Look at the front page of the Chicago Sun-Times for Monday, May 15. Inauguration Day, the day Brandon Johnson would be sworn in as the city’s 57th mayor. What don’t you see?

Well, no beaming mayoral portrait, for starters. No gushing headline, “A new era” or some such thing. The main page-one story is about a suburban mom with kidney failure.

The arrival of a new mayor gets a plug in the upper right corner: “HOW JOHNSON COULD AVOID INAUGURAL MISSTEP OF LIGHTFOOT” referring readers to an article pointing out that inaugural addresses are remembered mainly for their gaffes, and inviting political pros to speculate about ditches Johnson should take care to avoid.

That skepticism is hard-won. Survey the Sun-Times’ coverage of the fifth floor of City Hall since its birth 75 years ago, and what stands out is the progress from credulous mouthpiece to critical observer and relentless investigator, making the waves that rock the mayor’s office.

The daily Sun-Times began publication quietly — the union of the Sun and the Times was a cost-cutting move — in February 1948, and in the early years could often be found curled up in the lap of Mayor Martin Kennelly, purring contentedly.

“The public approval of the Kennelly businessman administration reflects the people’s confidence in his integrity,” a purported news article insisted on April 15, 1948. “His policy of good government first and politics last has ‘sold’ Chicago citizens though it has aroused some grumbling among the politicos.”

Though even in that praise, the unnamed writer pauses to note: “The most significant lack has been in the police department.” Some things never change.

Kennelly was a see-no-evil, hear-no-evil millionaire businessman, a bachelor who lived with his sister. The Sun-Times did notice shady doings around him. The Democratic paper had no trouble going after a Democratic administration when corruption was involved. Great New Yorker press critic A.J. Liebling, who lived in Chicago during the winter of 1949-1950, noted this about the Sun-Times in his classic travelogue, “The Second City:”

“It sometimes raises a great row with stories about local political graft. Although Chicago municipal graft is necessarily Democratic, since the city’s government is Democratic, it is the Sun-Times, rather than the Tribune, that gets indignant.”

At first, Richard J. Daley labeled ‘progressive’

As a generally liberal paper trying to counterbalance Col. Robert McCormick’s reactionary Tribune, the Sun-Times welcomed the arrival of a certain Richard J. Daley as chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party in 1952, calling him “an associate of the more enlightened progressive wing of the Democratic Party.”

When Kennelly sought a third term in 1955, the paper chided Daley for even running against him.

“What’s more shocking is that his tacit acceptance of the dump-Kennelly movement aligns him with the worst elements of the Chicago Democratic organization,” the paper editorialized on Dec. 13, 1954.

Kennelly alienated Black voters by ignoring their housing woes and targeting their wards as the focus of his anti-gambling efforts. So they turned out heavily for Daley, despite the paper’s admonitions, and he won the Democratic primary. The Sun-Times cast the general election against Republican Robert Merriam as a battle “between the forces of civic righteousness and the nefarious political bosses.” Daley represented the latter.

Daley’s victory in the general election found the paper torn between its previous opposition and the always-strong urge to dandle a new mayor. Its post-election editorial was headlined, “Chicago Ain’t Ready For Reform Yet,” the infamous blessing that colorful saloonkeeper/alderman Paddy Bauler bestowed upon the outcome. “The election of Richard J. Daley as mayor puts the old-time political hacks like Bauler back in the driver’s seat,” the Sun-Times fretted, before offering him a pro forma clean slate and best wishes, noting that Daley was a solid family man with a good reputation, despite the company he kept.

Daley had no trouble using the press — photographers were welcomed into his home to capture his doting wife and seven lovely children at breakfast. But he could easily turn against it, once countering charges of corruption with: “There are even crooked reporters, and I can spit on some of them right here!”

The paper’s hostility of 1955 had shifted to admiration by the time Daley ran for a second term in 1959.

“In the three and a half years that he has been in the City Hall, Dick Daley has been one of the best mayors in Chicago history,” the Sun-Times editorialized when Daley announced his reelection bid. “Coming from us, that is quite a compliment, for we opposed him in the 1955 Democratic mayoral election.”

What the paper didn’t point out was that in 1955 it was supporting the sitting mayor and it still was.

Coverage shifts in ’60s: ‘They’re booing the mayor!’

The 1960s saw the interjection of three elements into the Sun-Times coverage: editors and reporters who were increasingly a) younger, b) female and c) Black and Brown, then called “minorities.”

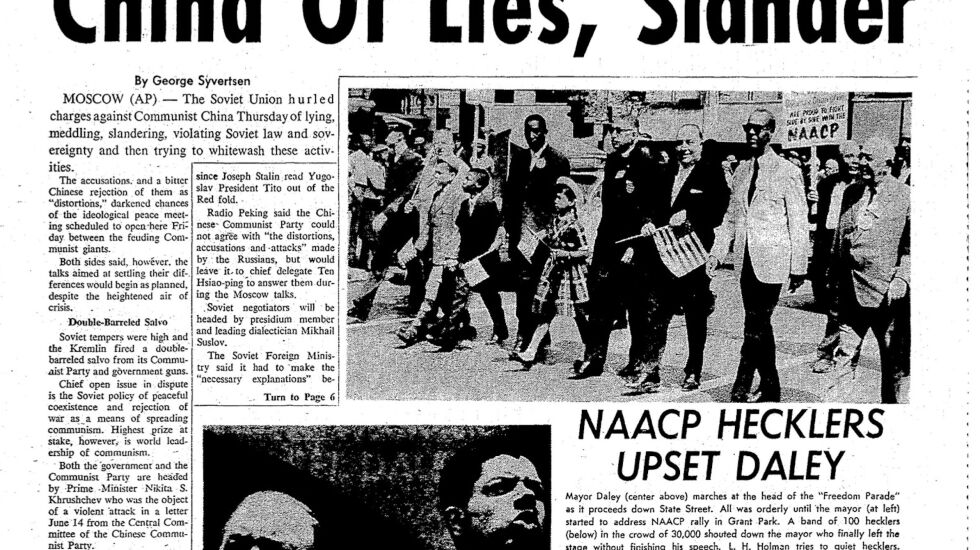

On the 4th of July, 1963, Daley led an NAACP “Freedom Parade” trailed by picketers. At a rally at Grant Park, he was booed by protesters, “a number of them bearded.”

“They’re booing the mayor!” an amazed reporter, Ken Towers, 28, phoned into the city desk.

Once the paper might have ignored those boos, or even heard them as cheers. No longer.

“NAACP HECKLERS UPSET DALEY” read the front page headline. Several protest signs were quoted. “MAYOR DALEY, NO NEGROES IN YOUR WARD, WHY?”

“When Daley was booed, it was another shock to the system,” Towers, who would rise to become the paper’s top editor, later recalled, “That should have tipped everybody that something was going on.”

Indeed it was. As the turbulence of the 1960s gathered force, the Sun-Times and the mayor squared off. After the April 1968 riots following the murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a Sun-Times piece, “STORY BEHIND RIOT TOLL: THE NINE WHO DIED,” angered Daley into claiming he had issued his infamous “shoot to kill order,” after the fact, trying to provide cover for the police who are thought to have killed at least some of those slain.

Conversely, it was Daley’s frequent taunt of “Where’s your evidence?” of municipal corruption that prompted the paper to stage its elaborate Mirage Tavern sting, a fake bar where the paper could photograph city inspectors accepting envelopes of cash.

‘Chicago still reminds me of Mussolini’s Italy’

The paper still held the counterculture at a distance until staffers — like many Americans — were radicalized after the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Nothing like being beaten by police unleashed by the mayor to shift your attitude. Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who joined the paper in 1962, hadn’t focused much on local politics until then. Afterward, he took a caustic view of the city and its mayor.

“Chicago still reminds me of Mussolini’s Italy,” he said in 1976. “I consider Richard Daley basically a Fascist and the town is sort of run that way. ... I was once forced to shake hands with him — one of the slimiest handshakes of all time. He’s really a vile little son of a bitch.”

The paper joined with the Better Government Association in 1974 to find the “$200,000 nest egg” — a secret real estate firm run by Daley and his wife, Sis, one of a steady drumbeat of investigations rattling City Hall.

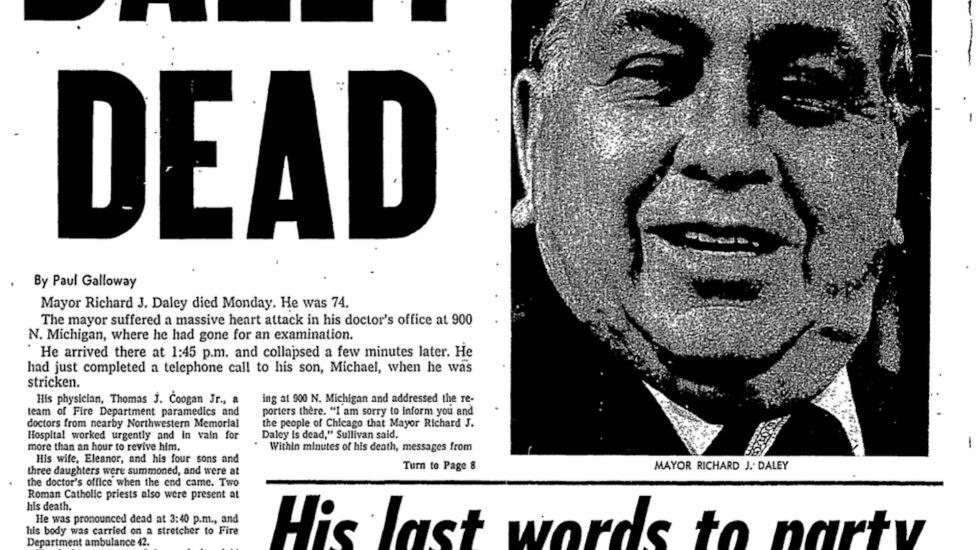

Daley died five days before Christmas 1976, causing the Sun-Times to shift into grief mode. Death settles all accounts. It offered a lukewarm welcome to the appointed placeholder, Michael Bilandic, Daley’s devoted lieutenant, initially dubbing him, “a satisfactory caretaker as acting mayor until the election of his replacement.”

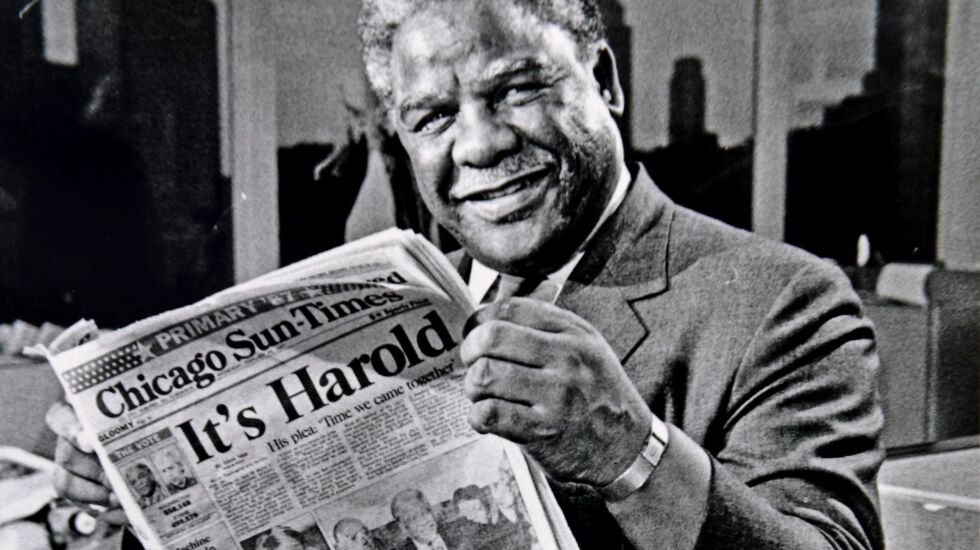

But Bilandic reneged on his pledge not to run in the 1977 special election to fill the remainder of Daley’s term. Few remember he defeated Harold Washington in the February primary before going on to win the general election that June.

Adjusting himself to power, Bilandic also ran in the 1979 Democratic primary.

Both Bilandic and his freshly fired head of consumer weights, sales and measures, Jane Byrne, claimed to carry the mantle of the late mayor. Sun-Times columnist Mike Royko held a print seance to contact Daley and see whom he really favored, using the mayor’s trademark mangled syntax as he accuses the columnist of:

... putting implicinsinuendoes in my mouth again. No, I’m not endorsing either of them. Chicaguh is the greatest city inna world, wit the most wunnerful people, and it should have the greatest mayor inna world.

Meaning himself. Royko gingerly points out to Daley that he’s dead and can’t run for office.

Why not? Bilandic’s running the city, and I’m in better shape than he is.

Royko had come to the Sun-Times when the Chicago Daily News folded in March 1978. He blasted away at Bilandic, who botched the city’s response to the 1979 blizzard and was, in general, tone deaf and feckless. Royko pushed hard to get Byrne elected, all the while reflecting the unexamined sexism of the day — calling her “little Ms. Sourpuss,” urging her to smile more.

The paper’s editorial pages endorsed Bilandic, faulting Byrne, ironically, for having been part of the Daley administration.

Byrne was ‘Mayor Bossy’; Washington’s war with Council

After her surprise election, Royko quickly realized Byrne was embracing the insiders she had run against. He turned on her, writing on April 4, 1979:

The vision was nice while it lasted. But it didn’t last too long. For me it began ending the day Eddie (The Sewers) Quigley planted a kiss on MS. Bossy’s lips and she neither slapped him nor had him arrested as a public nuisance. ... After that it was a month-long love fest between Ms. Bossy and every ward boss and alderman who would slobber on her shoes.

Royko would call her “Mayor Bossy” for the rest of her term. For her part, Byrne nevertheless preferred the Sun-Times to the Tribune — less condescending — though she cringed whenever its dean of City Hall reporters, Harry Golden Jr., called her “MAHdam Mayor” instead of simply “Mayor.”

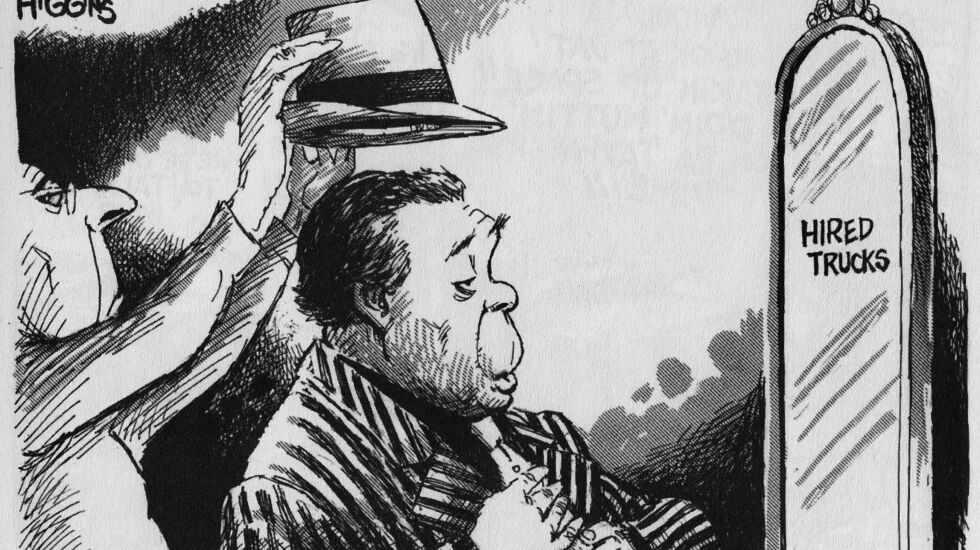

During the Byrne administration, the paper added another mayoral scourge: editorial cartoonist Jack Higgins.

Under his pen, Byrne became the Morton Salt Girl, merrily pouring boodle from a big canister labeled “City $.”

Seeking reelection in 1983, Byrne split the white vote with her arch-nemesis, Richard M. Daley, and Harold Washington squeaked past them both into office. It was a time of Council Wars and competing factions feeding stories, or what they hoped would be stories, to their allies at the papers.

We know how Washington viewed Sun-Times reporters through press secretary Alton Miller’s memoir. Pulitzer prize winner Tom Fitzpatrick was “writing nasty stuff, sneaking in sexual innuendos.” Basil Talbott was “terminally cynical.” Fran Spielman, newly hired at the paper, was so focused on uncovering “incompetence and corruption” that she was “considered irreparable” as a potential mayoral ally.

Washington’s sudden death on Thanksgiving 1987 shocked the city. Like Bilandic, Eugene Sawyer was another appointed placeholder — the Sun-Times detailed how white aldermen made under-the-table deals to anoint him.

The 22 years of Daley the Younger were covered by Spielman, and since Daley has vanished into near seclusion, she is best positioned to characterize his relationship with the paper.

“In the early days, he was uncomfortable, self-conscious,” she said. “How awkward a person he was! He was so guarded. So suspicious. He grew up in the spotlight and thought everybody was out to get him.”

Like his father, Daley could explode at the press.

“Scrutiny?” he fumed, when asked about news coverage of his brother. “What else do you want? Do you want to take my shorts? Give me a break, go scrutinize yourself. I get scrootened every day, don’t worry, from each and every one of you. It doesn’t bother me.”

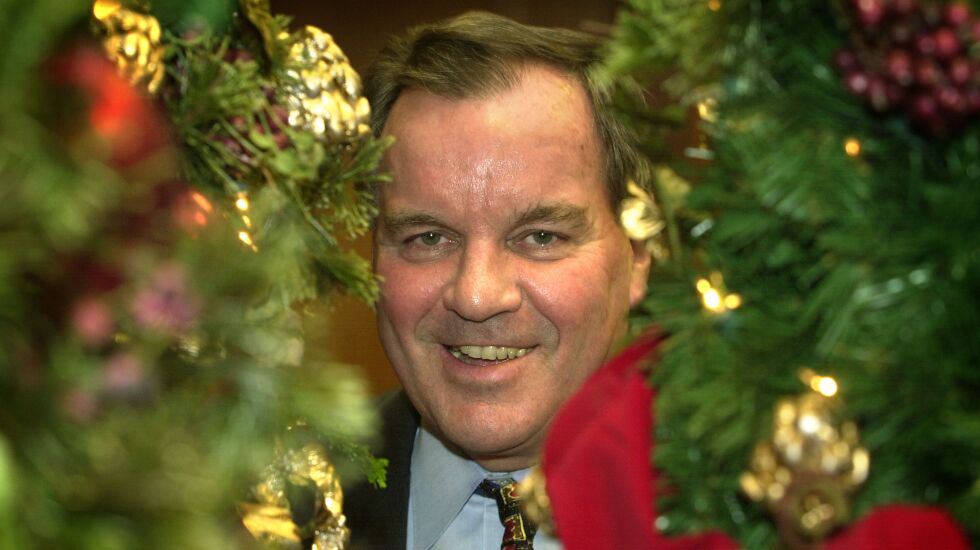

In his defense, Daley could be a good sport. A Sun-Times editor concocted a lighthearted “12 Days of Chicago Christmas,” holiday section, posing Koko Taylor sitting in Tiffany’s showing off five golden rings and coaxing 10 aldermen to leap for a photo. The partridge in a pear tree had to be Daley, and hizzoner played along, gamely posing with his face framed by the green branches of his office Christmas trees.

But that was in 2000.

“As his administration went on, the scandals started to mount,” said Spielman. “Hired truck, city hiring, minority contracting, Koschman, Daley’s son getting a sewer contract — all of these things were Sun-Times stories,” said Spielman. “As time went on, he became more and more insular. His circle tightened even further. He trusted fewer and fewer people, even though he trusted no one in the first place.”

Spielman, as the face of the paper, took the brunt of it.

“As he became more and more insular, he became more and more abusive to me,” she said. “Whenever I asked a question he would ridicule me. I was bloodied and battered, but I kept on asking. I was proud to take the abuse because [Sun-Times investigative reporter] Tim Novak had done such a fabulous job in all his investigations, and I was proud to work at a newspaper that had done that.”

Rahm Emanuel: ‘He’s our jerk’

Daley took his ball and went home in 2011, turning City Hall over to Rahm Emanuel. The former White House major-domo and congressman was a far smoother operator than Daley. He’d invite reporters in for chatty coffees, phone them at home, inquire cheerily about stories they were working on. As a candidate, he showed up in a bar where Sun-Times columnist Mark Konkol was having a drink, leading to this exchange, recorded in Konkol’s column:

You’ve got schmutz on your chin, he said, grabbing a cocktail napkin and reaching up to gently wipe unintentional leftovers from my bushy beard.

Emanuel let loose with a giant smile. Everyone around us had a good laugh.You get elected and I’m telling everyone the mayor wiped schmutz out of my beard, I said.

Deal, Emanuel said. Say what you want about our new mayor — he’s a bully, an arrogant jerk, a power-mad potty mouth — the guy wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty when a little schmutz needed to get cleaned up.

That blend of affection and criticism — when he began — seemed the proper reaction to Emanuel’s sharp-elbowed style. “He may be a jerk, but he’s our jerk,” is how I put it.

But like all mayors, Emanuel hated bad press. “Rahm Emanuel,” I used to say, “cares so much about his image, it makes him look bad.”

“Rahm was terribly controlling,” remembers Spielman. ‘If he didn’t like a comma you wrote, he took it personally. He was more hurt, especially, by negative headlines. Whereas Lori Lightfoot, if a comma was out of place, she thought you were out to get her.”

I found that to be the case as well. Though Lauren FitzPatrick and I had written a well-researched profile — I dug up her high school yearbook and spoke with her wife, FitzPatrick traveled to Ohio to talk with her mom — Lightfoot never spoke to me on the record in four years in office.

Not when I served her softballs, asked her to go up to the rooftop, smoke cigars and talk about bees — maybe because the City Hall hives were apparently banished under her watch.

Spielman’s experience was similar.

“She literally did not talk to me after the first year of her administration,” said Spielman. “She. Could. Not. Take. Criticism.”

Brandon Johnson arrives to find a new sort of Sun-Times. We are now under the umbrella of Chicago Public Media, and as a nonprofit, we don’t endorse candidates anymore.

But there’s every reason to expect that over the next 75 years, the Chicago Sun-Times will fill the role it always has: to celebrate and condemn, magnify and reduce, weigh and measure, explain and advise, whoever assumes the heavy responsibility of being mayor of Chicago.