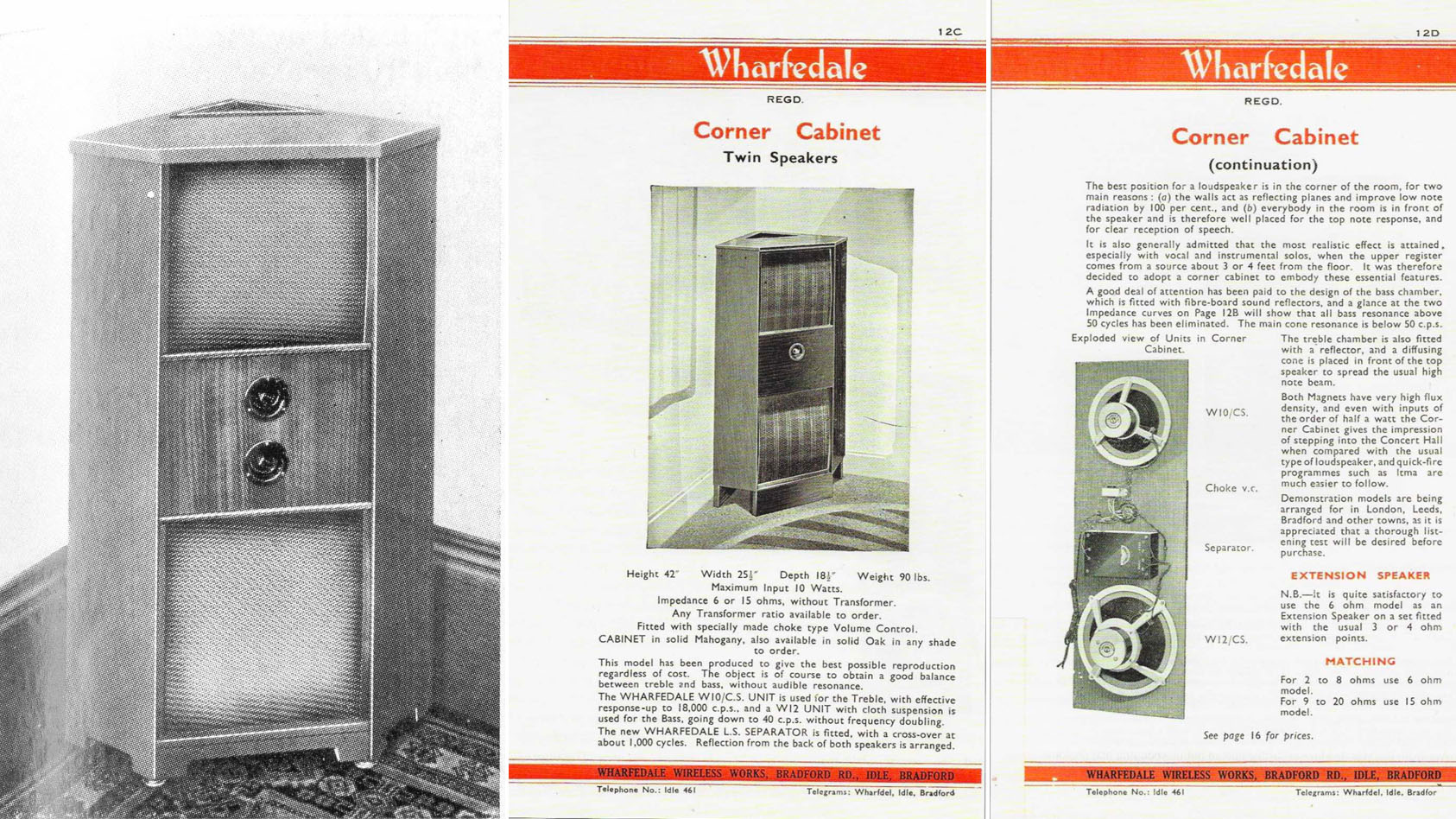

Two-way speaker (1962)

Why have one driver doing all the work, when you can create more specialised units to reproduce certain frequency bands with more care and precision? That was radio engineer Frank Thistlethwaite’s thinking when he took the idea to the founder of Wharfedale, Gilbert Briggs, in 1947.

Thistlethwaite had seen crossover networks used in cinema sound to divide the frequency spectrum between two or more loudspeakers. He set up a demo using Wharfedale speakers and the results were so good that the idea to produce the first domestic two-way speaker was born.

Quite a few years later, after plenty of engineering challenges around size and financial viability, the twin-speakered Wharfedale Corner Cabinet was born. It used a 10in W10/C drive unit for the treble, with a sensitivity up to 18kHz, and a W12/C for the bass, which bottomed out at 40Hz. The crossover took two grown men to lift.

The cabinet itself measured 42 x 25.5 x 18.5in and weighed 90lbs. It was shaped to sit in the corner of the room where the walls could “act as reflecting planes and improve low note radiation by 100 per cent”. It was made from solid mahogany or solid oak – in any shade, to order – and cost over £48, which is closer to £1400 in today’s money. Like them or loathe them, it's kept crossovers in loudspeakers ever since.

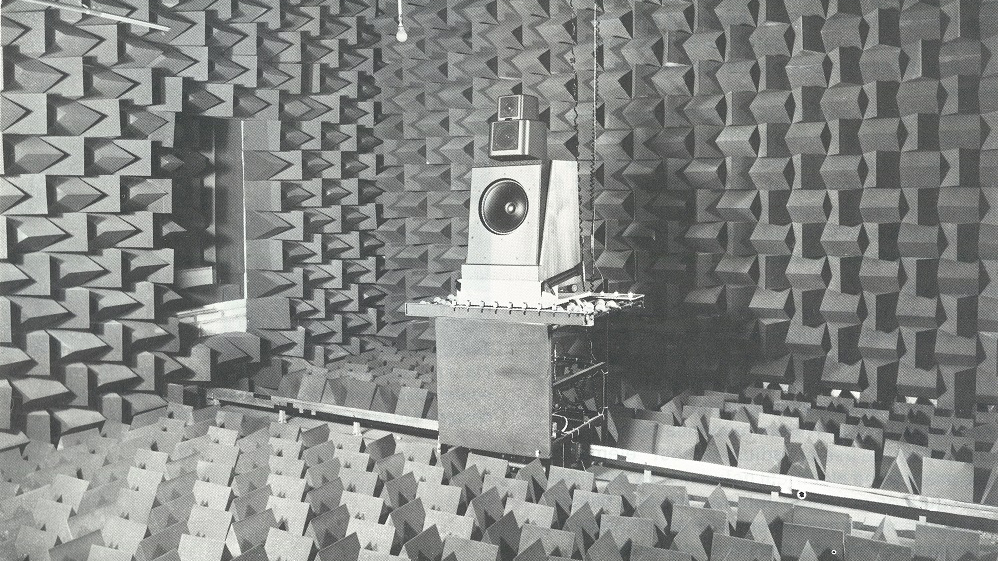

Computer-analysed speaker production (1973)

It’s not easy to nail down which hi-fi company started using computers to make their products first, but British born KEF claims its 1973 Reference 104 speakers as the first mass-market speaker engineered using digital measurements taken with a computer. Each pair that came off the production line was measured and matched to the lab reference that the engineers had worked on, hence the 'Reference' part of its title.

KEF had borrowed the computer equipment from HP in 1971 and was so pleased with how it had gone that the company invested in its own Hewlett-Packard Fourier Analyzer in 1975.

Now armed with computer measurements, KEF began creating simple computer simulations to consider the interaction of the driver and the crossover, meaning that it was the first time a crossover was designed to take that into account. It was the KEF Reference 104aB, in 1976, that was the first to benefit, which seems to make it the first loudspeaker designed using computer simulation.

Some time later another British hi-fi company, Celestion, was involved in its own pioneering computer analysis work, more specifically focused on drive unit design. In 1982 they developed a laser Interferometric system so that they could observe the breakup behaviour of loudspeaker cones. It's not likely that Celestion was the first to use computers in driver design, though, as Sony was also working on similar lines in the late 1970s.

Above is a picture of the KEF Reference Model 105 speaker which, in 1976, was another of the first phase of loudspeakers created with computer-assisted design. It worked out as a modular three-way speaker with a separate, heavily-dampened enclosure for each drive unit. A 12in bass driver housed in a 70-litre closed cabinet sat at the bottom, with the B110 midrange and T52 high frequency drivers above. It was successful enough to spawn several later versions including the KEF 105/3, rated as one of the best KEF products of all time.

Hi-res digital audio (1996)

Hi-res music files are nothing if we can’t hear them and for that you need a hi-res-capable DAC. Who was the first to make one of those? A British company, that’s who.

It was dCS who pioneered the hi-res space by launching the first ever 24-bit/96kHz-capable analogue-to-digital and digital-to-analogue converters. These were the dCS 902 and 952, which soon begat the dCS Elgar, launched as the first DAC designed for domestic use. Not long later, it also became the world’s-first 24-bit/192kHz-capable DAC, owing to a subsequent firmware update.

It was designed by Allen Boothroyd, design director at Meridian Audio, and creator of the outer cover for another British marvel, the BBC Micro computer.

Audiophile Portable DAC (2006)

Think of a DAC and the name Chord Electronics won't be far behind. While the Kent-based company wasn't the first on the scene, it's certainly taken the idea and run with it.

It was the first to supply high-end amplifiers to George Lucas’s Skywalker Sound, the sound division of Lucasfilm; the first company to supply the BBC with a modern audiophile amplifier for professional use. It was also the first (and only) hi-fi company to supply audio micro-systems to Google in the shape of 500 Chordette, which were made for Google executives.

What's more, Chord was the first to create a transportable and rechargeable reference-quality DAC so that audiophiles could enjoy top-of-the-line listening wherever they went – the Chord Hugo.

The Hugo – because hu-go anywhere with it (yes, really) – arrived in 2014 and quickly received the What Hi-Fi? five-star seal of approval, later picking up a Best DAC What Hi-Fi? Award in 2016. We loved its fantastic detail, dynamics, its Bluetooth connectivity, superb timing and organisation, and, of course, its portable design.

The Hugo has since been usurped by the Hugo 2, the Mojo and more, and there are now other companies who have got in on the portable DAC game – but it was Chord who got us moving first.

Well done, Chord – and every British audio brand with a vision. We salute you, and long may it continue.

KEF Metamaterial Absorption Technology (MAT)

Anyone who’s ever heard the startling clarity and crispness of KEF’s remarkable LS50 Meta loudspeakers will understand exactly why we dubbed them worthy of a place in our coveted pantheon of 2022’s award-winning products.

What makes the LS50 Metas truly special is hinted at in the name. The superb speakers utilise something called Metamaterial Absorption Technology (MAT), hence the ‘Meta’ aspect, an incredibly smart piece of innovation that has given KEF the edge in the hunt for razor-sharp audio fidelity.

In layman’s terms, MAT is a solution to sonic rebound. Whenever a cone vibrates, sound fires into a chamber behind the dome, and while much of this sound is absorbed by damping materials, some energy always rebounds back through the dome, creating unwanted fuzz and distortion.

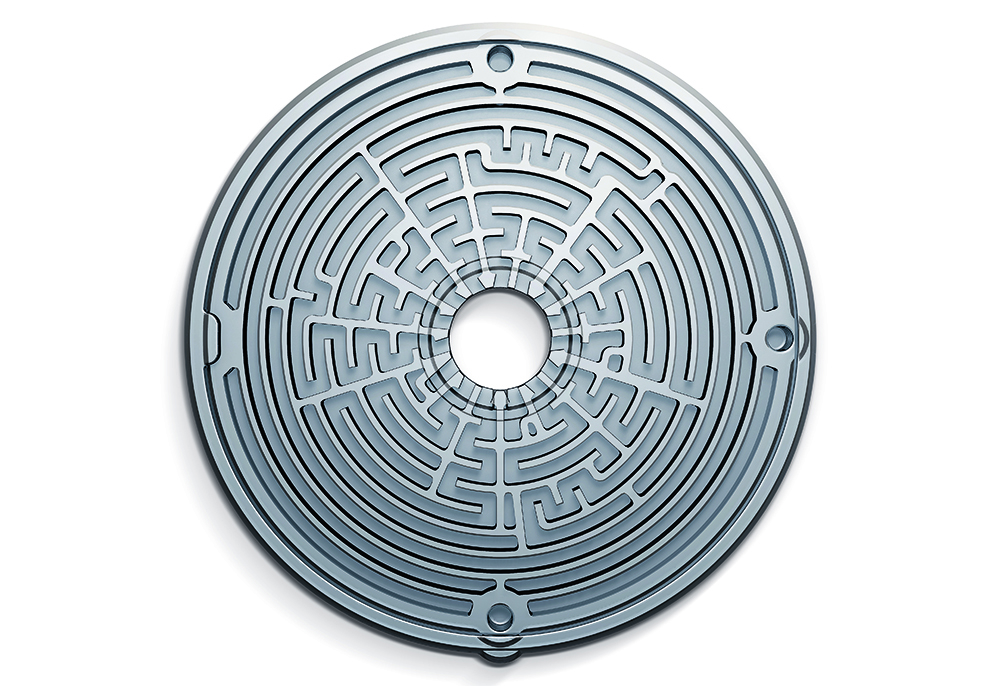

This is where KEF’s remarkable innovation comes in. The MAT is essentially a small disk-shaped device crisscrossed with rivets and channels, a bit like one of those ball-in-the-hole puzzle games you played with as a child. The sound feeds into the maze of channels and tubes, each one tuned to absorb a wide range of sonic frequencies far more effectively than a single block of damping material.

This results in a far more sophisticated, faithful audio experience at the higher ranges. The MAT can absorb frequencies from around 600Hz upwards, reducing distortion and giving a cleaner, less deformed high notes. So effective is the technology that we felt its implementation in the LS50 Meta made the company’s previous five-star R3 speaker sound “congested and ham-fisted in comparison.” A serious leap towards outstanding sonic clarity.

MORE:

We asked top British hi-fi engineers for their favourite test tracks – this is what they said

The British hi-fi Hall of Fame: every British entrant from the last 48 years

Check out all of our British Hi-Fi week reviews, features and news