Mountains – their height, their mass, their climates and ecosystems – have fascinated humans for thousands of years. But there is one that holds extra-special meaning for many – Mount Everest, or Chomolungma as the Nepalese Sherpa people call it.

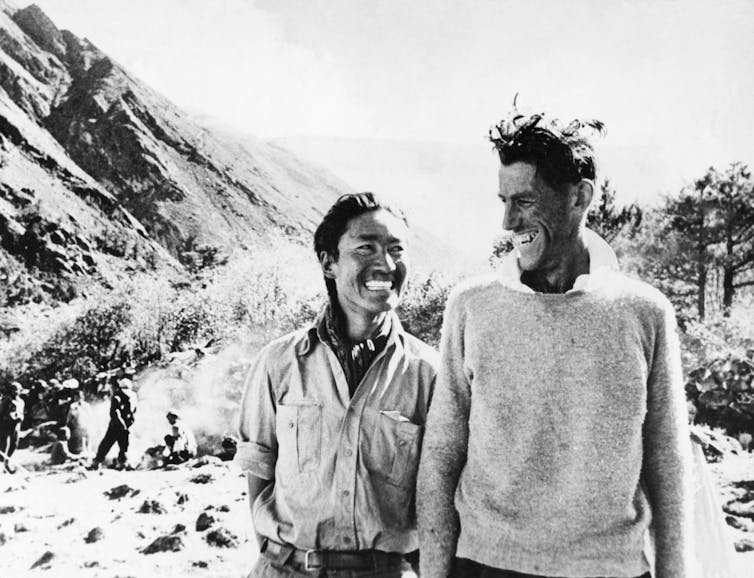

A sacred mountain for some, for others the world’s highest peak represents a challenge and a lifelong dream. Seventy years ago, on May 29, 1953, that challenge and dream became reality for two members of a British expedition: New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first people to reach the 8,848.86-metre summit.

Their achievement was a testament to endurance and determination. It was also the crowning glory of the British expedition’s nationalistic motivations on the eve of the young Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

From our vantage in the present, it also represents a high point, not just in climbing terms, but in what we now think of as the modern era of mountaineering. Since then, mountaineering has become massively popular and commercial – with serious implications for the cultures and environments that sustain it.

Scaling the heights

The early mountaineering era began in 1786 when Jaques Balmat and Michel Paccard reached the summit of Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the European Alps at 4,808 metres. From 1854 to 1899 (known as the classic mountaineering period), advances in climbing technology saw ascending peaks by challenging routes become possible and popular.

During the modern era from 1900 to 1963, mountaineers pushed further into the Andes cordillera in South America, explored polar mountains and began high-altitude climbing in Central Asia.

Read more: How Mount Everest helped Britain's post-war bid to burnish global power credentials

Shishapangma, the last of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks to be climbed, was scaled in 1964, marking the start of contemporary mountaineering. Since then, all of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks have been climbed in winter, culminating in the historic winter scaling of the 8,611-metre K2 by a Nepalese expedition in 2021.

The record-setting assault on the world’s 14 highest peaks by Nirmal Puja in 2019 set the stage for a new period of commercial mass mountaineering – involving expectations and conditions that would have stunned the likes of Hillary and Norgay.

Mass mountaineering

The relatively recent influx of what some call novice mountaineers, who may expect luxury packages and a guarantee of summiting, can have dangerous consequences.

Sleeping in heated tents, not preparing their own food or helping to move equipment, does not test mental and physical fitness in such challenging environments. Pushing to the summit may put their own lives, and the lives of other climbers and rescue teams, at risk.

And yet the number of people attempting to climb famous peaks such as Kilimanjaro in Tanzania or Aconcagua in Argentina has increased dramatically. In 2019, there were 878 successful summits on Everest alone.

Read more: Death on Everest: the boom in climbing tourism is dangerous and unsustainable

The days when true mountaineers were looking for new routes and climbing with minimum support have almost disappeared from commercial peaks like Everest. And many of these commercial climbers would not have a chance without professional support.

In 1992, for example, when the first commercial mountaineering expeditions on Everest began, 22 Sherpas and 65 paying mountaineers summited – one Sherpa for three clients. Nowadays, two or even three Sherpas for each member of a commercial expedition is common.

But the romance and achievements of past mountaineers, combined with social media images and an “all-inclusive” adventure tourism industry, can lull inexperienced climbers into a false sense of security. On Everest, this has led to overcrowding, environmental degradation and increased risks for all climbers.

During the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nepal’s Khumbu region – where Everest sits – was effectively shut for climbing. This year, however, some estimate a record of more than 1,000 people could reach the summit.

The next challenge

Experienced mountaineers are responding to the challenges of overcrowding, pollution and socio-cultural impacts on mountain communities by advocating for more responsible and sustainable mountaineering practices.

They want stricter regulations and better training to protect the fragile ecosystems of the Himalayas and other mountain ranges worldwide.

Read more: Is it time to stop climbing mountains? Obsession with reaching summits is a modern invention

This will require many stakeholders to play their part, including governments, mountaineering organisations, tourism operators and local communities. Ultimately, the future of mountaineering depends on preserving these unique mountain environments in the first place.

Finally, maybe it’s time to introduce minimum skill requirements for climbing the world’s highest peak.

As we mark the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest, we need to reflect on the changes that have taken place in mountaineering since. Paradoxically, while it has become more accessible and popular, it has also become more challenging and complex.

Meeting those challenges and solving the problems will be the best way to honour the extraordinary achievement of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.