Just three years after The Day The Earth Stood Still raised the bar for Cold War sci-fi, British company Princess Pictures also produced a film in which a humanoid alien comes in peace to warn Planet Earth about the dangers of nuclear weaponry. Unlike its obvious inspiration, though, Stranger From Venus doesn’t boast an eight-foot-tall robot, eerie theremin-based soundtrack, or anything else that could be even remotely described as otherworldly.

A blink-and-you-’ll-miss-it shot of a hilariously unconvincing flying saucer (most likely a couple of pan lids) and a brief magnetic glow are the only special effects in a stagey, super-serious movie that treats the monumental meeting between mankind and extraterrestrials with all the wonder and amazement you’d expect for a town hall filibuster. Never let it be said the Brits broke their stiff upper lip.

Celebrating its 70th anniversary today, Stranger From Venus sets the lo-fi tone from the offset when countryside driver Susan (Patricia Neal) crashes into a tree after being blinded and deafened by an overhead spaceship that stays resolutely off-screen.

Luckily for the film’s sole American, she’s rescued by a mystery man (Helmut Dantine) who soon becomes a person of interest when he wanders into a nearby country inn. Who is this outsider who can read patrons’ minds and miraculously heal car crash victims (Susan soon follows him in with barely a scratch), all without a pulse? “There are two possible explanations for this: I am drunk, or you are dead,” Dr Meinard (Cyril Luckham) surmizes in one of the film’s best deadpan lines.

The medic may have had a few, but the man known only as The Stranger isn’t a walking corpse. Nor does he look particularly out of place; although director Burt Balaban teases otherwise by initially shooting him solely from the back of his head, he’s of human appearance (even his personal force field is invisible).

Instead, as the matter-of-fact title suggests, he’s simply a visitor from Venus who’s there to make a galaxy-saving deal: if Earth stops developing the nuclear technologies that are threatening to change the gravitational pull of every single planet within the solar system (50 detonated hydrogen bombs is the magic number, according to all the gobbledygook), then his homeland will share their own higher scientific powers.

A handful of locals are instantly intrigued. Reporter Charles (Kenneth Edwards) tries to develop an understanding of The Stranger’s mission, learning of his multilingual skills, how his spacecraft is powered by interplanetary magnetic energy, and that, like the Thermians in Galaxy Quest, his race has built up their knowledge of Earthlings via TV and radio broadcasts. “I usually hate people who know all the answers, but I like him,” the journalist says. “He makes you feel like a moron, but I like him.” Furthermore, there are flickers of a possible romance with Susan as the pair continue to bond while tending to the inn’s enchanting garden.

The general response to his presence, however, ranges from suspicion to downright hostility. While The Stranger hopes to assemble world leaders to discuss strategy, the British government decides to deal with the matter in-house. They cordon off the inn where 95 percent of the “action” takes place, confiscate his communication apparatus, and set a trap in an attempt to wrestle control of his mothership for their own ill-gotten gains. Humans are going to human.

This shortsightedness soon backfires, though, when The Stranger discloses that such a takeover would result in a retaliation that would instantly wipe out the whole country. With Arthur’s help, the communication device is returned to its rightful owner, allowing him to warn off his fellow aliens and head back home with his mission unfulfilled but everyone’s lives intact, for now.

Acknowledging that humanity can be its own worst enemy, it’s a sobering and uncertain conclusion that also echoes The Day The Earth Stood Still. It’s also one fitting for a film that, whether due to creative choice (or, more likely, budget constraints), avoids the hysteria and bombast of most alien invasion B-movies.

Admittedly, its inherently talkative nature often struggles to compel. Even at a slim 75 minutes, Stranger from Venus often drags, with the screenplay needlessly dedicating just as much time to barroom orders as world-saving negotiations. Its flat direction and claustrophobic setting scream regional theater, not big-screen experience.

The movie also appears to take place in an off-kilter alternate universe. Although the majority of the cast speaks with a British accent and the setting bears all the hallmarks of the English countryside, the film’s radio transmissions are clearly American, the military uniforms are distinctly Eastern European, and the governmental positions (president instead of prime minister, Secretary of the Interior) are all over the place.

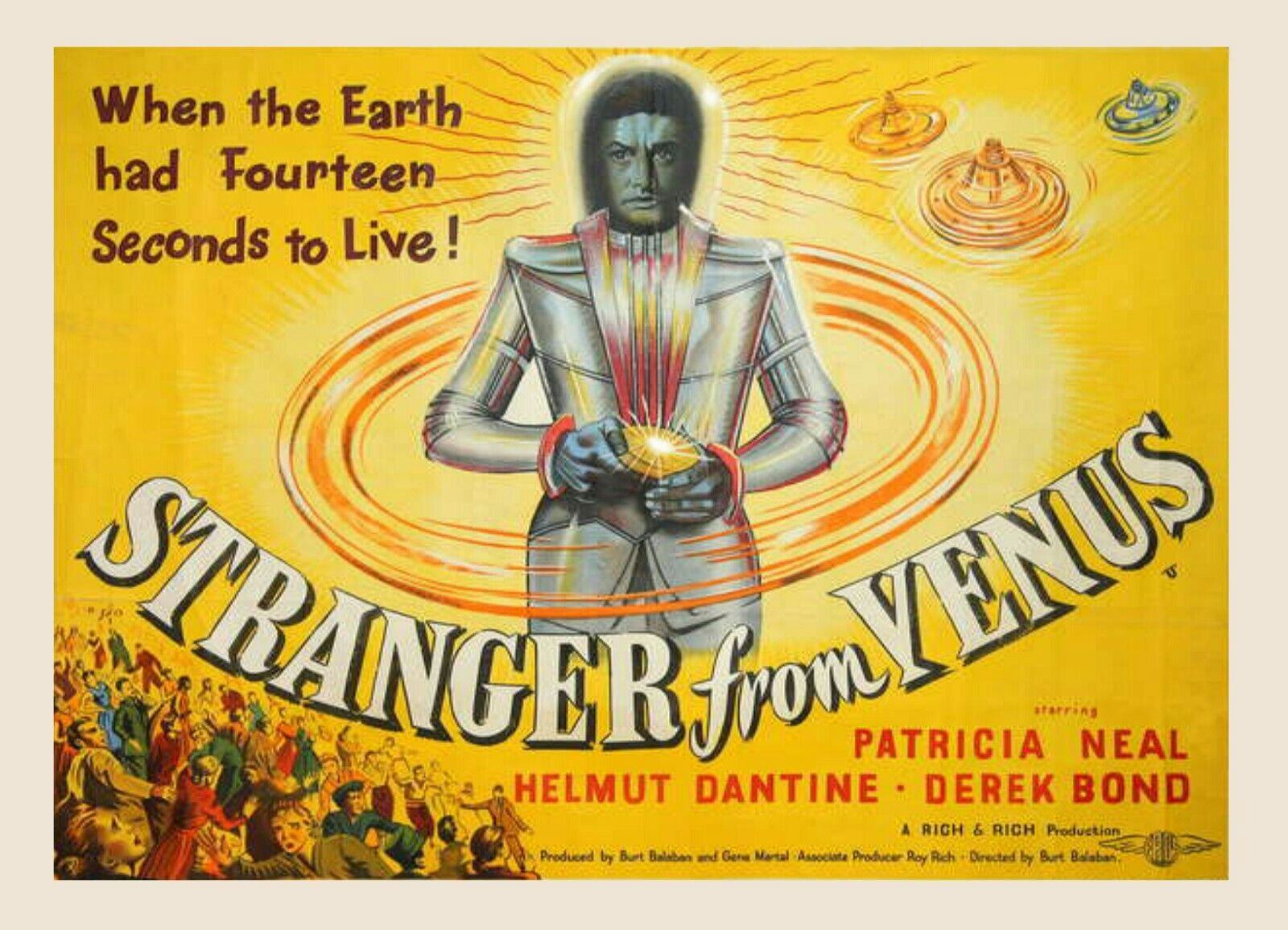

Stranger from Venus doesn’t quite reflect its alternate title, Immediate Disaster. It’s competently acted, for one thing, and its messaging remains timely. Yet it’s fair to say the eye-catching poster, in which a more Hollywood-friendly alien towers above a terrified crowd with the caption, “When the Earth has fourteen seconds to live,” set a new benchmark in false advertising.